Why Deserts Get So Cold at Night?

Deserts aren’t just hot—they’re thermally extreme landscapes where physics, biology, and climate intersect. Discover why these sun-scorched places turn icy cold at night, how life adapts to survive, and what rising global temperatures mean for their delicate balance. Ready to rethink everything you

When you think of deserts, chances are you imagine unbearable heat—sun-scorched sand, blinding light, and camels trudging under a ruthless sky. But here's a twist: many deserts get freezing cold at night. And not just "bring a jacket" cold—more like "bundle up or you’re shivering by midnight" cold. In fact, temperatures in some deserts can drop by over 40–60°F (20–30°C) in just a few hours after sunset. How does a place go from frying eggs to freezing toes in one day?

To understand this thermal whiplash, we need to unpack the science of what makes deserts so extreme—and why this ancient pattern is now shifting in an era of climate change.

Not Just Hot—Deserts are Defined by Dryness

Contrary to popular belief, deserts aren't defined by heat, but by lack of moisture. Any region that receives less than 10 inches (250 mm) of rainfall annually qualifies as a desert. That means Antarctica and Greenland, both frigid, are technically deserts too. The common denominator? Low humidity in the air and soil. And here lies our first clue—moisture is incredibly good at holding heat.

In places with high humidity, water vapor acts like a thermal blanket. It absorbs heat during the day and releases it slowly at night. In deserts, where the air is bone-dry and the skies are clear, there’s no such buffer. So when the sun disappears, the heat escapes almost instantly.

The Daytime Heat: Direct, Intense, and Fleeting

During the day, deserts are exposed to intense solar radiation. With little to no cloud cover and minimal water vapor, sunlight slams into the surface unfiltered. Sand and rock heat up quickly under these conditions, often sending ground temperatures soaring to 120°F (49°C) or more. But sand has a hidden flaw—it’s a terrible heat reservoir. It heats up fast but also loses heat just as quickly.

So while desert afternoons are blisteringly hot, the warmth doesn't linger. The moment the sun drops below the horizon, the heat party is over.

The Nighttime Crash: Where Does the Heat Go?

The rapid cooling of deserts after sunset is a phenomenon known as radiative cooling. Without clouds or atmospheric moisture to trap outgoing heat, infrared radiation escapes directly into space. In a matter of hours, desert temperatures can plummet—sometimes to freezing levels.

Take the Sahara Desert, for example. Daytime highs can exceed 100°F (38°C), but nighttime lows in winter can approach or fall below 32°F (0°C). In Chile’s Atacama Desert, which sits at high altitude and is one of the driest places on Earth, nights regularly drop below freezing. Even the Mojave Desert in the U.S. is known for its thermal mood swings—sweaty afternoons followed by hoodie-weather evenings.

Adapt or Freeze: How Life Survives

Desert wildlife are champions of thermal regulation. Nocturnal mammals like jerboas hide in underground burrows that retain heat from the day. Reptiles like sidewinder snakes use the sand as insulation, curling beneath the surface to stay warm. Scorpions lower their metabolic rate to conserve energy, while desert beetles use their unique body shapes to minimize moisture loss and heat transfer.

Even larger animals like desert foxes and hares use their large ears as radiators during the day and retreat to dens at night. For desert life, adaptability isn’t optional—it’s survival.

Plants, too, have evolved clever strategies. Succulents like cacti store water in thick tissues that not only hydrate them during droughts but also serve as thermal batteries—absorbing warmth during the day and releasing it slowly at night. Others are coated in wax or fine hairs, creating a thin insulating layer that buffers them from extreme cold.

What Humans have Learned from the Desert

Long before air conditioning, desert-dwelling communities developed ingenious survival techniques. Nomadic tents, built with layered cloth and wool, offered daytime ventilation and nighttime insulation. Adobe houses, common in arid regions, absorb heat during the day and release it at night—regulating interior temperatures naturally.

Even modern architecture in cities like Phoenix or Dubai draws from this ancient wisdom. Builders use materials with thermal mass, install reflective coatings, and implement passive solar design. Smart windows, insulation tech, and temperature-sensitive glass are 2025’s answers to a challenge nature has long mastered.

Climate Change is Disrupting Desert Nights

Today, the balance of desert heat is shifting. Climate change is making desert nights warmer than before, thanks to an increase in greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane that trap more heat in the atmosphere. This interrupts the delicate thermal rhythm deserts have followed for millennia.

Some desert plants need cool nights to flower. Certain animals rely on nighttime chill for mating or metabolic triggers. Without those drops in temperature, entire ecosystems may lose their balance. Add urban sprawl and artificial lighting, and we get the urban heat island effect—where cities remain unnaturally warm after dark, reshaping life for everything from lizards to lichens.

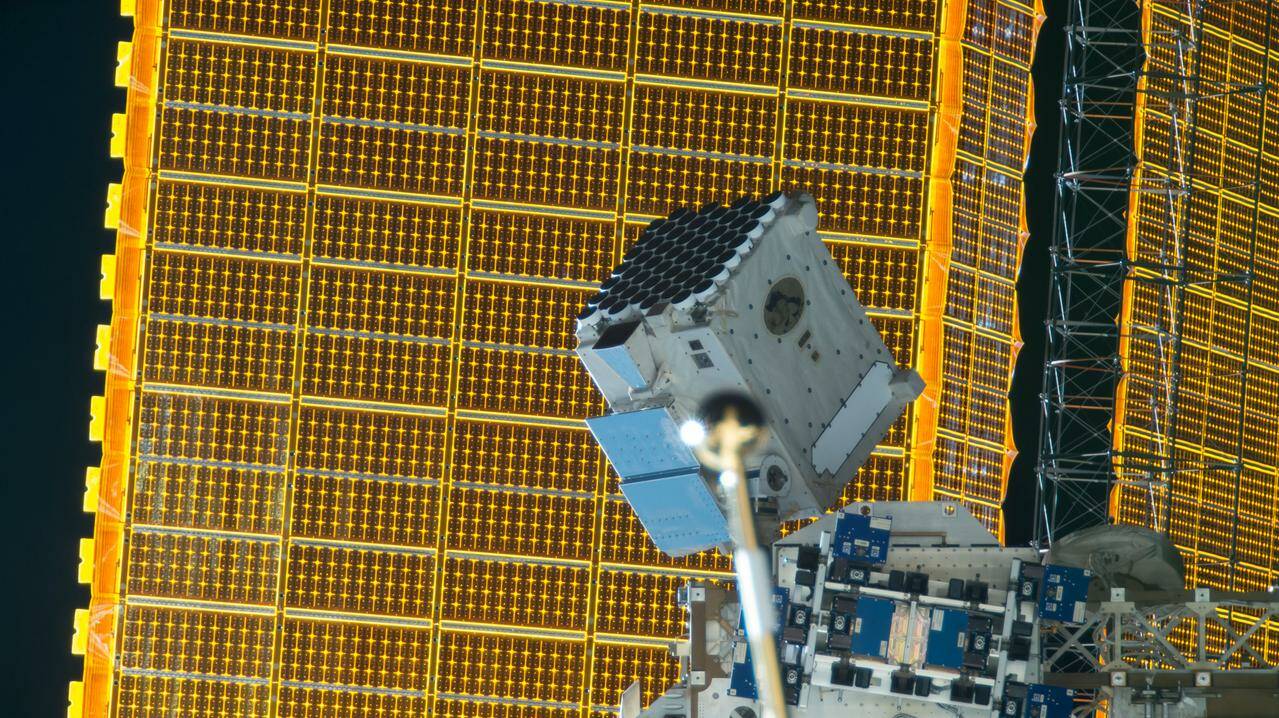

Martian Connection: Space-age Deserts

Interestingly, deserts on Earth serve as test grounds for space exploration. Mars, with its thin atmosphere and desert-like terrain, mimics these conditions. Temperatures on the Red Planet swing from 70°F (21°C) during the day to −100°F (−73°C) at night. NASA often tests its rovers and habitat concepts in extreme Earth deserts like the Atacama, preparing for future missions.

In many ways, Earth’s deserts aren’t just extreme—they’re otherworldly.

When the sun sets in the desert, the transformation is almost cinematic. The heat lifts, the stars burst through the sky, and a deep silence takes hold. Creatures emerge, winds whisper across the dunes, and the whole landscape seems to breathe differently. The chill doesn’t just change the air—it changes the mood.

So next time you picture a desert, don’t just imagine the searing sun. Think also of frost-tipped dunes, survival strategies written in biology, and a fragile balance between fire and ice. In every way, deserts are cosmic mood rings—absorbing the day, releasing it at night, and teaching us lessons about resilience, adaptation, and the quiet power of contrast.

![Snapchat Shares Trend Insights for Marketers To Tap Into This Summer [Infographic]](https://imgproxy.divecdn.com/7LB56F586EcY82vl5r47Ba6f7RdKcHkNelnSgSe8Umc/g:ce/rs:fit:770:435/Z3M6Ly9kaXZlc2l0ZS1zdG9yYWdlL2RpdmVpbWFnZS9zbmFwX2tzYTIucG5n.webp)

![What Is a Markup Language? [+ 7 Examples]](https://static.semrush.com/blog/uploads/media/82/c8/82c85ebca40c95d539cf4b766c9b98f8/markup-language-sm.png)