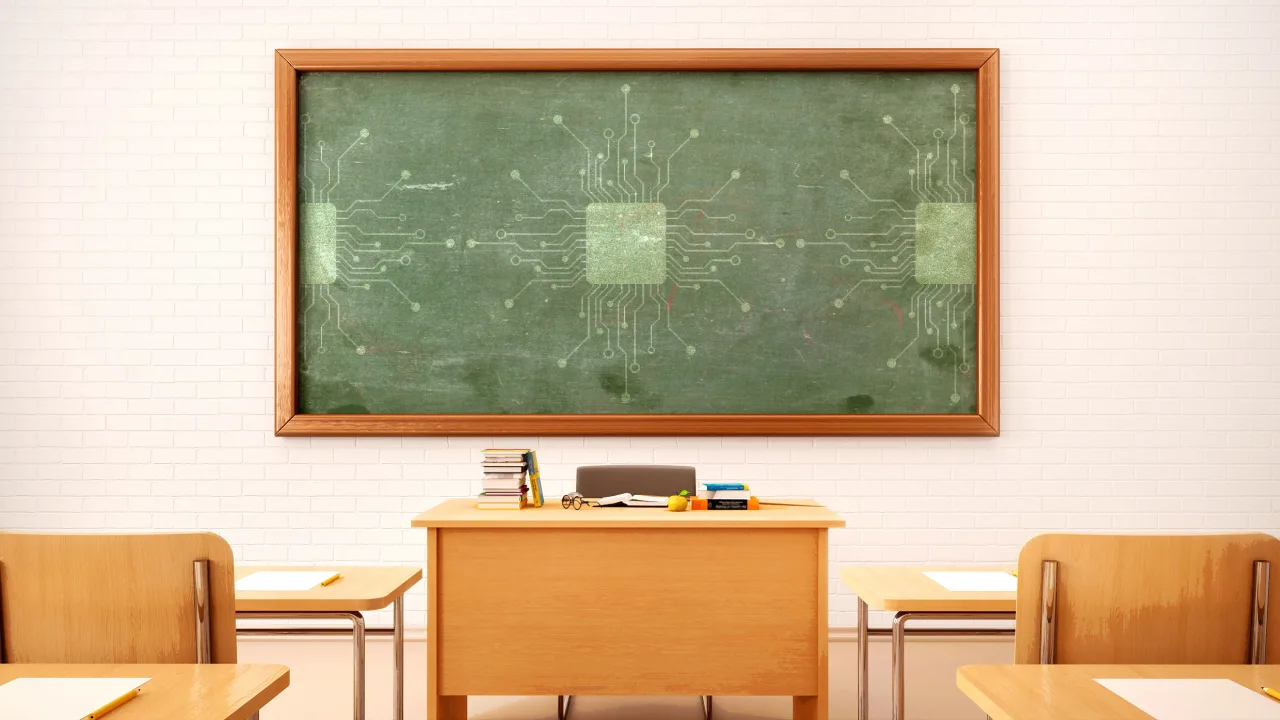

Teaching AI isn’t enough—we need to teach wisdom, too

Artificial intelligence is shaking the intellectual, emotional, and economic foundations of the world. A glance at mainstream or social media confirms that the world ahead will look nothing like the one we’re leaving behind. Technological disruption is nothing new. From bronze smelting in Benin and steel forging in Japan to Themistocles’s naval buildup in ancient Greece, history shows that transformative technologies spark societal shifts and national urgency. Today’s urgency is AI. The White House’s recent executive order (EO) on AI education echoes past anxieties—this time, about China’s rapid advancement. You may have missed this EO amid the recent flood of them. But it’s a pivotal moment. Though well-intentioned, the EO lacks the depth needed for a truly informed AI educational policy. The EO defines its mission as providing “opportunities to cultivate the skills and understanding necessary to use and create the next generation of AI technology.” It outlines three imperatives: “Expose our students to AI at an early age.” Train teachers to “effectively incorporate AI into their teaching methods.” Promote AI literacy to “develop an AI-ready workforce.” These steps are necessary. AI is a profound shift, one that exposes long-standing deficiencies in our educational system—particularly our neglect of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). Still, the EO falls short in three key areas. Speaking as president and CEO of the Center of Science and Industry, a board member of the National Academies, and a lifelong STEM advocate, I say this: You cannot teach AI without also teaching critical thinking, ethics, and wisdom. Our national conversation must expand beyond technical training. As AI (and eventually artificial general intelligence) integrates into every part of life, we face a stark choice: Do we become passive consumers of knowledge, or do we intentionally cultivate wisdom? Technical proficiency alone turns us into carbon versions of AI. Instead, we need a cultural shift—one that champions critical thinking, ethical reasoning, and curiosity in classrooms, workplaces, and homes. The goal isn’t just to understand AI, but to navigate the world it creates. Techno-optimism must be balanced with rigorous intellectual and moral interrogation—or the “doomers” may be right. Though the EO doesn’t address the human-AI relationship, I’ll give it the benefit of the doubt—it’s not a full policy, but a starting point. I hope future policy goes further, confronting AI’s risks and outlining how education and society should respond—both philosophically and practically. For what it’s worth, my ideal AI curriculum would include more than practical skills. It would explore: Martin Heidegger’s insights on how technology shapes experience Nick Bostrom’s “paper clip” thought experiment Shoshana Zuboff’s critique of surveillance capitalism Soon, AI won’t need to be taught—it will be omnipresent. In the 1990s, we trained students to use a mouse and browse the web. But intuitive design soon made that obsolete. The same is happening with AI—only faster. Rather than focus on today’s tools, AI education should teach how to understand technology’s evolution. Computer scientist Alan Kay once said, “Technology is anything that was invented after you were born.” Maintaining global leadership requires more than technical prowess—it demands cultural vision. After Sputnik, America feared falling behind in the space race. In the 1990s, it was Japan. Now, it’s China. But the true question is: Which nation will use AI to become the better society? French philosopher and diplomat Alexis de Tocqueville once said, “America is great because it is good. If America ceases to be good, America will cease to be great.” That quote echoes as I reflect on the EO and our future. To lead in AI, we must prioritize wisdom over raw intelligence. That greatness won’t come from executive orders—but from the strength of our social order.

Artificial intelligence is shaking the intellectual, emotional, and economic foundations of the world. A glance at mainstream or social media confirms that the world ahead will look nothing like the one we’re leaving behind.

Technological disruption is nothing new. From bronze smelting in Benin and steel forging in Japan to Themistocles’s naval buildup in ancient Greece, history shows that transformative technologies spark societal shifts and national urgency.

Today’s urgency is AI. The White House’s recent executive order (EO) on AI education echoes past anxieties—this time, about China’s rapid advancement.

You may have missed this EO amid the recent flood of them. But it’s a pivotal moment. Though well-intentioned, the EO lacks the depth needed for a truly informed AI educational policy.

The EO defines its mission as providing “opportunities to cultivate the skills and understanding necessary to use and create the next generation of AI technology.” It outlines three imperatives:

- “Expose our students to AI at an early age.”

- Train teachers to “effectively incorporate AI into their teaching methods.”

- Promote AI literacy to “develop an AI-ready workforce.”

These steps are necessary. AI is a profound shift, one that exposes long-standing deficiencies in our educational system—particularly our neglect of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM).

Still, the EO falls short in three key areas. Speaking as president and CEO of the Center of Science and Industry, a board member of the National Academies, and a lifelong STEM advocate, I say this: You cannot teach AI without also teaching critical thinking, ethics, and wisdom.

Our national conversation must expand beyond technical training. As AI (and eventually artificial general intelligence) integrates into every part of life, we face a stark choice: Do we become passive consumers of knowledge, or do we intentionally cultivate wisdom?

Technical proficiency alone turns us into carbon versions of AI. Instead, we need a cultural shift—one that champions critical thinking, ethical reasoning, and curiosity in classrooms, workplaces, and homes.

The goal isn’t just to understand AI, but to navigate the world it creates. Techno-optimism must be balanced with rigorous intellectual and moral interrogation—or the “doomers” may be right.

Though the EO doesn’t address the human-AI relationship, I’ll give it the benefit of the doubt—it’s not a full policy, but a starting point. I hope future policy goes further, confronting AI’s risks and outlining how education and society should respond—both philosophically and practically.

For what it’s worth, my ideal AI curriculum would include more than practical skills. It would explore:

- Martin Heidegger’s insights on how technology shapes experience

- Nick Bostrom’s “paper clip” thought experiment

- Shoshana Zuboff’s critique of surveillance capitalism

Soon, AI won’t need to be taught—it will be omnipresent. In the 1990s, we trained students to use a mouse and browse the web. But intuitive design soon made that obsolete. The same is happening with AI—only faster.

Rather than focus on today’s tools, AI education should teach how to understand technology’s evolution.

Computer scientist Alan Kay once said, “Technology is anything that was invented after you were born.” Maintaining global leadership requires more than technical prowess—it demands cultural vision.

After Sputnik, America feared falling behind in the space race. In the 1990s, it was Japan. Now, it’s China. But the true question is: Which nation will use AI to become the better society?

French philosopher and diplomat Alexis de Tocqueville once said, “America is great because it is good. If America ceases to be good, America will cease to be great.” That quote echoes as I reflect on the EO and our future.

To lead in AI, we must prioritize wisdom over raw intelligence. That greatness won’t come from executive orders—but from the strength of our social order.