Aurora hits a self-driving trucking milestone. But the road ahead is still bumpy

Self-driving vehicle startups have often drawn skepticism for overpromising and underdelivering—see: Argo AI and GM’s Cruise subsidiary, both now in corporate junkyards—but in early May, one of them achieved a milestone that had long eluded the industry: delivering a truckload of cargo for a paying customer on public roads—with no human behind the wheel. Aurora’s May 1 announcement that it had begun commercial deliveries for its first customers, Hirschbach Motor Lines and Uber Freight, on two autonomous semitrailer trucks between Dallas and Houston followed some eight years of work by the Pittsburgh-based firm. Aurora reached that milestone about half a year later than it had planned last year, owing to extra time needed to complete its “safety case” testing and self-certification. “This is a multiyear journey,” says Aurora president Ossa Fisher. “A few months seemed minuscule in the grand scheme of both the opportunity that lies ahead of us and what came before.” But barely two weeks after the announcement, the company was back to having safety operators sitting behind the wheels of the two trucks. In a May 16 company blog post, CEO and chairman Chris Urmson said one of its truck-manufacturing partners, Paccar, had requested that change “because of certain prototype parts in their base vehicle platform.” He wrote that “after much consideration,” Aurora “respected their request and are moving the observer, who had been riding in the back of some of our trips, from the back seat to the front seat.” [Photo: Aurora] The International Brotherhood of Teamsters, the union that represents drivers, would prefer to keep things that way—and has been lobbying lawmakers in such states as Texas, California, and Massachusetts to codify that in regulations. “Our position is that all trucks should have human operator requirements,” says Teamsters spokesman Matt McQuaid. A long road ahead Despite the upshift-downshift progress, however, Aurora is still farther down the road than other companies in this space. Gartner analyst Jonathan Davenport rates the company as “significantly ahead” of such competitors as Plus AI, which plans to inaugurate commercial service in 2027 and in early June announced plans for an initial public offering (its second attempt to do so). Aurora staged its IPO in 2021, which has allowed a much clearer view of its financials than what’s available from the likes of another company to make self-driving vehicles a commercial reality: Waymo. And those numbers show that running an autonomous-trucking company isn’t cheap: In the first quarter of 2025, Aurora reported a net loss of $208 million. On its Q1 earnings call in May, company executives predicted $175 million to $185 million in quarterly expenses and revenue in “the mid-single digits” over the rest of 2025. “There’s a big difference between the operating cost today and the operating cost at scale,” Fisher tells Fast Company. “We are not making money on a per load basis today, and that’s public information.” Aurora’s plans include not just scaling up its fleet but also upgrading its hardware—for instance, deploying a more compact version of its FirstLight Lidar sensor. Shrinking the sensing equipment could also help Aurora move closer to its goal of bringing its self-driving technology to passenger cars. Chirs Urmson, CEO [Photo: Aurora] “We’ll have a next-generation of trucks in a year,” she says. “We’ll go to tens of trucks and hundreds of trucks and thousands of trucks. And as we reach scale, that’s when you get the performance metrics to be highly profitable.” Davenport says the plan is indeed feasible, but has some doubts about the timeline. “We’re still going to be two or three years, probably,” he says. “I would still classify it as probably in the development stage of R&D.” Aurora and other firms in the sector benefit from a market problem that needs solving: Traditional trucking companies can’t hire enough drivers to meet demand. But even then, Gartner forecasts that autonomous trucks will make up under 5% of truck fleets worldwide by 2029. Either snow or rain or gloom of night In the nearer term, Aurora aims to expand its “operating design domain”—the conditions under which its trucks can roll—beyond the current requirement of clear daylight. “If there’s rain in the forecast, some days we don’t launch,” Fisher says. “We’re working very rapidly to resolve any and all weather issues and see that happening later this year.” Here, Aurora is following a common route for autonomous-vehicle projects: Start operations in ideal weather, then drive in increasingly less pleasant conditions. Waymo, for example, inaugurated service in sunny Phoenix, but when it opens for business in Washington sometime in 2026 its robotaxis will have to deal with a full spectrum of seasonal weather that, in the case of the occasional blizzard, should keep human drivers off the roads. Unlocking commerci

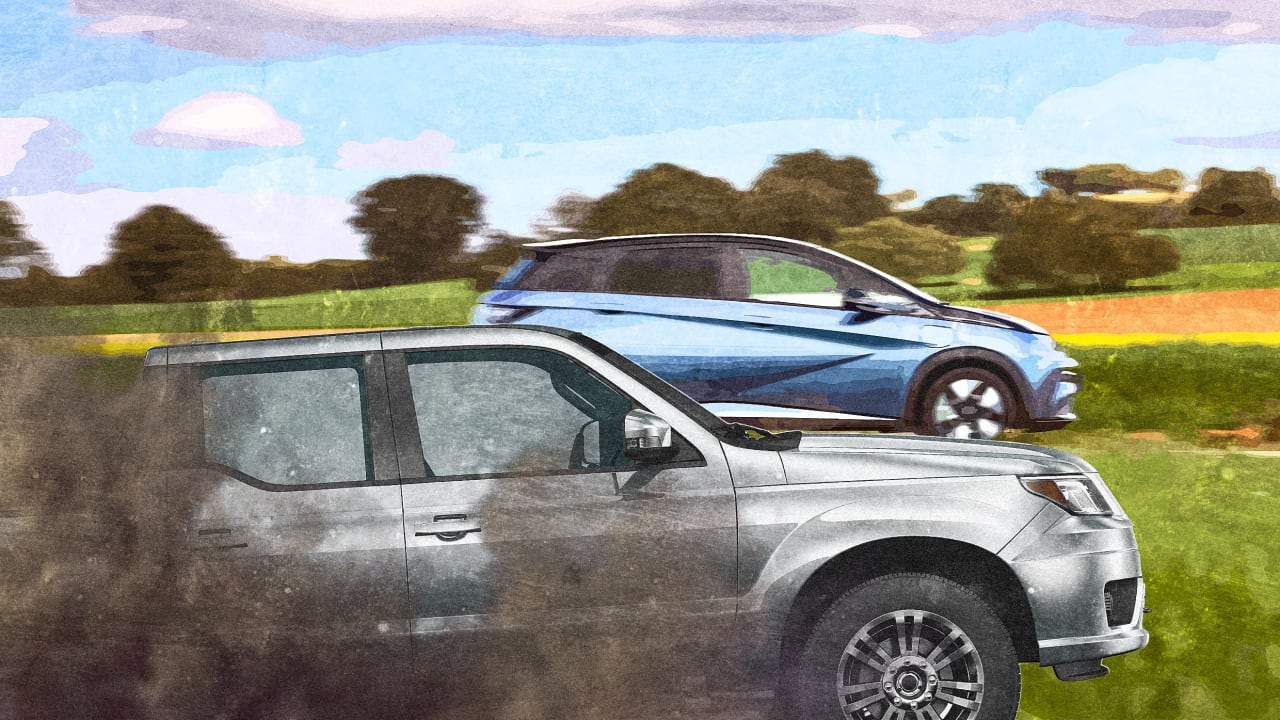

Self-driving vehicle startups have often drawn skepticism for overpromising and underdelivering—see: Argo AI and GM’s Cruise subsidiary, both now in corporate junkyards—but in early May, one of them achieved a milestone that had long eluded the industry: delivering a truckload of cargo for a paying customer on public roads—with no human behind the wheel.

Aurora’s May 1 announcement that it had begun commercial deliveries for its first customers, Hirschbach Motor Lines and Uber Freight, on two autonomous semitrailer trucks between Dallas and Houston followed some eight years of work by the Pittsburgh-based firm.

Aurora reached that milestone about half a year later than it had planned last year, owing to extra time needed to complete its “safety case” testing and self-certification. “This is a multiyear journey,” says Aurora president Ossa Fisher. “A few months seemed minuscule in the grand scheme of both the opportunity that lies ahead of us and what came before.”

But barely two weeks after the announcement, the company was back to having safety operators sitting behind the wheels of the two trucks.

In a May 16 company blog post, CEO and chairman Chris Urmson said one of its truck-manufacturing partners, Paccar, had requested that change “because of certain prototype parts in their base vehicle platform.” He wrote that “after much consideration,” Aurora “respected their request and are moving the observer, who had been riding in the back of some of our trips, from the back seat to the front seat.”

The International Brotherhood of Teamsters, the union that represents drivers, would prefer to keep things that way—and has been lobbying lawmakers in such states as Texas, California, and Massachusetts to codify that in regulations. “Our position is that all trucks should have human operator requirements,” says Teamsters spokesman Matt McQuaid.

A long road ahead

Despite the upshift-downshift progress, however, Aurora is still farther down the road than other companies in this space.

Gartner analyst Jonathan Davenport rates the company as “significantly ahead” of such competitors as Plus AI, which plans to inaugurate commercial service in 2027 and in early June announced plans for an initial public offering (its second attempt to do so).

Aurora staged its IPO in 2021, which has allowed a much clearer view of its financials than what’s available from the likes of another company to make self-driving vehicles a commercial reality: Waymo. And those numbers show that running an autonomous-trucking company isn’t cheap: In the first quarter of 2025, Aurora reported a net loss of $208 million. On its Q1 earnings call in May, company executives predicted $175 million to $185 million in quarterly expenses and revenue in “the mid-single digits” over the rest of 2025.

“There’s a big difference between the operating cost today and the operating cost at scale,” Fisher tells Fast Company. “We are not making money on a per load basis today, and that’s public information.”

Aurora’s plans include not just scaling up its fleet but also upgrading its hardware—for instance, deploying a more compact version of its FirstLight Lidar sensor. Shrinking the sensing equipment could also help Aurora move closer to its goal of bringing its self-driving technology to passenger cars.

“We’ll have a next-generation of trucks in a year,” she says. “We’ll go to tens of trucks and hundreds of trucks and thousands of trucks. And as we reach scale, that’s when you get the performance metrics to be highly profitable.”

Davenport says the plan is indeed feasible, but has some doubts about the timeline. “We’re still going to be two or three years, probably,” he says. “I would still classify it as probably in the development stage of R&D.”

Aurora and other firms in the sector benefit from a market problem that needs solving: Traditional trucking companies can’t hire enough drivers to meet demand. But even then, Gartner forecasts that autonomous trucks will make up under 5% of truck fleets worldwide by 2029.

Either snow or rain or gloom of night

In the nearer term, Aurora aims to expand its “operating design domain”—the conditions under which its trucks can roll—beyond the current requirement of clear daylight. “If there’s rain in the forecast, some days we don’t launch,” Fisher says. “We’re working very rapidly to resolve any and all weather issues and see that happening later this year.”

Here, Aurora is following a common route for autonomous-vehicle projects: Start operations in ideal weather, then drive in increasingly less pleasant conditions. Waymo, for example, inaugurated service in sunny Phoenix, but when it opens for business in Washington sometime in 2026 its robotaxis will have to deal with a full spectrum of seasonal weather that, in the case of the occasional blizzard, should keep human drivers off the roads.

Unlocking commercial nighttime operation—when a driverless truck would theoretically see its greatest advantage, by virtue of not needing to sleep—is also on the to-do list for “later this summer,” Fisher says.

“We’ve been driving in night for the last three years,” she says of the firm’s testing. “It is all about securing the evidence to close the safety case.”

Aurora’s system already handles limited driving on surface streets to connect highways with the company’s terminals. “There’s a few things like turning tight corners as an 18-wheeler. That’s harder to do than exiting a highway off-ramp,” says Fisher. “But it’s a very solvable problem.”

Other autonomous-trucking firms have opted to simplify their own operating design domain by staying off public roads. Kodiak Robotics, for example, launched self-driving commercial deliveries on private land in the oil-rich Permian Basin of Texas. Gartner’s Davenport also points to such closed environments as mines and ports as easier use cases for self-driving trucks. “Autonomous haulage trucks in mines, for example, they’re already commonplace,” he says.

Aurora, however, is not just committed to operating on public roads but planning to expand its operations outside of Texas. “We’ll be opening up to Phoenix later this year and then, from there, expanding across the south of the United States,” Fisher says.

But after 22 or so hours, a truck will have to refuel, which in the case of a truck with no driver means not any old truck stop will do. Aurora plans to build its own in Phoenix to start, after which the company plans to work with unspecified third parties on building facilities to refuel and inspect Aurora’s vehicles.

Rules of the roads

Starting operations only in Texas has simplified Aurora’s regulatory operating domain, but Fisher professes confidence in Aurora’s ability to secure more green lights from other states, starting with New Mexico and Arizona and even California, which in April released proposed rules for heavy-duty autonomous trucks.

“The more and more conversations we have, and honestly, the more miles we put on the driverless truck, the more welcoming folks are,” she says. “And so it looks like the tide may be changing even in California.”

Fisher’s case for Aurora’s safety on the roads evokes that of Waymo. Like that Alphabet subsidiary, Aurora’s vehicles fuse inputs from an array of lidar, radar, and camera sensors—a distinct contrast from Tesla, which just began very limited robotaxi services in Austin relying on a no-lidar, cameras-only system.

Fisher emphasizes how each type of sensor helps provide a fuller picture: Radar excels in fog, lidar sees farther at night, cameras do better with up-close navigation. That approach to redundancy includes having “two identical brains” in the back of the cab plus a backup computer that can pull over the truck if the two primary computers fail.

Aurora and other autonomous-mobility developers may not have to worry about state regulations if a provision in the Trump-backed budget-reconciliation bill that would preempt state-level rules on AI—and therefore on self-driving vehicles—survives negotiations between the House and the Senate and the notable opposition of some Republicans.

Fisher, for her part, voices optimism about a federal framework that would allow verification of company safety cases by third-party auditors. “Before [Transportation Secretary Sean] Duffy we thought anything at the federal level might be a decade away,” she says. “We’re now more optimistic that this could be a year or two away, and we would welcome that.”

In any regulatory regime, Gartner’s Davenport emphasizes that companies have to take safety even more seriously with freight trucks—stopping distances for one are 65% longer than for a passenger car. “The risk associated with operating an autonomous truck is so much greater,” he says. But, the analyst adds, the need for automation is also much greater than in taxis: “It’s the use case that actually makes the most economic sense.”

![What Is a Markup Language? [+ 7 Examples]](https://static.semrush.com/blog/uploads/media/82/c8/82c85ebca40c95d539cf4b766c9b98f8/markup-language-sm.png)

![[Weekly funding roundup June 21-27] A sharp rise in VC inflow](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/2/220356402d6d11e9aa979329348d4c3e/Weekly-funding-1741961216560.jpg)