Bumble is stumbling. Tinder is flagging. But this go-to gay dating app is thriving

Dating app Bumble continues to lose its footing. After subpar earnings, sluggish user growth, and internal stagnation, the company has laid off 30% of its staff. Meanwhile, its dating app competitor Grindr is soaring. Among dating apps, Match Group’s properties—mostly Hinge, sometimes Tinder—lead the market. The duo’s ubiquity frame apps like Bumble and Grindr as boutique alternatives, designed for their innovative features or specialty user bases. That’s a difficult market to occupy, especially as dating app fatigue sets in and Gen Z seems to push for more in-person (and sexless) encounters. Those factors are just part of the reason why Bumble and its competitors are falling behind. But LGBTQ+ hookup app Grindr is flourishing—posting solid growth in both user acquisition and revenue. In May, Grindr CEO George Arison spoke with Fast Company about his efforts to build a broader offering on the foundation of its core location-based grid of users—including some popular new features and a foray into telemedicine. He isn’t convinced that generational patterns entirely explain the struggles of dating apps. “This whole ‘Gen Z-avoiding-apps’ thing makes no logical sense. Gen Z loves TikTok and loves Reels and thinks you can read something online and you’re an expert in it, but they’re not gonna do dating online?,” he says. “What I do think and what makes logical sense, is that if you don’t build a product that Gen Zers want, they’re not going to use it. That’s where I think some of our peers have fallen flat.” His vision is still in progress, but here’s how the company’s constant efforts to test and scale new ideas could serve as a guide to its competitors. Comparing Bumble and Grindr Bumble and Grindr both went public in the early 2020s, when the dating app market was still hot thanks to the pandemic’s digital boom. Since their IPOs, both Bumble and Grindr have hit rough waters—though Grindr managed to right itself while Bumble continues to, well, bumble. Bumble’s stock opened at $43 per share—a height it hasn’t reached since late 2021. In 2025, Bumble’s share price was hovering around $5 in early June, jumping above $6 only at the news of layoffs earlier this week. Meanwhile, Grindr—which debuted at $16.90 in 2022, initially dropped to $5, but has been above $15 since November 2024 and exceeded $20 per share since mid-April. Revenue figures have told a similar story. Founder Whitney Wolfe Herd returned to Bumble in March on the eve of some sour news: Bumble’s Q1 earnings showed an 8% decrease in revenue year-over-year. For the same quarter, Grindr’s revenue grew 25% over the prior year. Arison told Fast Company he sees the company’s performance as a reflection of the contributions that the LGBTQ+ community—he is gay himself—can make to the business world. “Part of our mission has to be we do super well as a business and we force everybody to change,” he says. Neither app releases consistent and specific user counts. Grindr appears to be growing its user base as Bumble’s gains are slow. In its Q1 earnings, Grindr reported “more than 14.5 million” monthly active users, up from “more than 13.5 million” the year prior. Bumble’s earnings are split by paying users, a focus for former CEO Lidiane Jones. While the company grew its paying app users by 11% in 2024, it has since shed 100,000 of those subscribers in 2025. What should a dating app look like? Under Arison’s leadership, Grindr has turned into an innovation powerhouse. In his May interview, Arison emphasized the creation of Albums—bundles of photos sent via chats and not directly displayed on a profile—which debuted in 2022. In 2024, Grindr users sent over two billion albums. He also pointed toward the app’s new Right Now feature, which lets users search specifically for more immediate action. In D.C. and Sydney, two of the feature’s trial markets, Arison said that “25 to 35% of our weekly active users were regularly going into the Right Now experience at least once a week.” Grindr’s new features are available for all users, though paid subscribes receive additional uses. For example, free Grindr users get to post to the Right Now feed three times a week. Down the line, the company plans to make sessions available for purchase. That’s part of Arison’s strategy: Opening new features with limitations as a bridge to paid customer conversion. “I don’t want Grindr to end up like some of our competitors, who hollowed out their products focusing only on monetization and building nothing,” Arison told Fast Company. “We are doing product-led processes—it’s not just monetize, monetize, monetize. We’re saying: Build new things, and those things will lead to revenue.” In contrast, Bumble has moved slowly with their feature rollouts. The “Opening Moves” feature debuted in 2024, allowing users to list prompts for new matches to respond to. The feature undercut Bumble’s initial mission that women should message first. Since the

Dating app Bumble continues to lose its footing. After subpar earnings, sluggish user growth, and internal stagnation, the company has laid off 30% of its staff. Meanwhile, its dating app competitor Grindr is soaring.

Among dating apps, Match Group’s properties—mostly Hinge, sometimes Tinder—lead the market. The duo’s ubiquity frame apps like Bumble and Grindr as boutique alternatives, designed for their innovative features or specialty user bases. That’s a difficult market to occupy, especially as dating app fatigue sets in and Gen Z seems to push for more in-person (and sexless) encounters. Those factors are just part of the reason why Bumble and its competitors are falling behind.

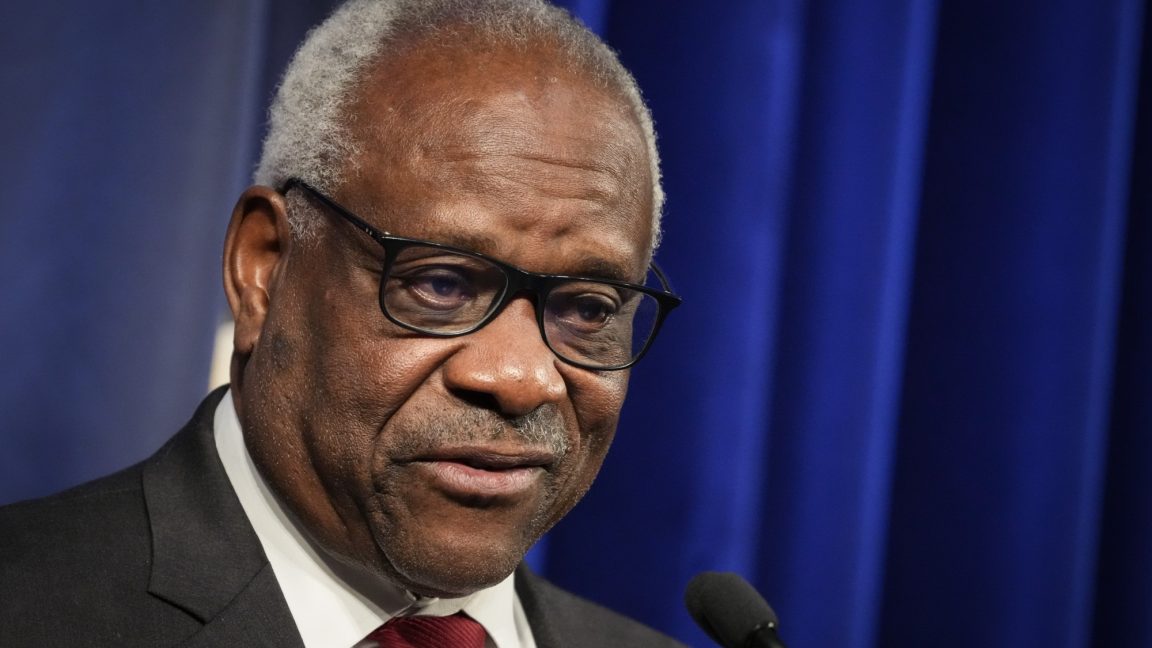

But LGBTQ+ hookup app Grindr is flourishing—posting solid growth in both user acquisition and revenue. In May, Grindr CEO George Arison spoke with Fast Company about his efforts to build a broader offering on the foundation of its core location-based grid of users—including some popular new features and a foray into telemedicine. He isn’t convinced that generational patterns entirely explain the struggles of dating apps.

“This whole ‘Gen Z-avoiding-apps’ thing makes no logical sense. Gen Z loves TikTok and loves Reels and thinks you can read something online and you’re an expert in it, but they’re not gonna do dating online?,” he says. “What I do think and what makes logical sense, is that if you don’t build a product that Gen Zers want, they’re not going to use it. That’s where I think some of our peers have fallen flat.”

His vision is still in progress, but here’s how the company’s constant efforts to test and scale new ideas could serve as a guide to its competitors.

Comparing Bumble and Grindr

Bumble and Grindr both went public in the early 2020s, when the dating app market was still hot thanks to the pandemic’s digital boom. Since their IPOs, both Bumble and Grindr have hit rough waters—though Grindr managed to right itself while Bumble continues to, well, bumble.

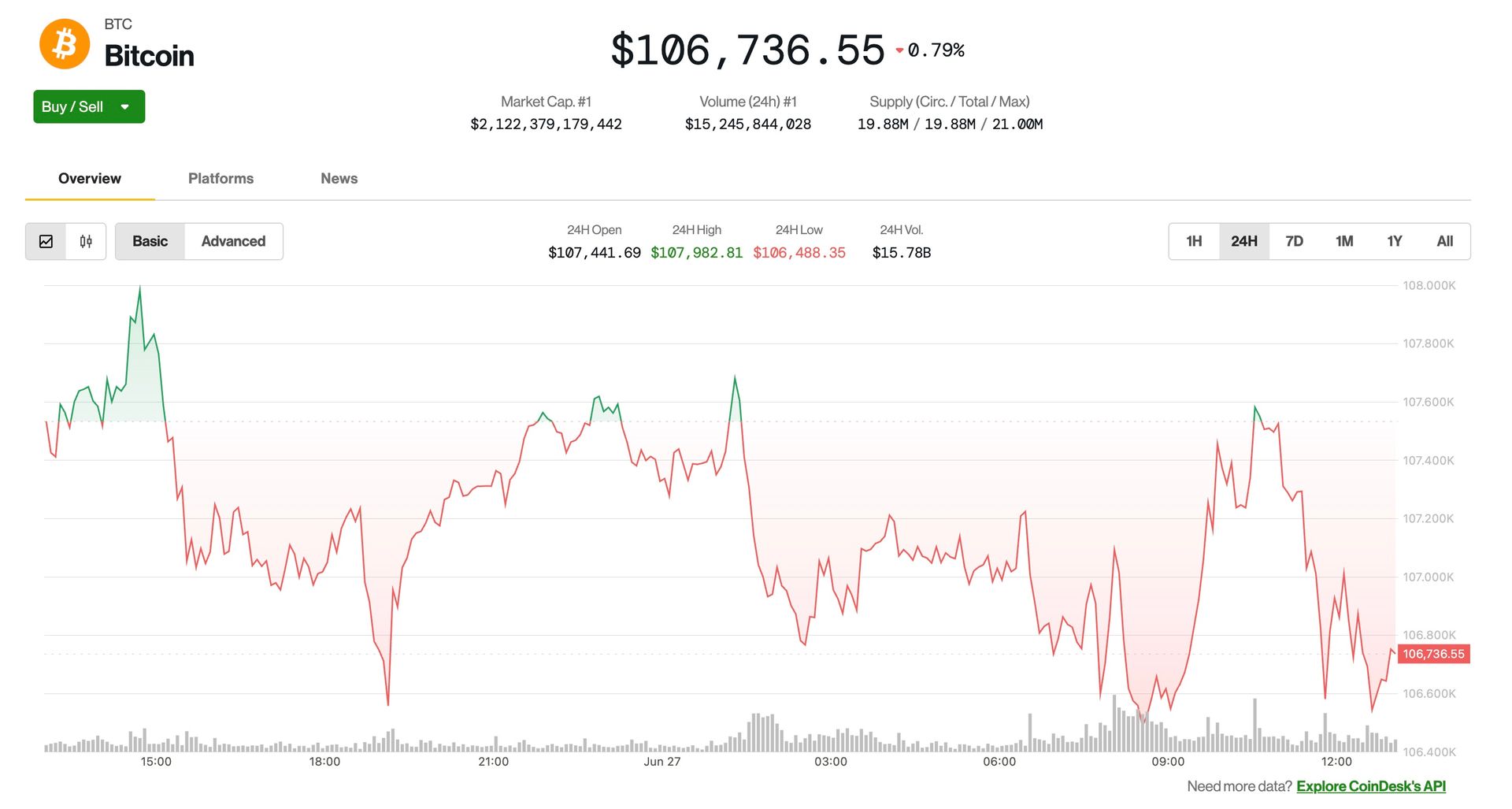

Bumble’s stock opened at $43 per share—a height it hasn’t reached since late 2021. In 2025, Bumble’s share price was hovering around $5 in early June, jumping above $6 only at the news of layoffs earlier this week. Meanwhile, Grindr—which debuted at $16.90 in 2022, initially dropped to $5, but has been above $15 since November 2024 and exceeded $20 per share since mid-April.

Revenue figures have told a similar story. Founder Whitney Wolfe Herd returned to Bumble in March on the eve of some sour news: Bumble’s Q1 earnings showed an 8% decrease in revenue year-over-year. For the same quarter, Grindr’s revenue grew 25% over the prior year.

Arison told Fast Company he sees the company’s performance as a reflection of the contributions that the LGBTQ+ community—he is gay himself—can make to the business world. “Part of our mission has to be we do super well as a business and we force everybody to change,” he says.

Neither app releases consistent and specific user counts. Grindr appears to be growing its user base as Bumble’s gains are slow. In its Q1 earnings, Grindr reported “more than 14.5 million” monthly active users, up from “more than 13.5 million” the year prior. Bumble’s earnings are split by paying users, a focus for former CEO Lidiane Jones. While the company grew its paying app users by 11% in 2024, it has since shed 100,000 of those subscribers in 2025.

What should a dating app look like?

Under Arison’s leadership, Grindr has turned into an innovation powerhouse. In his May interview, Arison emphasized the creation of Albums—bundles of photos sent via chats and not directly displayed on a profile—which debuted in 2022. In 2024, Grindr users sent over two billion albums. He also pointed toward the app’s new Right Now feature, which lets users search specifically for more immediate action. In D.C. and Sydney, two of the feature’s trial markets, Arison said that “25 to 35% of our weekly active users were regularly going into the Right Now experience at least once a week.”

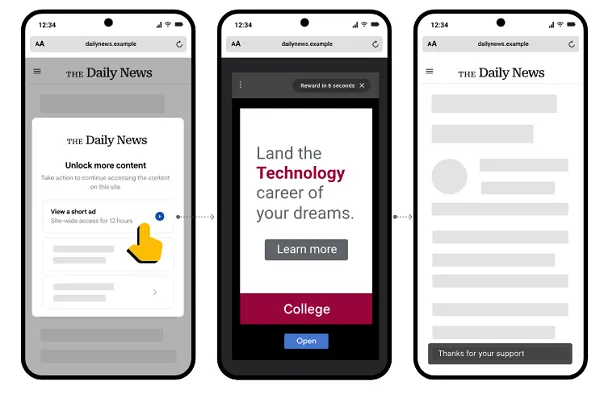

Grindr’s new features are available for all users, though paid subscribes receive additional uses. For example, free Grindr users get to post to the Right Now feed three times a week. Down the line, the company plans to make sessions available for purchase. That’s part of Arison’s strategy: Opening new features with limitations as a bridge to paid customer conversion.

“I don’t want Grindr to end up like some of our competitors, who hollowed out their products focusing only on monetization and building nothing,” Arison told Fast Company. “We are doing product-led processes—it’s not just monetize, monetize, monetize. We’re saying: Build new things, and those things will lead to revenue.”

In contrast, Bumble has moved slowly with their feature rollouts. The “Opening Moves” feature debuted in 2024, allowing users to list prompts for new matches to respond to. The feature undercut Bumble’s initial mission that women should message first. Since then, they’ve also instituted ID verification and date-sharing safety features. Many of the app’s most compelling features—like backtracking left swipes, Travel Mode, and Incognito Mode—are only available to paid users.

With dating app fatigue on the rise, both Bumble and Grindr have also expanded into alternate markets. Both have emphasized the role of friendship and platonic encounters on their apps, with Arison promoting Grindr’s ongoing effort to become the “global gayborhood in your pocket,” noting “Our younger, 18-plus cohort wants to be in an environment where there are older people as well. Friendships between younger and older people are much more common in our community.”

Bumble launched its friend-focused Bumble B.F.F. in 2016, and broke it out into a stand-alone app, Bumble for Friends, in 2023. While Bumble for Friends doesn’t release stand-alone user numbers, its million-plus Google Play downloads is dwarfed by Bumble’s more than 50 million downloads. Grindr’s “gayborhood” model also flows easily with the original app; users have been employing Grindr for non-dating activities since its advent. By spinning their Friends function out into a separate app, Bumble must seek out an entirely separate user base.

In this area, Grindr is making a similarly big bet on how it can show up in different ways for its users. The company recently launched Woodwork, a telemedicine company selling erectile dysfunction pills, in Illinois and Pennsylvania. Arison also predicted that Grindr would expand into “haircare, skincare, and other things of that nature.”

“When I started talking to shareholders, part of the conversation was: What do we want Grindr to be? Just a dating app or something more?” Arison told Fast Company. “Their view was very strong: We want to be a lot more.”

![What Is a Markup Language? [+ 7 Examples]](https://static.semrush.com/blog/uploads/media/82/c8/82c85ebca40c95d539cf4b766c9b98f8/markup-language-sm.png)

![[Weekly funding roundup June 21-27] A sharp rise in VC inflow](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/2/220356402d6d11e9aa979329348d4c3e/Weekly-funding-1741961216560.jpg)