Trump wants to kill EVs—but he’s just giving BYD an advantage over Detroit

The fastest-growing car brand in the U.K. is BYD, the Chinese automaker behind electric cars like the new £16,000 ($21,600) Surf. Last month, the brand outsold Tesla in Europe for the first time. BYD is also the fastest-growing car brand in Brazil, where EV sales jumped up 85% last year. In the capital city of Brasilia, BYD now outsells all other cars, whether they’re gas or electric. In Nepal, where seven out of every 10 cars imported last year was an EV, BYD’s electric models vie with those from Tata, an Indian brand. In Thailand, another Chinese company called Changan is quickly gaining market share with its electric cars. The world is going electric: The International Energy Agency recently projected that one in four cars sold this year will be an EV. But the U.S. is lagging behind, and the Trump administration’s assault on EVs will slow down the industry more. That doesn’t bode well for the future of American automakers. “Probably the most dire scenario is that the U.S. becomes somewhat isolated in an idiosyncratic market, with lots of big pickups and SUVs that don’t sell in any other market, and that are still predominantly fossil fuel,” says John Paul MacDuffie, a management professor at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. “And we’re not exposed to competition from some of the new manufacturers or some of the new technologies—not only electric but autonomous and connected.” China already had a long head start Even before Trump—who has said that Biden’s support for EVs was a “Marxist hoax”—American car companies were behind their Chinese counterparts on the path to electrification. One factor was China’s continuous support, which started more than 15 years ago. “There were changes to the policy and subsidies, but generally it [was clear] that the government thinks this is good technology,” says Ilaria Mazzocco, deputy director at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a bipartisan think tank. “So if you’re going to buy an electric vehicle, it’s not like in two years things are going to change dramatically.” Before China started pouring billions into the sector and made EV competitiveness a national priority, BYD was already innovative and lobbying for government support. The company, which had been founded in 1995 as a battery manufacturer, was “entrepreneurial and ready to take up the challenge,” Mazzocco says. Electric cars also got early support in the U.S.—Tesla got a $465 million low-interest loan from the Department of Energy in 2009, benefitted from EV tax credits for consumers, and got a major boost from California’s zero-emission vehicle credits. But China’s support went farther and faster. Around 60% of new car models sold in China are now electric, five times more than what’s available in the U.S., according to the IEA. From the beginning, Chinese automakers were laser-focused on the cost of EVs. By 2023, around 60% of electric cars in China were cheaper than their gas equivalents without subsidies, the IEA says. In many cases, the technology is more advanced than EV tech from some Western automakers, as Chinese companies race to improve batteries and software. Chinese companies are 30% faster than legacy automakers at developing new EV models, according to one analysis. Ford CEO Jim Farley admitted last year that he’d been driving an electric car from Xiaomi—a Chinese smartphone manufacturer that started making EVs—and said he “doesn’t want to give it up.” “There’s no doubt” the future is electric Still, American automakers know that their future is electric. “There’s no doubt about it,” says Ellen Hughes-Cromwick, the former chief economist at Ford. Companies have already spent billions on the transition. But right now, the legacy automakers face cost challenges. Engineering new batteries and new vehicles obviously has a steep capital cost, versus the depreciated capital costs for continuing to make internal combustion engine cars. And although EV sales grew faster last year than gas car sales, they aren’t growing as quickly as automakers hoped. “I’ve done the math,” Hughes-Cromwick says. “It’s not great right now for our domestic manufacturers, because they’ve got low volume but high fixed costs on the new technology, and low capital costs and high volume on the old tech.” As more EVs sell, companies can get to cost and pricing parity. Policies could help make the transition easier, she says, such as keeping tax credits in place for EVs. Instead, the federal government is pushing hard in the other direction. Trump froze billions in spending on EV charging infrastructure, and blocked subsidies for factories making batteries, despite the fact that those factories were creating American jobs. Congress is trying to get rid of the consumer tax credit and add a new annual fee for EV owners (though the fee is meant to replace the gas tax, the total cost would be higher than drivers with gas cars currently spend on it). C

The fastest-growing car brand in the U.K. is BYD, the Chinese automaker behind electric cars like the new £16,000 ($21,600) Surf. Last month, the brand outsold Tesla in Europe for the first time.

BYD is also the fastest-growing car brand in Brazil, where EV sales jumped up 85% last year. In the capital city of Brasilia, BYD now outsells all other cars, whether they’re gas or electric. In Nepal, where seven out of every 10 cars imported last year was an EV, BYD’s electric models vie with those from Tata, an Indian brand. In Thailand, another Chinese company called Changan is quickly gaining market share with its electric cars.

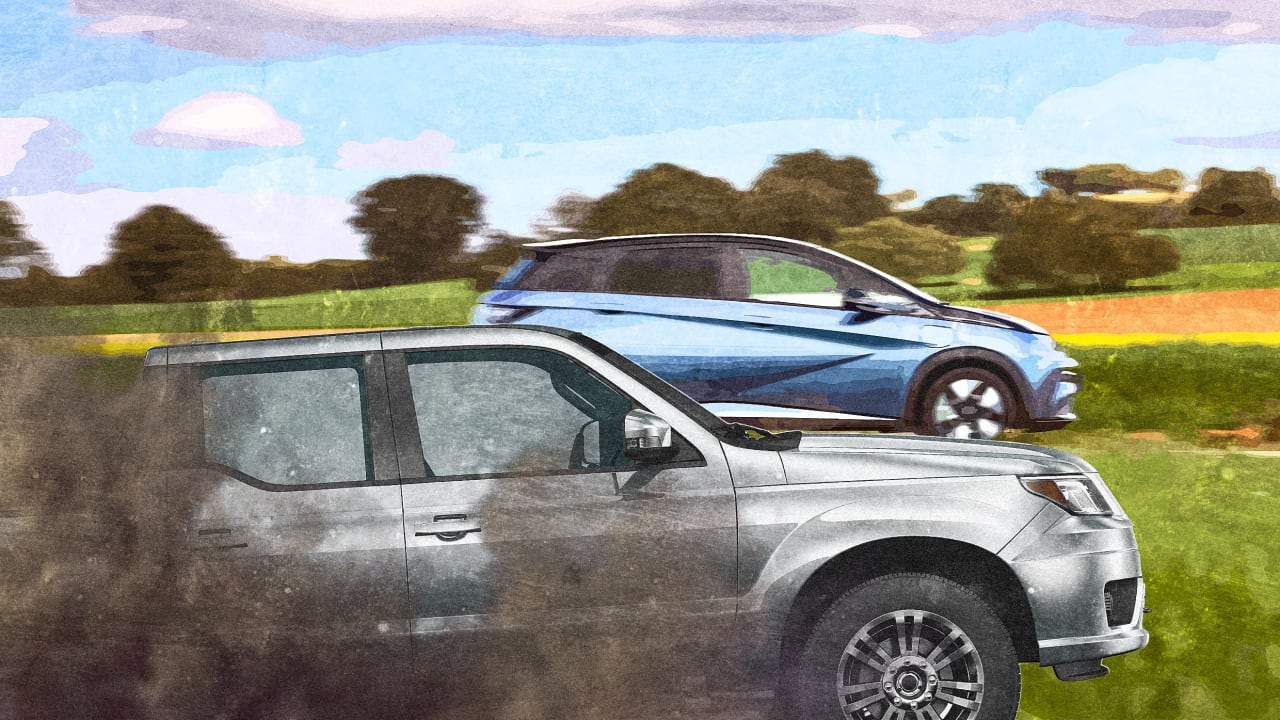

The world is going electric: The International Energy Agency recently projected that one in four cars sold this year will be an EV. But the U.S. is lagging behind, and the Trump administration’s assault on EVs will slow down the industry more. That doesn’t bode well for the future of American automakers.

“Probably the most dire scenario is that the U.S. becomes somewhat isolated in an idiosyncratic market, with lots of big pickups and SUVs that don’t sell in any other market, and that are still predominantly fossil fuel,” says John Paul MacDuffie, a management professor at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. “And we’re not exposed to competition from some of the new manufacturers or some of the new technologies—not only electric but autonomous and connected.”

China already had a long head start

Even before Trump—who has said that Biden’s support for EVs was a “Marxist hoax”—American car companies were behind their Chinese counterparts on the path to electrification. One factor was China’s continuous support, which started more than 15 years ago. “There were changes to the policy and subsidies, but generally it [was clear] that the government thinks this is good technology,” says Ilaria Mazzocco, deputy director at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a bipartisan think tank. “So if you’re going to buy an electric vehicle, it’s not like in two years things are going to change dramatically.”

Before China started pouring billions into the sector and made EV competitiveness a national priority, BYD was already innovative and lobbying for government support. The company, which had been founded in 1995 as a battery manufacturer, was “entrepreneurial and ready to take up the challenge,” Mazzocco says.

Electric cars also got early support in the U.S.—Tesla got a $465 million low-interest loan from the Department of Energy in 2009, benefitted from EV tax credits for consumers, and got a major boost from California’s zero-emission vehicle credits. But China’s support went farther and faster. Around 60% of new car models sold in China are now electric, five times more than what’s available in the U.S., according to the IEA.

From the beginning, Chinese automakers were laser-focused on the cost of EVs. By 2023, around 60% of electric cars in China were cheaper than their gas equivalents without subsidies, the IEA says. In many cases, the technology is more advanced than EV tech from some Western automakers, as Chinese companies race to improve batteries and software.

Chinese companies are 30% faster than legacy automakers at developing new EV models, according to one analysis. Ford CEO Jim Farley admitted last year that he’d been driving an electric car from Xiaomi—a Chinese smartphone manufacturer that started making EVs—and said he “doesn’t want to give it up.”

“There’s no doubt” the future is electric

Still, American automakers know that their future is electric. “There’s no doubt about it,” says Ellen Hughes-Cromwick, the former chief economist at Ford. Companies have already spent billions on the transition. But right now, the legacy automakers face cost challenges. Engineering new batteries and new vehicles obviously has a steep capital cost, versus the depreciated capital costs for continuing to make internal combustion engine cars. And although EV sales grew faster last year than gas car sales, they aren’t growing as quickly as automakers hoped.

“I’ve done the math,” Hughes-Cromwick says. “It’s not great right now for our domestic manufacturers, because they’ve got low volume but high fixed costs on the new technology, and low capital costs and high volume on the old tech.”

As more EVs sell, companies can get to cost and pricing parity. Policies could help make the transition easier, she says, such as keeping tax credits in place for EVs. Instead, the federal government is pushing hard in the other direction.

Trump froze billions in spending on EV charging infrastructure, and blocked subsidies for factories making batteries, despite the fact that those factories were creating American jobs. Congress is trying to get rid of the consumer tax credit and add a new annual fee for EV owners (though the fee is meant to replace the gas tax, the total cost would be higher than drivers with gas cars currently spend on it). Congress is also trying to block California’s plans to transition to zero-emissions vehicles. Tariffs have added to the economic pressure.

Despite all of this, the long-term strategy for U.S. automakers isn’t likely to change. “The time horizon for product cycles, facility planning, and supply chain planning is very long,” says MacDuffie. “They’re global companies, so they’re not just planning for the U.S. market. I have been predicting that U.S. companies will continues to pursue a long-term strategy which is premised on electrification hitting most markets and most products. I think it would take years of a hostile economic and policy environment for them to back away from that in a big way.”

It’s too early to count out American automakers, Hughes-Cromwick says, noting that they could pull forward on software, for example. But as Trump pushes for anti-EV policy, companies are slowing some electric investments, and are likely to keep falling behind as Chinese companies race forward. A year ago, the IEA predicted that EVs would hit 50% of car sales in the U.S. by 2030; the agency has now revised that to 20%.

With steep tariffs keeping cheap Chinese EVs out of the U.S., there’s less incentive for American automakers to innovate as quickly on electric vehicles. The current tax bill also reduces support for EV battery makers and slashes funding for research and development of new battery tech through the Department of Energy.

Meanwhile, Chinese EVs are spreading around the rest of the world. Last year, BYD surpassed Tesla in global vehicle sales. BYD’s stock price has climbed around 59% on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange since the beginning of 2025, while Tesla’s has declined around 11% on the Nasdaq, despite some recovery in recent weeks. In Brazil, BYD is now rebuilding a former Ford factory, on a street that a local politician wants to rename from Henry Ford Avenue to BYD Avenue.

“Once consumers have access to these vehicles, they’re really interested,” says Mazzocco. For a growing middle class in emerging countries, “their first car might be a Chinese electric vehicle.”