Banking on AI: Firms such as BNY balance high risk with the potential for transformative tech

Every Wall Street bank is looking for an edge in this cutthroat sector. Can AI deliver?

In early 2023, soon after OpenAI released ChatGPT to the world, BNY gathered its senior executives to decide how to incorporate artificial intelligence into its financial empire.

While AI has created an arms race across sectors from health care to law firms, banks like BNY still have to proceed with caution. A rogue agent or hallucination could trigger the next financial meltdown, after all, and that’s not to mention the reams of red tape and regulations that institutions have to consider when it comes to sensitive data and customers’ personally identifiable information.

Still, the BNY executives recognized that AI could be one of the most significant technological developments in the company’s history, and they didn’t want to miss the boat. Originally founded as the Bank of New York in 1784 by Alexander Hamilton, BNY is the oldest bank in the country. And as Sarthak Pattanaik, whom the bank chose to lead its artificial intelligence efforts a few months later, put it to Fortune: “You don’t get to 240 years without being innovative.”

BNY moved quickly to fold AI into its infrastructure, launching a tool last year called Eliza, named after Hamilton’s wife, which is powered by existing models including OpenAI’s GPT-4 and Google’s Gemini. Eliza allows employees to build AI agents such as chatbots that offer niche subject matter expertise on areas like compliance, as well as more advanced reasoning tasks. And just a few months ago, BNY announced a new partnership with OpenAI that will see the two institutions collaborate on financial services use cases.

New AI leaders at the country’s leading financial institutions, like Pattanaik, have had to weigh whether to develop products themselves rather than seek outside vendors—moving carefully while looking over their shoulders in the famously competitive and cutthroat sector.

The norm for banks has long been to build new technology in-house. Goldman Sachs even built its own proprietary email client. But that approach is shifting, says David Haber, a veteran of both fintech startups and Goldman Sachs who now works as a general partner at Andreessen Horowitz. “The culture was, if it wasn’t built here, we’re not interested,” he recalls. “The past five or six years, the culture really has, in my opinion, begun changing pretty dramatically.” Some banks, like BNY, are training their own open-source systems, relying on base models built by the likes of Meta or Mistral as a starting point and training them on their own data, as well as turning to proprietary models such as those from OpenAI for some use cases.

The cloud revolution, when financial institutions began partnering with third-party providers like Amazon Web Services during the 2010s, helped spur the transition. “There’s a recognition that they’re better served, frankly, adopting the best-of-breed technology,” Haber tells Fortune. “I suspect AI is only going to accelerate that trend.”

Banks are no strangers to artificial intelligence, having used machine learning for decades to analyze consumer behavior and perform core functions like underwriting. But David Griffiths, the chief technology officer at Citi, tells Fortune that the generative AI models championed by companies like OpenAI and Anthropic have disrupted much of the classical machine learning that banks previously worked with data scientists and researchers to develop.

Where machine learning would be designed for specific use cases, like fraud modeling or document recognition, large language models can be trained for a wider variety of tasks. “It actually can be a great simplifying force for us in certain areas, because we can get rid of these bespoke technologies and solutions and vendors and use something that’s more general purpose,” Griffiths says.

Banks have mostly looked outside their walls for help when it comes to those models: the massive AI systems developed by deep-pocketed companies like OpenAI and trained with trillions of data points. “We want to be able to work as closely as we can with the model providers themselves, because the technology is so new, and we want to be able to give feedback,” Griffiths says.

While BNY publicly announced its partnership with OpenAI, Pattanaik says that the bank works with all three proprietary models—Anthropic, Google’s Gemini, and OpenAI—as well as open-source options including Meta’s Llama models and Mistral, which the bank manages on premises for security purposes. He declined to go into specifics on how BNY’s partnership with OpenAI deviates from its relationship with the other companies, saying that the two companies are working more closely together on “intellectual capital sharing” rather than just paying for computing resources.

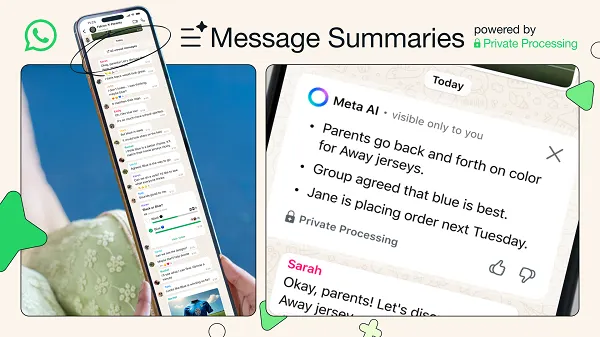

Many banks have developed their own virtual assistants, like BNY’s Eliza, as well as Citi Assist, which the company rolled out to around 150,000 employees at the end of last year. As suggested by the tool’s name, Griffiths says that AI mostly serves an assistive purpose right now, making staffers more “productive” by helping with coding or answering procedural questions about the bank’s bureaucracy. “As the agentic model becomes real and unfolds, that’s going to be interesting to see how that might change the shape of the workforce,” Griffiths says. “The next six to 12 months are going to be really telling across the industry.”

AI agents, which describe AI systems that can take actions on their own rather than simply suggesting actions to people or generating text or images, also create increased risk and potential problems, such as hallucination. All generative AI models potentially suffer from “hallucinations”—where the AI model confidently provides inaccurate outputs—but if those inaccuracies now lead to financial transactions, the consequences could be far more severe. Griffiths says that quality controls like fine-tuning the models and providing them with specific data can help reduce the likelihood of confabulation.

The presence of sensitive information across finance creates natural limits on the types of use cases that banks pursue—at least for now. Because BNY mostly operates in the institutional space, meaning it doesn’t hold consumer data like credit card or mortgage information, it has more freedom than most competitors. Even so, Pattanaik says that BNY tries to avoid training models with personal information. If it does, the bank uses a “walled garden” approach that goes through encryption and red team testing that simulates cyberattacks.

Banks are also taking a more vigilant approach when looking beyond the LLM developers and buying other types of AI software, says Lindsay Fitzgerald, a former banker at Morgan Stanley who then led American Express’s corporate venture arm before starting her own firm, Vesey Ventures. Fitzgerald, who counts major banks as backers, says that many banks have built a separate, more cumbersome procurement process for buying third-party AI tools. “There’s a flag for, does this use AI?” she tells Fortune. “If you hit that flag, you’re signing up for a couple extra weeks of onboarding.”

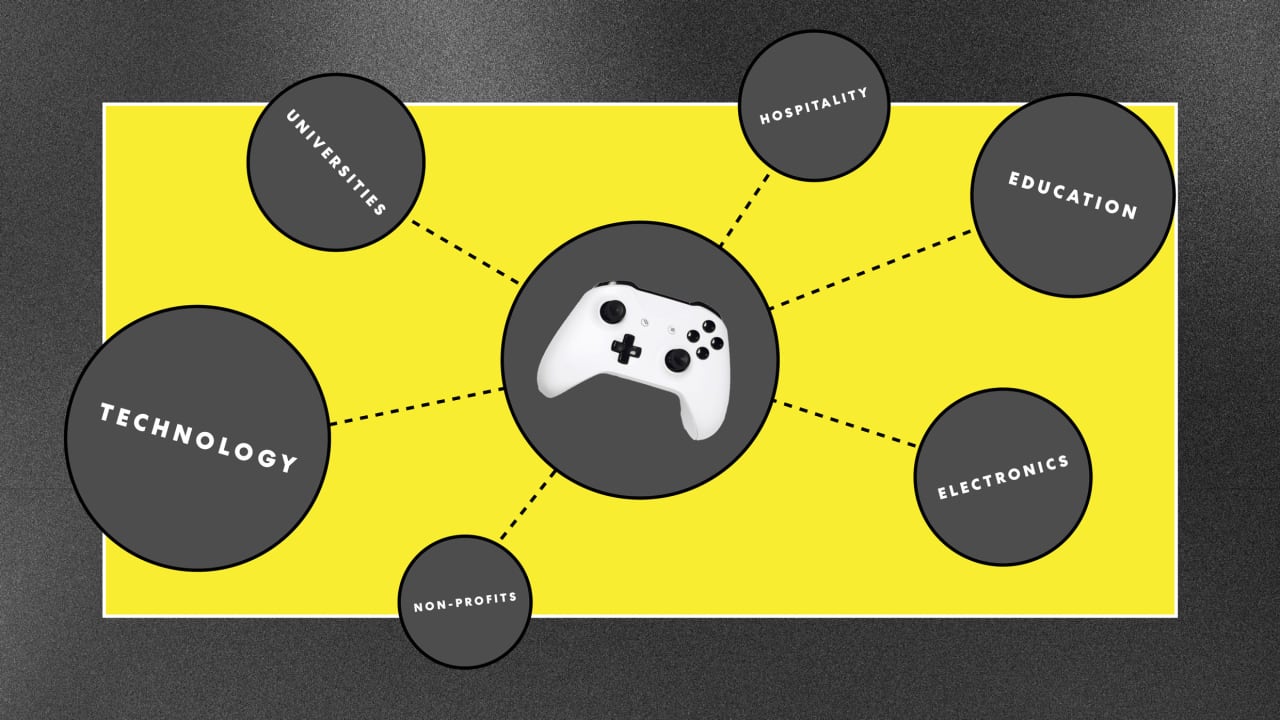

As a result, banks tend to buy software that doesn’t touch their core infrastructure. Fitzgerald highlighted one portfolio company, Stuut, which helps collect accounts receivable through AI, including voice agents. “It’s an extremely low-risk implementation of AI,” she says, because it does not touch customers’ personal information. That application layer of startups catering to financial institutions is only likely to grow.

In just a few short years since the launch of ChatGPT, AI has already changed banking. According to a 2024 report from the research and analytics platform Evident Insights that ranked the major global banks by AI adoption, all 50 that the firm analyzed referenced AI in at least one investor relations document. Over half publicly report on use cases in production. The leading bank in the rankings, JPMorgan Chase, announced at a conference in September that it valued AI use cases within the bank at around $2 billion.

Griffiths says that Citi, which Evident ranked eighth, is aware of the competitive pressure, though the bank tries to focus on using AI to either make or save money. “We’re trying to avoid just being reactive to what we read or hear about what other people are doing,” he says. “We’ve got very clear plans for the next year or so with this—but of course, who knows what the models are going to be capable of in six months.”

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com

![Snapchat Shares Trend Insights for Marketers To Tap Into This Summer [Infographic]](https://imgproxy.divecdn.com/7LB56F586EcY82vl5r47Ba6f7RdKcHkNelnSgSe8Umc/g:ce/rs:fit:770:435/Z3M6Ly9kaXZlc2l0ZS1zdG9yYWdlL2RpdmVpbWFnZS9zbmFwX2tzYTIucG5n.webp)

![What Is a Markup Language? [+ 7 Examples]](https://static.semrush.com/blog/uploads/media/82/c8/82c85ebca40c95d539cf4b766c9b98f8/markup-language-sm.png)