Has AI already rotted my brain?

Five years ago, I bought an e-bike. At the time, the motor-equipped two-wheelers were burdened with an iffy reputation. Was it way easier to get up a hill on one than on a bike without a battery? Absolutely. Did that mean people who rode them were lazy or even cheaters? Some cycling enthusiasts thought so. But what if the boost provided by your e-bike motivated you to make longer trips and more of them—all powered, in part, by your own pedaling? Having logged almost 10,000 miles on my Gazelle, I’m certain it’s been a guilt-free boon to my well-being. Data backs me up. I thought about that recently while reading about a new study conducted at MIT’s Media Lab. Researchers divided subjects ages 18 to 39 into three groups and had them write essays on topics drawn from the SAT questions answered by college applicants, such as “Do works of art have the power to change people’s lives?” One group relied entirely on unassisted brainpower to complete the essay. A second group could use a search engine. And the third could call on ChatGPT. The study subjects wore EEG helmets that captured their brain activity as they worked. After analyzing that data, the researchers concluded that access to ChatGPT didn’t just make composing an essay easier. It made it too easy, in ways that might negatively impact people’s long-term ability to think for themselves. In some cases, the ChatGPT users merely cut and pasted text the chatbot had generated; not surprisingly, they exhibited little sense of ownership over the finished product compared to those who didn’t have a computerized ghost on tap. “Due to the instant availability of the response to almost any question, LLMs can possibly make a learning process feel effortless, and prevent users from attempting any independent problem solving,” the researchers wrote in their report. “By simplifying the process of obtaining answers, LLMs could decrease student motivation to perform independent research and generate solutions. Lack of mental stimulation could lead to a decrease in cognitive development and negatively impact memory.” The study reached those sobering conclusions in the context of young people growing up in an era of bountiful access to AI. But the alarms it set off also left me worried about the technology’s impact on my own brain. I have long considered AI an e-bike for my mind—something that speeds it through certain tasks, thereby letting it go places previously out of reach. What if it’s actually so detrimental to my mental acuity that I haven’t even noticed my critical faculties withering away? After pondering that worst-case scenario for a while, I calmed down. Yes, consistently opting for the most expedient way to accomplish work rather than the one that produces the best results is no way to live. Sure, being overly reliant on ChatGPT—or any form of generative AI—has its hazards. But I’m pretty confident it’s possible to embrace AI without your reasoning skills atrophying. No single task can represent all the ways people engage with AI, and the one the MIT researchers chose—essay writing—is particularly fraught. The best essays reflect the unique insight of a particular person: When students take the actual SAT for real, they aren’t even allowed to bring a highlighter, let alone a bot. We don’t need EGG helmets to tell us that people who paste ChatGPT’s work into an essay they’ve nominally written have lost out on the learning opportunity presented by grappling with a topic, reaching conclusions, and expressing them for oneself. However, ChatGPT and its LLM brethren also excel at plenty of jobs too mundane to feel guilty about outsourcing. Each week, for example, I ask Anthropic’s Claude to clean up some of the HTML required to produce this newsletter. It handles this scut work faster and more accurately than I can. I’m not sure what my brain waves would reveal, but I’m happy to reinvest any time not spent on production drudgery into more rewarding aspects of my job. Much of the time, AI is most useful not as a solution but a starting point. Almost never would I ask a chatbot about factual information, get an answer, and call it a day. They’re still too error-prone for that. Yet their ease of use makes them an inviting way to get rolling on projects. I think of them as facilitating the research before the old-school research I usually end up doing. And sometimes, AI is a portal into adventures I might otherwise never have taken. So far in 2025, my biggest rabbit hole has been vibe coding—coming up with ideas for apps and then having an LLM craft the necessary software using programming tools I don’t even understand. Being exposed to technologies such as React and TypeScript has left me wanting to learn enough about them to do serious coding on my own. If I do, AI can take credit for sparking that ambition. I’m only so Pollyanna-ish about all this. Over time, the people who see AI as an opportunity to do more thinking—not less of it—

Five years ago, I bought an e-bike. At the time, the motor-equipped two-wheelers were burdened with an iffy reputation. Was it way easier to get up a hill on one than on a bike without a battery? Absolutely. Did that mean people who rode them were lazy or even cheaters? Some cycling enthusiasts thought so.

But what if the boost provided by your e-bike motivated you to make longer trips and more of them—all powered, in part, by your own pedaling? Having logged almost 10,000 miles on my Gazelle, I’m certain it’s been a guilt-free boon to my well-being. Data backs me up.

I thought about that recently while reading about a new study conducted at MIT’s Media Lab. Researchers divided subjects ages 18 to 39 into three groups and had them write essays on topics drawn from the SAT questions answered by college applicants, such as “Do works of art have the power to change people’s lives?” One group relied entirely on unassisted brainpower to complete the essay. A second group could use a search engine. And the third could call on ChatGPT.

The study subjects wore EEG helmets that captured their brain activity as they worked. After analyzing that data, the researchers concluded that access to ChatGPT didn’t just make composing an essay easier. It made it too easy, in ways that might negatively impact people’s long-term ability to think for themselves. In some cases, the ChatGPT users merely cut and pasted text the chatbot had generated; not surprisingly, they exhibited little sense of ownership over the finished product compared to those who didn’t have a computerized ghost on tap.

“Due to the instant availability of the response to almost any question, LLMs can possibly make a learning process feel effortless, and prevent users from attempting any independent problem solving,” the researchers wrote in their report. “By simplifying the process of obtaining answers, LLMs could decrease student motivation to perform independent research and generate solutions. Lack of mental stimulation could lead to a decrease in cognitive development and negatively impact memory.”

The study reached those sobering conclusions in the context of young people growing up in an era of bountiful access to AI. But the alarms it set off also left me worried about the technology’s impact on my own brain. I have long considered AI an e-bike for my mind—something that speeds it through certain tasks, thereby letting it go places previously out of reach. What if it’s actually so detrimental to my mental acuity that I haven’t even noticed my critical faculties withering away?

After pondering that worst-case scenario for a while, I calmed down. Yes, consistently opting for the most expedient way to accomplish work rather than the one that produces the best results is no way to live. Sure, being overly reliant on ChatGPT—or any form of generative AI—has its hazards. But I’m pretty confident it’s possible to embrace AI without your reasoning skills atrophying.

No single task can represent all the ways people engage with AI, and the one the MIT researchers chose—essay writing—is particularly fraught. The best essays reflect the unique insight of a particular person: When students take the actual SAT for real, they aren’t even allowed to bring a highlighter, let alone a bot. We don’t need EGG helmets to tell us that people who paste ChatGPT’s work into an essay they’ve nominally written have lost out on the learning opportunity presented by grappling with a topic, reaching conclusions, and expressing them for oneself.

However, ChatGPT and its LLM brethren also excel at plenty of jobs too mundane to feel guilty about outsourcing. Each week, for example, I ask Anthropic’s Claude to clean up some of the HTML required to produce this newsletter. It handles this scut work faster and more accurately than I can. I’m not sure what my brain waves would reveal, but I’m happy to reinvest any time not spent on production drudgery into more rewarding aspects of my job.

Much of the time, AI is most useful not as a solution but a starting point. Almost never would I ask a chatbot about factual information, get an answer, and call it a day. They’re still too error-prone for that. Yet their ease of use makes them an inviting way to get rolling on projects. I think of them as facilitating the research before the old-school research I usually end up doing.

And sometimes, AI is a portal into adventures I might otherwise never have taken. So far in 2025, my biggest rabbit hole has been vibe coding—coming up with ideas for apps and then having an LLM craft the necessary software using programming tools I don’t even understand. Being exposed to technologies such as React and TypeScript has left me wanting to learn enough about them to do serious coding on my own. If I do, AI can take credit for sparking that ambition.

I’m only so Pollyanna-ish about all this. Over time, the people who see AI as an opportunity to do more thinking—not less of it—could be a lonely minority. If so, the MIT researchers can say “We told you so.”

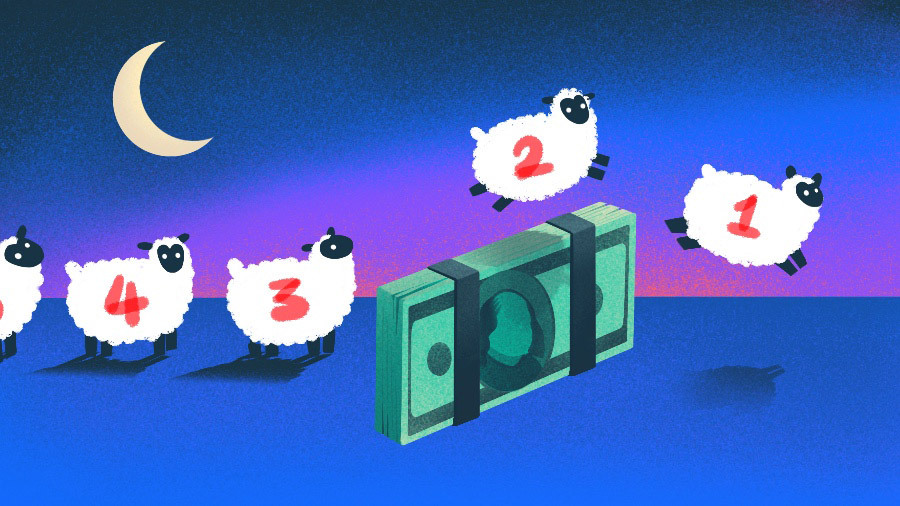

Case in point: At the same time the MIT study was in the news, word broke that VC titan Andreessen Horowitz had invested $15 million in Cluely, a truly dystopian startup whose manifesto boasts its aim of helping people use AI to “cheat at everything” based on the theory that “the future won’t reward effort.” Its origin story involves cofounder and CEO Roy Lee being suspended from Columbia University after developing an app for cheating on technical employment interviews. Which makes me wonder how Lee would feel about his own candidates misleading their way into job offers.

With any luck, the future will turn out to punish Cluely’s cynicism. But the company’s existence—and investors’ willingness to shower it with money—says worse things about humankind than about AI.

You’ve been reading Plugged In, Fast Company’s weekly tech newsletter from me, global technology editor Harry McCracken. If a friend or colleague forwarded this edition to you—or if you’re reading it on FastCompany.com—you can check out previous issues and sign up to get it yourself every Friday morning. I love hearing from you: Ping me at hmccracken@fastcompany.com with your feedback and ideas for future newsletters. I’m also on Bluesky, Mastodon, and Threads, and you can follow Plugged In on Flipboard.

More top tech stories from Fast Company

Meet Delphi, the AI startup that lets experts turn themselves into chatbots

Human beings scale only so far. But using their knowledge to train ‘digital minds’ enables a form of interactive assistance that goes where one-on-one counseling, newsletters, podcasts, and books can’t.

Zillow just turned your real estate doomscrolling into a bedtime habit

Late-night Zillowing gets an upgrade.

Anthropic’s AI copyright ‘win’ is more complicated than it looks

Tech companies are celebrating a major ruling on fair use for AI training, but a closer read shows big legal risks still lie ahead.

BeReal is back. Can it stick around this time?

BeReal is trying to win back users by investing in advertising, primarily on other apps owned by Voodoo Games.

The AI baby boom is here. But can ChatGPT really raise a child?

Parents are using AI for on-demand childcare information. How much is too much?

Nonstop news alerts are driving people to disable their phone notifications

A new report finds rising ‘alert fatigue’ as smartphone users are bombarded with dozens of news notifications each day. Nearly 80% now avoid alerts altogether.

![What Is a Markup Language? [+ 7 Examples]](https://static.semrush.com/blog/uploads/media/82/c8/82c85ebca40c95d539cf4b766c9b98f8/markup-language-sm.png)

![[Weekly funding roundup June 21-27] A sharp rise in VC inflow](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/2/220356402d6d11e9aa979329348d4c3e/Weekly-funding-1741961216560.jpg)