It’s officially summer, and the grid is stressed

It’s crunch time for the grid this week. As I’m writing this newsletter, it’s 100 °F (nearly 38 °C) here in New Jersey, and I’m huddled in the smallest room in my apartment with the shades drawn and a single window air conditioner working overtime. Large swaths of the US have seen brutal heat this…

It’s crunch time for the grid this week. As I’m writing this newsletter, it’s 100 °F (nearly 38 °C) here in New Jersey, and I’m huddled in the smallest room in my apartment with the shades drawn and a single window air conditioner working overtime.

Large swaths of the US have seen brutal heat this week, with multiple days in a row nearing or exceeding record-breaking temperatures. Spain recently went through a dramatic heat wave too, as did the UK, which is unfortunately bracing for another one soon. As I’ve been trying to stay cool, I’ve had my eyes on a website tracking electricity demand, which is also hitting record highs.

We rely on electricity to keep ourselves comfortable, and more to the point, safe. These are the moments we design the grid for: when need is at its very highest. The key to keeping everything running smoothly during these times might be just a little bit of flexibility.

While heat waves happen all over the world, let’s take my local grid as an example. I’m one of the roughly 65 million people covered by PJM Interconnection, the largest grid operator in the US. PJM covers Virginia, West Virginia, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey, as well as bits of a couple of neighboring states.

Earlier this year, PJM forecast that electricity demand would peak at 154 gigawatts (GW) this summer. On Monday, just a few days past the official start of the season, the grid blew past that, averaging over 160 GW between 5 p.m. and 6 p.m.

The fact that we’ve already passed both last year’s peak and this year’s forecasted one isn’t necessarily a disaster (PJM says the system’s total capacity is over 179 GW this year). But it is a good reason to be a little nervous. Usually, PJM sees its peak in July or August. As a reminder, it’s June. So we shouldn’t be surprised if we see electricity demand creep to even higher levels later in the summer.

It’s not just PJM, either. MISO, the grid that covers most of the Midwest and part of the US South, put out a notice that it expected to be close to its peak demand this week. And the US Department of Energy released an emergency order for parts of the Southeast, which allows the local utility to boost generation and skirt air pollution limits while demand is high.

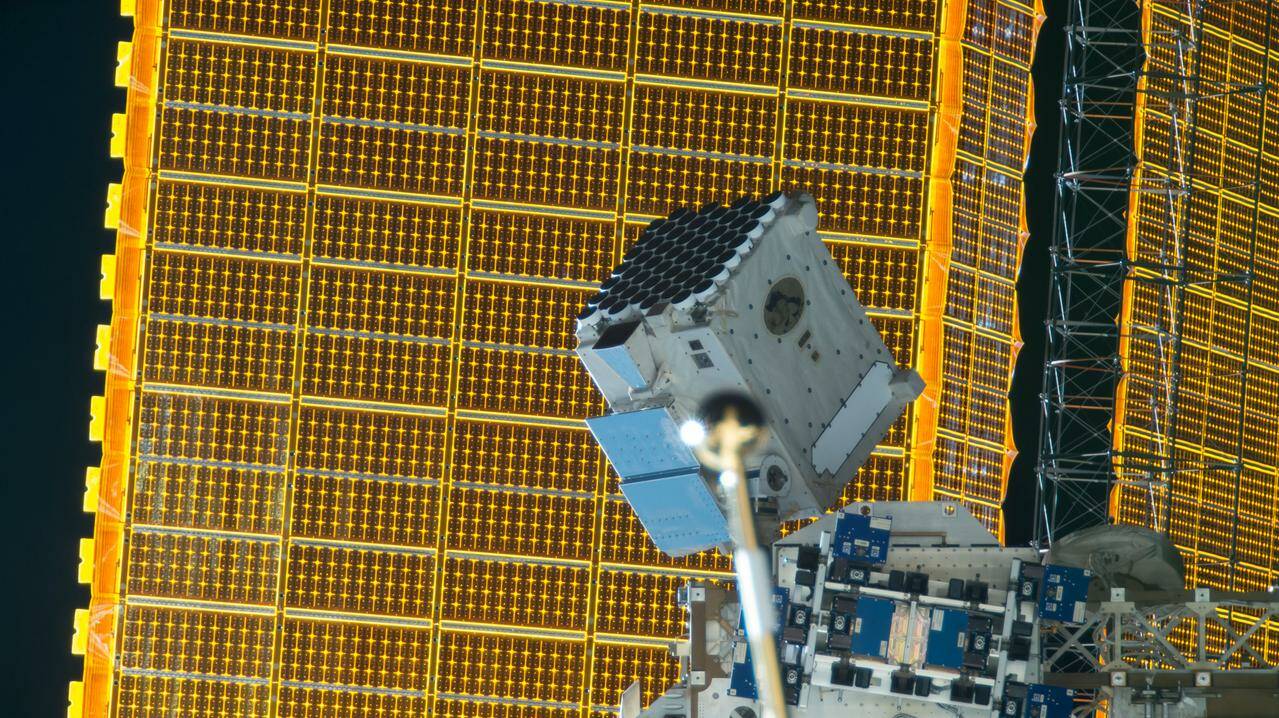

This pattern of maxing out the grid is only going to continue. That’s because climate change is pushing temperatures higher, and electricity demand is simultaneously swelling (in part because of data centers like those that power AI). PJM’s forecasts show that the summer peak in 2035 could reach nearly 210 GW, well beyond the 179 GW it can provide today.

Of course, we need more power plants to be built and connected to the grid in the coming years (at least if we don’t want to keep ancient, inefficient, expensive coal plants running, as we covered last week). But there’s a quiet strategy that could limit the new construction needed: flexibility.

The power grid has to be built for moments of the absolute highest demand we can predict, like this heat wave. But most of the time, a decent chunk of capacity that exists to get us through these peaks sits idle—it only has to come online when demand surges. Another way to look at that, however, is that by shaving off demand during the peak, we can reduce the total infrastructure required to run the grid.

If you live somewhere that’s seen a demand crunch during a heat wave, you might have gotten an email from your utility asking you to hold off on running the dishwasher in the early evening or to set your air conditioner a few degrees higher. These are called demand response programs. Some utilities run more organized programs, where utilities pay customers to ramp down their usage during periods of peak demand.

PJM’s demand response programs add up to almost eight gigawatts of power—enough to power over 6 million homes. With these programs, PJM basically avoids having to fire up the equivalent of multiple massive nuclear power plants. (It did activate these programs on Monday afternoon during the hottest part of the day.)

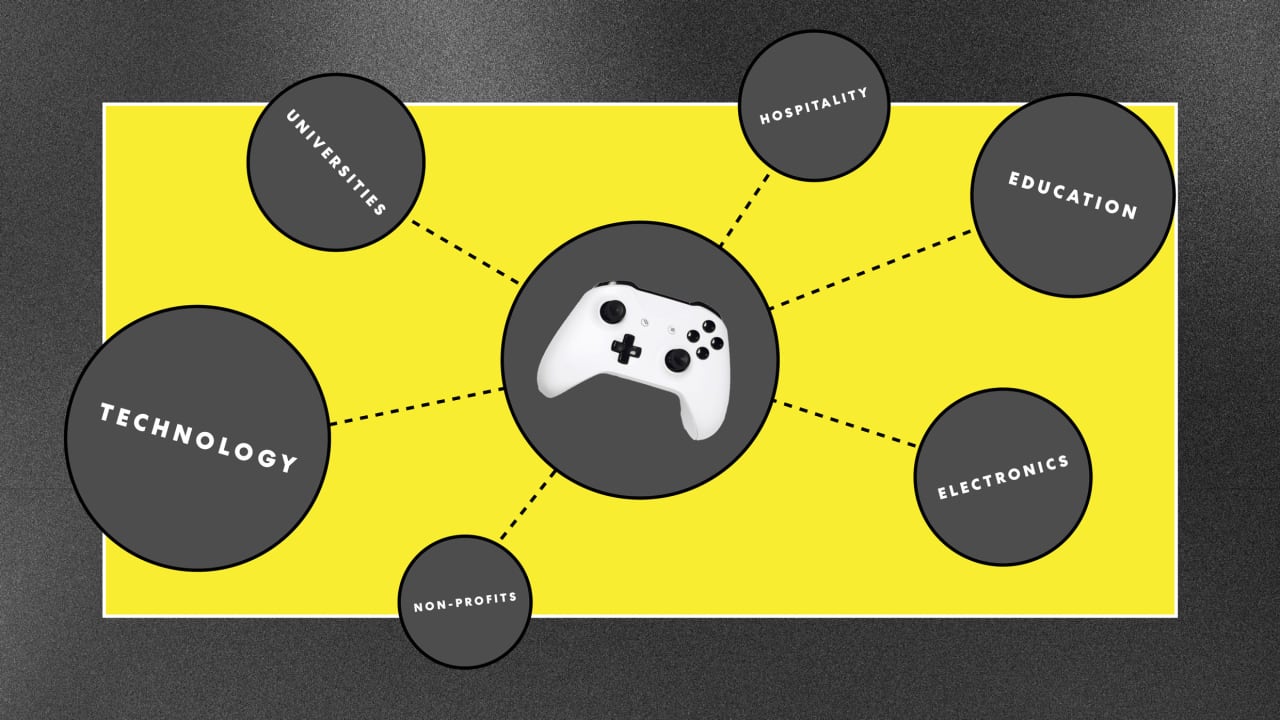

As electricity demand goes up, building in and automating this sort of flexibility could go a long way to reducing the amount of new generation needed. One report published earlier this year found that if data centers agreed to have their power curtailed for just 0.5% of the time (around 40 hours out of a year of continuous operation), the grid could handle about 18 GW of new power demand in the PJM region without adding generation capacity.

For the whole US, this level of flexibility would allow the grid to take on an additional 98 gigawatts of new demand without building any new power plants to meet it. To give you a sense of just how significant that would be, all the nuclear reactors in the US add up to 97 gigawatts of capacity.

Tweaking the thermostat and ramping down data centers during hot summer days won’t solve the demand crunch on their own, but it certainly won’t hurt to have more flexibility.

This article is from The Spark, MIT Technology Review’s weekly climate newsletter. To receive it in your inbox every Wednesday, sign up here.

![Snapchat Shares Trend Insights for Marketers To Tap Into This Summer [Infographic]](https://imgproxy.divecdn.com/7LB56F586EcY82vl5r47Ba6f7RdKcHkNelnSgSe8Umc/g:ce/rs:fit:770:435/Z3M6Ly9kaXZlc2l0ZS1zdG9yYWdlL2RpdmVpbWFnZS9zbmFwX2tzYTIucG5n.webp)

![What Is a Markup Language? [+ 7 Examples]](https://static.semrush.com/blog/uploads/media/82/c8/82c85ebca40c95d539cf4b766c9b98f8/markup-language-sm.png)