Like electric lights, water reuse is destined to become a necessity

Indoor toilets were once considered a health hazard. Electric lighting sparked fears of deadly fires. Air conditioning was dismissed as an unnatural threat to human health. It seems absurd now, but each of these technologies—now fundamental to modern buildings—was initially met with widespread skepticism and resistance. Today, we’re seeing history repeat itself with water reuse. As the United States grapples with an escalating water crisis, a powerful solution is gaining momentum. Buildings can intelligently capture, treat, and reuse their own wastewater by leveraging advanced technology, data analytics, and automation to optimize every step of the water reuse process. These smart systems continuously monitor water quality and usage, automatically adjusting treatment processes to ensure safety and efficiency. While current regulations limit this recycled water to non-potable applications, the reality is that water from these systems is often treated to a level that is scientifically safe enough to drink. This isn’t about compromise—it’s about building smarter, managing water as a circular resource, and using it where it’s needed most, all within the building itself. This innovation comes at a critical moment. Nearly 45% of the lower 48 states are currently experiencing drought conditions, with the Southwest and Plains regions particularly hard-hit. Major water systems like the Colorado River and Lake Mead face unprecedented strain, while aquifers supplying 90% of U.S. water systems are depleting at alarming rates. Climate change only compounds these challenges by intensifying evaporation and disrupting weather patterns, leading to both extreme droughts and devastating floods.At the same time, water and sewer rates are skyrocketing as municipalities invest billions to upgrade aging infrastructure and manage dwindling supplies. For buildings, this translates into rising operational costs and growing pressure to adopt more resilient, cost-effective solutions. Against this backdrop, onsite water reuse represents not just an innovative approach but an increasingly necessary one. And predictably, some people may feel uneasy with onsite water reuse, mostly because of perception, unfamiliarity, and the natural human tendency to be cautious about new technologies, especially those involving health and safety. But history shows us that discomfort is often just the first chapter in a story that ends with “How did we ever live without this?” The path from rejection to necessity History keeps repeating itself when it comes to building innovation. Take indoor plumbing—people fought against it tooth and nail in the 1800s. Public health officials, guided by the now-debunked miasma theory—the belief that disease was spread by “bad air” rather than germs—insisted that human waste had to be kept outside the home. Ironically, their reliance on cesspools and open sewers only fueled the spread of deadly diseases like cholera and typhoid, which ravaged entire cities Only as modern sewage systems developed and germ theory took hold did attitudes finally shift. Indoor toilets, once feared as harbingers of disease, gradually became celebrated as symbols of sanitation and progress. Today, their presence is so fundamental that we’ve collectively forgotten they were ever controversial at all. Electric lighting faced similar resistance. Before it lit up our lives, it sparked public panic. Newspapers churned out stories about people getting electrocuted or going blind. The infamous War of the Currents between Thomas Edison and Nikola Tesla only heightened public anxiety, with Edison going so far as to publicly electrocute animals to paint Tesla’s alternating current (AC) as a deadly force. Yet within a generation, those same lights became the very symbol of human advancement. Resistance gave way to adoption, and eventually to total dependence. Then there’s air conditioning. Doctors once warned it would make us soft and sickly. In the early 1950s, the National Association of Home Builders and the University of Texas partnered to create the Austin Air-Conditioned Village—a real neighborhood built to study how everyday families would adapt to living with air conditioning. Six homes were equipped with A/C, while others were left uncooled. Researchers tracked not just energy usage, but human behavior, comfort, and social response. Some participants worried about health effects, while others complained that the cooled air attracted scorpions and other desert pests. But over time, skepticism gave way to comfort, and the experiment helped lay the groundwork for widespread adoption. Now more than 90% of American homes have A/C, and places like Phoenix or Miami would lose millions of residents without it. What was once considered risky has become absolutely essential. Water reuse is gaining popularity Our centralized water infrastructure is showing its age. Pipes laid a century ago are failing. Treatment plants design

Indoor toilets were once considered a health hazard. Electric lighting sparked fears of deadly fires. Air conditioning was dismissed as an unnatural threat to human health. It seems absurd now, but each of these technologies—now fundamental to modern buildings—was initially met with widespread skepticism and resistance.

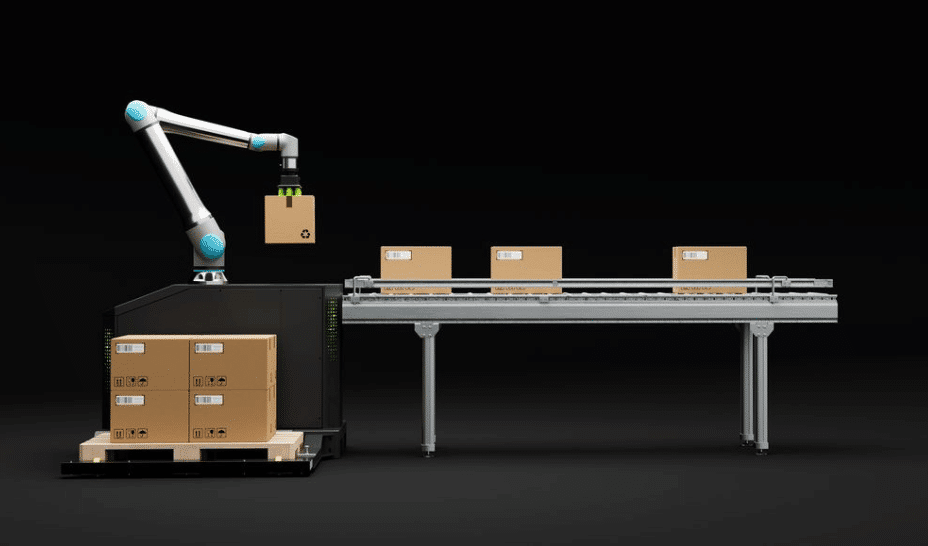

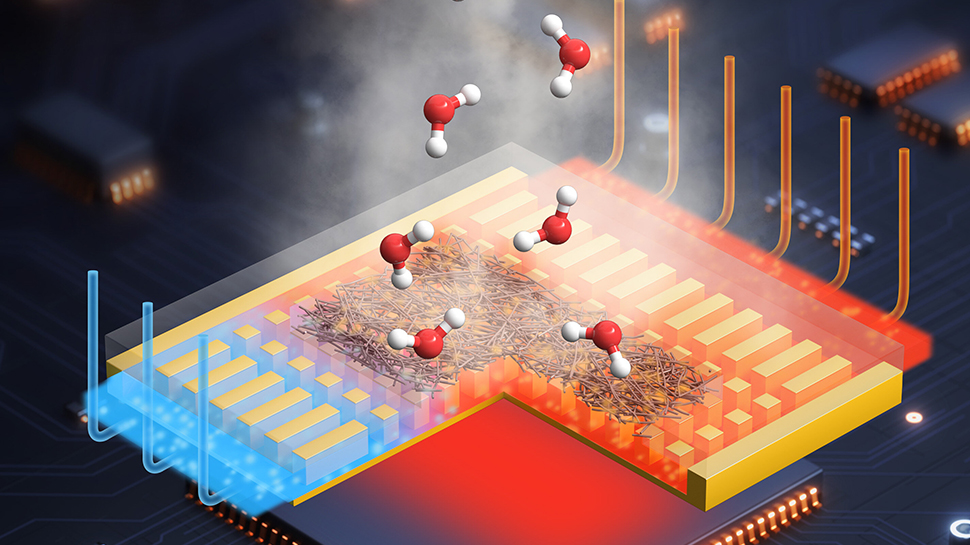

Today, we’re seeing history repeat itself with water reuse. As the United States grapples with an escalating water crisis, a powerful solution is gaining momentum. Buildings can intelligently capture, treat, and reuse their own wastewater by leveraging advanced technology, data analytics, and automation to optimize every step of the water reuse process. These smart systems continuously monitor water quality and usage, automatically adjusting treatment processes to ensure safety and efficiency. While current regulations limit this recycled water to non-potable applications, the reality is that water from these systems is often treated to a level that is scientifically safe enough to drink. This isn’t about compromise—it’s about building smarter, managing water as a circular resource, and using it where it’s needed most, all within the building itself.

This innovation comes at a critical moment. Nearly 45% of the lower 48 states are currently experiencing drought conditions, with the Southwest and Plains regions particularly hard-hit. Major water systems like the Colorado River and Lake Mead face unprecedented strain, while aquifers supplying 90% of U.S. water systems are depleting at alarming rates. Climate change only compounds these challenges by intensifying evaporation and disrupting weather patterns, leading to both extreme droughts and devastating floods.

At the same time, water and sewer rates are skyrocketing as municipalities invest billions to upgrade aging infrastructure and manage dwindling supplies. For buildings, this translates into rising operational costs and growing pressure to adopt more resilient, cost-effective solutions.

Against this backdrop, onsite water reuse represents not just an innovative approach but an increasingly necessary one. And predictably, some people may feel uneasy with onsite water reuse, mostly because of perception, unfamiliarity, and the natural human tendency to be cautious about new technologies, especially those involving health and safety. But history shows us that discomfort is often just the first chapter in a story that ends with “How did we ever live without this?”

The path from rejection to necessity

History keeps repeating itself when it comes to building innovation. Take indoor plumbing—people fought against it tooth and nail in the 1800s. Public health officials, guided by the now-debunked miasma theory—the belief that disease was spread by “bad air” rather than germs—insisted that human waste had to be kept outside the home. Ironically, their reliance on cesspools and open sewers only fueled the spread of deadly diseases like cholera and typhoid, which ravaged entire cities

Only as modern sewage systems developed and germ theory took hold did attitudes finally shift. Indoor toilets, once feared as harbingers of disease, gradually became celebrated as symbols of sanitation and progress. Today, their presence is so fundamental that we’ve collectively forgotten they were ever controversial at all.

Electric lighting faced similar resistance. Before it lit up our lives, it sparked public panic. Newspapers churned out stories about people getting electrocuted or going blind. The infamous War of the Currents between Thomas Edison and Nikola Tesla only heightened public anxiety, with Edison going so far as to publicly electrocute animals to paint Tesla’s alternating current (AC) as a deadly force. Yet within a generation, those same lights became the very symbol of human advancement. Resistance gave way to adoption, and eventually to total dependence.

Then there’s air conditioning. Doctors once warned it would make us soft and sickly. In the early 1950s, the National Association of Home Builders and the University of Texas partnered to create the Austin Air-Conditioned Village—a real neighborhood built to study how everyday families would adapt to living with air conditioning. Six homes were equipped with A/C, while others were left uncooled. Researchers tracked not just energy usage, but human behavior, comfort, and social response. Some participants worried about health effects, while others complained that the cooled air attracted scorpions and other desert pests. But over time, skepticism gave way to comfort, and the experiment helped lay the groundwork for widespread adoption. Now more than 90% of American homes have A/C, and places like Phoenix or Miami would lose millions of residents without it. What was once considered risky has become absolutely essential.

Water reuse is gaining popularity

Our centralized water infrastructure is showing its age. Pipes laid a century ago are failing. Treatment plants designed for consistent climate patterns are buckling under the pressure of intensifying droughts, floods, and wildfires. Meanwhile, commercial and residential buildings account for the majority of urban water use—yet a significant portion of that demand is for non-potable applications like toilet flushing, irrigation, and cooling, which don’t require pristine drinking water quality.

Onsite water reuse offers a compelling alternative. With today’s technology, buildings and industry can recycle up to 95% of their wastewater. This approach strengthens sustainability, enhances resilience, and increasingly improves the bottom line. San Francisco has already made water reuse mandatory for larger developments. Other cities such as Los Angeles and Austin are creating incentives or updating building codes. Forward-thinking developers aren’t waiting for mandates; they’re embracing water reuse to meet sustainability commitments and future-proof their investments.

Still, old habits and perceptions persist. Some people instinctively recoil at the idea of treated wastewater, even when it’s used exclusively for non-potable purposes. But both the data and the historical pattern are clear about where we’re headed.

The lifecycle of transformative technology

Every transformative building technology follows a predictable journey:

- First comes resistance: “You want me to put what inside my building?”

- Then adoption: “Actually, this solves a real problem quite elegantly.”

- Followed by mandates and markets: “New code requires it, and buyers expect it.”

- Finally, normalization: “Remember when buildings didn’t have this?”

Onsite water reuse is already transitioning from the second to the third phase—and picking up speed. Soon enough, we’ll look back at the practice of flushing toilets with drinking water with the same bewilderment we now feel about houses without indoor plumbing. The real question isn’t whether onsite water reuse will become standard practice. It’s how quickly we can make the leap from outrageous to obvious.

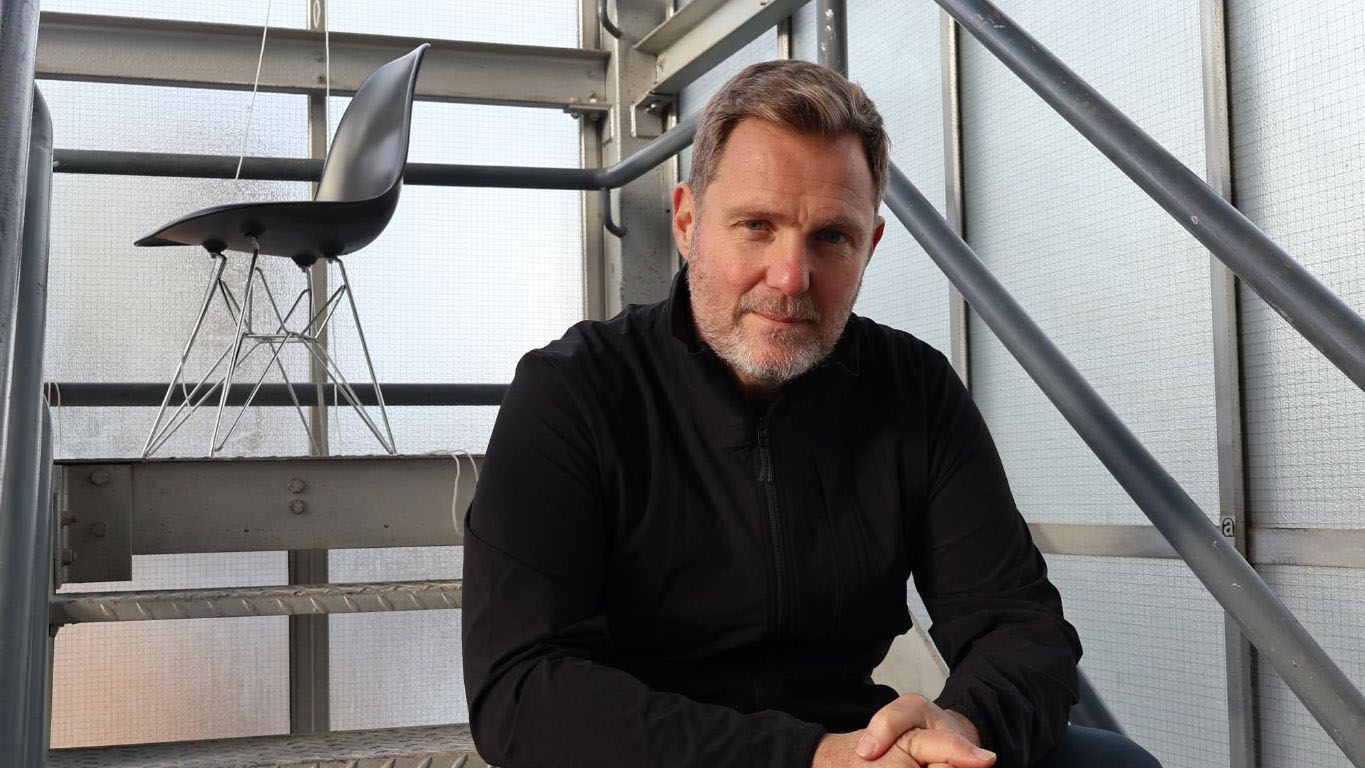

Aaron Tartakovsky is the CEO and co-founder of Epic Cleantec.

![What Is a Markup Language? [+ 7 Examples]](https://static.semrush.com/blog/uploads/media/82/c8/82c85ebca40c95d539cf4b766c9b98f8/markup-language-sm.png)