How these hot pink chairs became a symbol of the L.A. protests

Since Friday, protests over immigration raids have erupted across Los Angeles. The demonstrations escalated after President Trump deployed the National Guard into the city on Saturday. Troops used aggressive tactics to disperse the rallies, including firing rubber bullets, using flash-bang stun grenades, and spraying tear gas into the crowds. The photographs emerging from the weekend are unsettling. An unlikely symbol of what’s happening in the city has emerged in images of protesters near Gloria Molina Grand Park taking cover behind hot pink benches, chairs, and tables. Demonstrators frequently use what’s available around them as barricades, and often that’s street furniture: trash cans, benches, construction signs—anything that can be picked up and moved. But those hot pink seats tell an L.A.–specific story of the conflict at hand. [Photo: Apu Gomes/Getty Images] Designed by the architecture firm Rios, Grand Park has been at the center of the pro-immigrant demonstrations. It is adjacent to Los Angeles’s City Hall and just a few blocks away from the Metropolitan Detention Center, a site where protesters gathered and where ICE is holding its detainees. The park itself was designed to represent Los Angeles’s multicultural population and to be “a park for everyone.” Rios was adamant that the public space feature movable seating—like in New York’s Bryant Park and Paris’s Luxembourg Gardens—so that visitors had flexibility in how they used it (aside from sleeping on them), so they designed a custom collection to meet those needs. The furniture is made from powder-coated aluminum, and the hot pink color nods to the hue of the flowers that grow in equatorial countries, where many of the city’s residents have roots, and to the bougainvillea vines found throughout the city. When the park opened 11 years ago, it was furnished with hundreds of these pieces, more specifically 26 freestanding benches, 41 wall-mounted benches, 120 cafe tables, and 240 cafe chairs, all made by the Southern California manufacturer Janus et Cie. Grand Molina Park, ca. 2012. [Photo: Channone Arif/Flickr] “The park is a place for people to come together and find community,” says Andy Lantz, the co-CEO and creative director of Rios. “This idea of being able to reconfigure the use of the space with movable furniture was fundamental to making it a park for all.” In the years since it opened, the park has become the gathering place Rios intended, hosting weekend dance parties, morning yoga classes, food trucks, and political rallies. The community-focused nature of the space represents what’s at risk because of the raids. Angelenos are worried about their friends and neighbors and are doing what they can to protect their communities and civic values. Amid this context, the furniture found a new use to provide security and protection. While “endless configurations” was part of the furniture design brief, Lantz never imagined what that might mean in the context of a demonstration. He experienced a flood of emotion when he first saw photographs of protesters using the powder-coated aluminum furniture as a shield. The benches, which are about six feet long and weigh 70 pounds, have just the right dimensions to cover a human body when propped on its side; a chair, which weighs about 25 pounds, can be held up by its wire frame and crouched behind. “I’ve looked at [the photos] multiple times today—I’ve been proud, I’ve been upset, I’ve been startled,” he says. “Seeing our work repurposed in a moment of collective action was humbling and powerful.” Since Grand Park opened, Rios has used the Civic collection of street furniture in parks it designed in Palm Springs and Houston, among other cities. Bright blue editions are also present in New York’s Brooklyn Bridge Park. Lantz wonders if the events that happened over the last few days in L.A. will inspire designers to think about the parks they make in new ways. “As designers, do you need to start thinking of public space as defensible for these types of actions?” he says. It seems that the design brief for street furniture just got a lot more complicated.

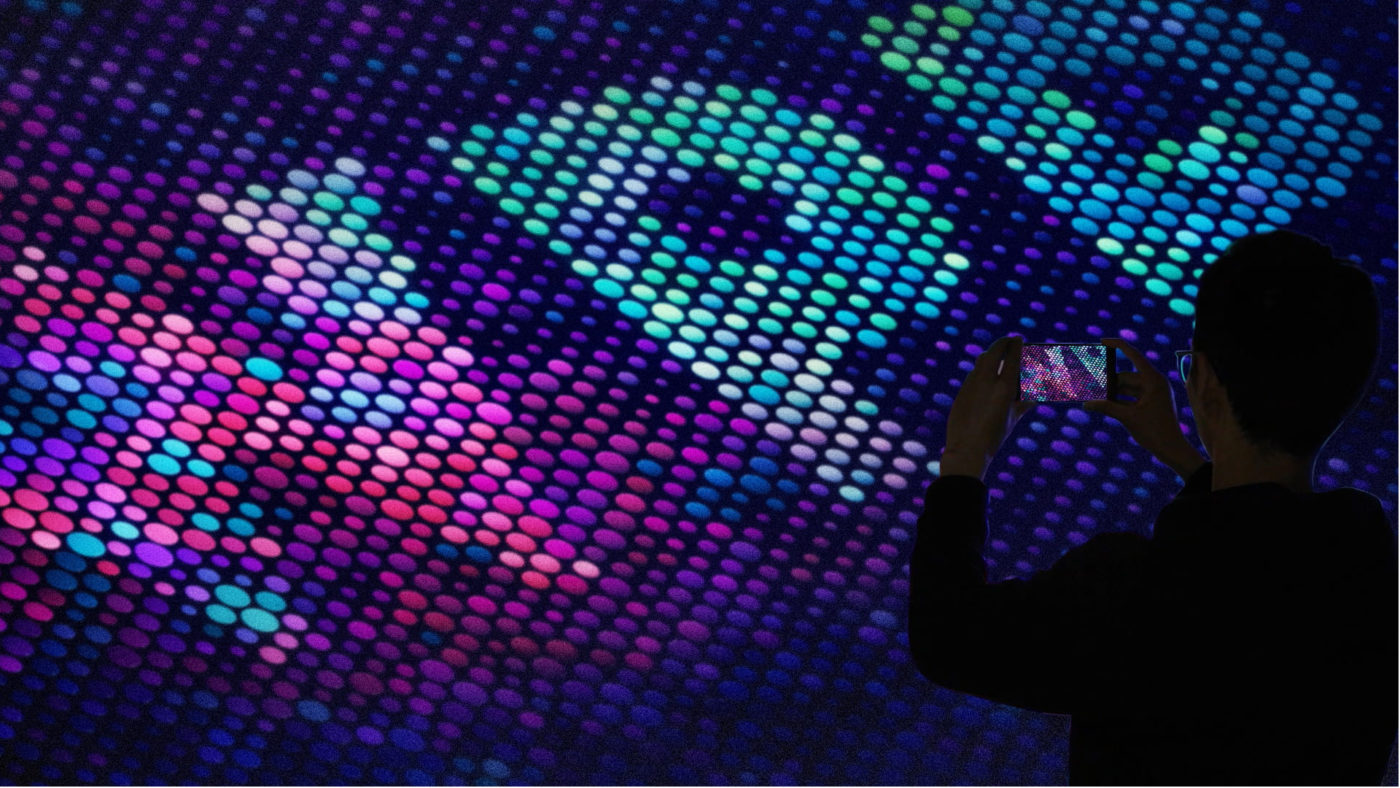

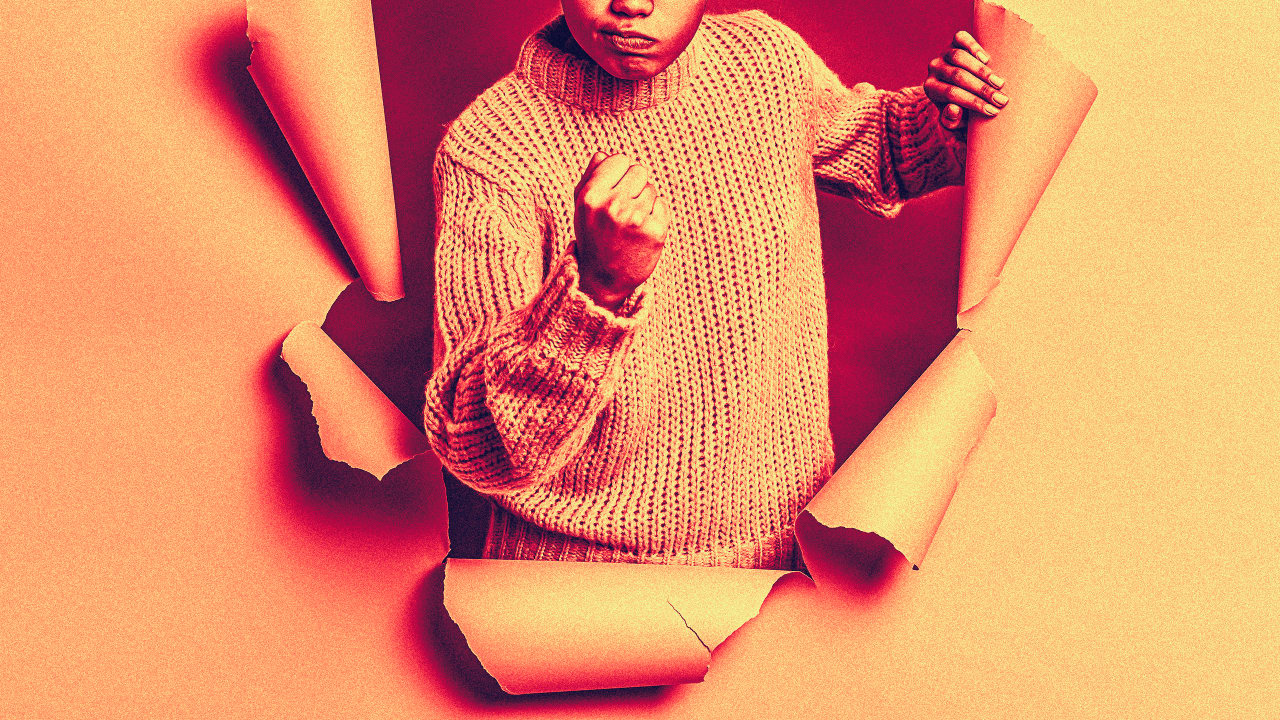

Since Friday, protests over immigration raids have erupted across Los Angeles. The demonstrations escalated after President Trump deployed the National Guard into the city on Saturday. Troops used aggressive tactics to disperse the rallies, including firing rubber bullets, using flash-bang stun grenades, and spraying tear gas into the crowds. The photographs emerging from the weekend are unsettling.

An unlikely symbol of what’s happening in the city has emerged in images of protesters near Gloria Molina Grand Park taking cover behind hot pink benches, chairs, and tables. Demonstrators frequently use what’s available around them as barricades, and often that’s street furniture: trash cans, benches, construction signs—anything that can be picked up and moved. But those hot pink seats tell an L.A.–specific story of the conflict at hand.

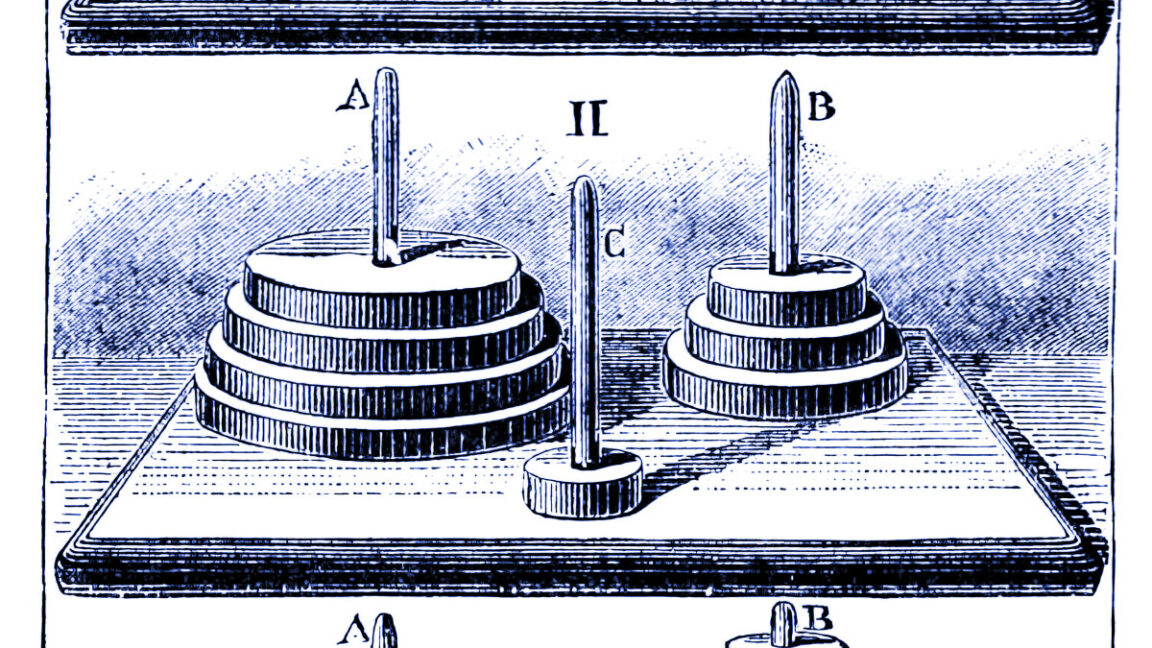

Designed by the architecture firm Rios, Grand Park has been at the center of the pro-immigrant demonstrations. It is adjacent to Los Angeles’s City Hall and just a few blocks away from the Metropolitan Detention Center, a site where protesters gathered and where ICE is holding its detainees. The park itself was designed to represent Los Angeles’s multicultural population and to be “a park for everyone.”

Rios was adamant that the public space feature movable seating—like in New York’s Bryant Park and Paris’s Luxembourg Gardens—so that visitors had flexibility in how they used it (aside from sleeping on them), so they designed a custom collection to meet those needs.

The furniture is made from powder-coated aluminum, and the hot pink color nods to the hue of the flowers that grow in equatorial countries, where many of the city’s residents have roots, and to the bougainvillea vines found throughout the city. When the park opened 11 years ago, it was furnished with hundreds of these pieces, more specifically 26 freestanding benches, 41 wall-mounted benches, 120 cafe tables, and 240 cafe chairs, all made by the Southern California manufacturer Janus et Cie.

“The park is a place for people to come together and find community,” says Andy Lantz, the co-CEO and creative director of Rios. “This idea of being able to reconfigure the use of the space with movable furniture was fundamental to making it a park for all.”

In the years since it opened, the park has become the gathering place Rios intended, hosting weekend dance parties, morning yoga classes, food trucks, and political rallies. The community-focused nature of the space represents what’s at risk because of the raids. Angelenos are worried about their friends and neighbors and are doing what they can to protect their communities and civic values. Amid this context, the furniture found a new use to provide security and protection.

While “endless configurations” was part of the furniture design brief, Lantz never imagined what that might mean in the context of a demonstration. He experienced a flood of emotion when he first saw photographs of protesters using the powder-coated aluminum furniture as a shield. The benches, which are about six feet long and weigh 70 pounds, have just the right dimensions to cover a human body when propped on its side; a chair, which weighs about 25 pounds, can be held up by its wire frame and crouched behind. “I’ve looked at [the photos] multiple times today—I’ve been proud, I’ve been upset, I’ve been startled,” he says. “Seeing our work repurposed in a moment of collective action was humbling and powerful.”

Since Grand Park opened, Rios has used the Civic collection of street furniture in parks it designed in Palm Springs and Houston, among other cities. Bright blue editions are also present in New York’s Brooklyn Bridge Park.

Lantz wonders if the events that happened over the last few days in L.A. will inspire designers to think about the parks they make in new ways. “As designers, do you need to start thinking of public space as defensible for these types of actions?” he says. It seems that the design brief for street furniture just got a lot more complicated.