Meet Soot, an explosive new media experience that’s killing the social feed

My daughter is 7 years old, and when she wakes up, the first thing she’ll often do is position herself in the center of an unruly pile of stuff on our basement floor. Construction paper. Tape. Stuffed animals. Pipe cleaners. Markers. Bits of ribbon.To me, it’s the definition of disarray. To her, it puts the creative process in arm’s reach. It provides exactly what she needs to, minutes later, emerge with a charming invention or piece of art. I mention this not only as a proud father, but because it’s the best metaphor I’ve been able to find to describe Soot. Soot is a visual catalog that’s in many ways reminiscent of Pinterest, Behance, or even Instagram. But with $7.7 million in funding, its team is focused less on building the next social network than challenging the status quo of creative UX. Instead of showing just one image or a few images at a time, Soot displays hundreds to thousands of images on your screen at once, allowing you to mainline loosely sorted visual information.[Image: courtesy Soot]Built upon open-source AI and data viz technologies, Soot sorts and organizes images by visual similarity, or by metadata like an artist’s name. The spacing is intentionally organic rather than overly rigid, so that what you’re looking at becomes a resolved shape instead of a grid. And what you’re left with is less a feed or website than it is a digital painter’s palette, or a vast mood board of visual inspiration for you to wade through with your cursor.[Image: courtesy Soot]In this sense, the premise of Soot is perhaps more philosophical than directly practical. “It’s 2025, and we’re still surfing in the vertical linear scroll. [People] look at the feed as the upper limit of what we can do,” says Soot cofounder Jake Harper.Harper believes that the file structures of the Macintosh share the same logic with the scroll of TikTok or Instagram. These are linear organizational views optimized to show you one thing buried under another at a time. The folders and subfolders that inhabit our desktop interfaces force us to inefficiently dig for information and can devolve from discovery to compulsion.“Instead of having information in a scroll, you could see from structures that [pool] like a well that’s not as insidious as the feeds,” he says. “A lot of the negative impact of computers is inherent to the geometries of the interface.”[Image: courtesy Soot]An exploratory interfaceHarper began his career designing as a sound artist with Soundwalk Collective, before making his way to the self-driving car company Zoox (acquired by Amazon) to lead the expression and communication of robotic vehicles. His cofounder, Mary Nally, is the founder of Drop Everything, a creative retreat taking part every two years on the tiny Irish island of Inis Oírr.Soot is organized into invite-only personal spaces, and then everything from the service combines onto a site called Soot World. That includes 4 million pieces of media at the moment, from its 25,000 users in a private beta. Each Soot space can be built from media sourced in all sorts of ways, from direct uploading to copy and pasting URLs from YouTube or a social media account. Monthly subscriptions will be available for individuals, and also companies, as the service scales.But what about the Soot experience itself? A tour through the Guggenheim’s catalog demonstrates how the interface sings. Drag around, and you’ll see the groupings of impressionists like Monet abutting geometrically focused futurists like Gino Severini, before arriving at the dynamic explosions of Wassily Kandinsky. In terms of art history, you can tap into each piece to see its name, year, and provenance, revealing that it’s all a bit of a blender. But zoomed out visually, Soot creates a gradient vibe that just makes sense.[Image: courtesy Soot]“I remember the first time I saw all my own artwork in Soot,” Harper says. “It was like, damn, seeing things from 15 years ago—a rejected student project next to something I made a week ago. It was a really weird experience.” The interface is fascinating in that it demonstrates just how low a lift our single image feeds are in an era when we all have supercomputers in our pockets. The fact that I can mouse over thousands of images through my browser, without my aging Macbook cursing at me through the fan, is a most certain demonstration that our computers are able to do a lot more than we ask of them these days. Zooming in and out in Soot with my trackwheel is instantaneous. And the entire school of images (they do self-organize almost like fish) moves with a satisfying inertia. [Image: courtesy Soot]That said, in my own observations, I found that I was really only focusing on one image at a time. Soot didn’t open some new capacity in my brain. But seeing these interrelated ideas in my peripheral vision still seemed meaningful. And being able to explore a swatch of images in X, Y, and Z space felt more like true exploration than the whims of the algorithm.[Image: courte

My daughter is 7 years old, and when she wakes up, the first thing she’ll often do is position herself in the center of an unruly pile of stuff on our basement floor. Construction paper. Tape. Stuffed animals. Pipe cleaners. Markers. Bits of ribbon.

To me, it’s the definition of disarray. To her, it puts the creative process in arm’s reach. It provides exactly what she needs to, minutes later, emerge with a charming invention or piece of art.

I mention this not only as a proud father, but because it’s the best metaphor I’ve been able to find to describe Soot.

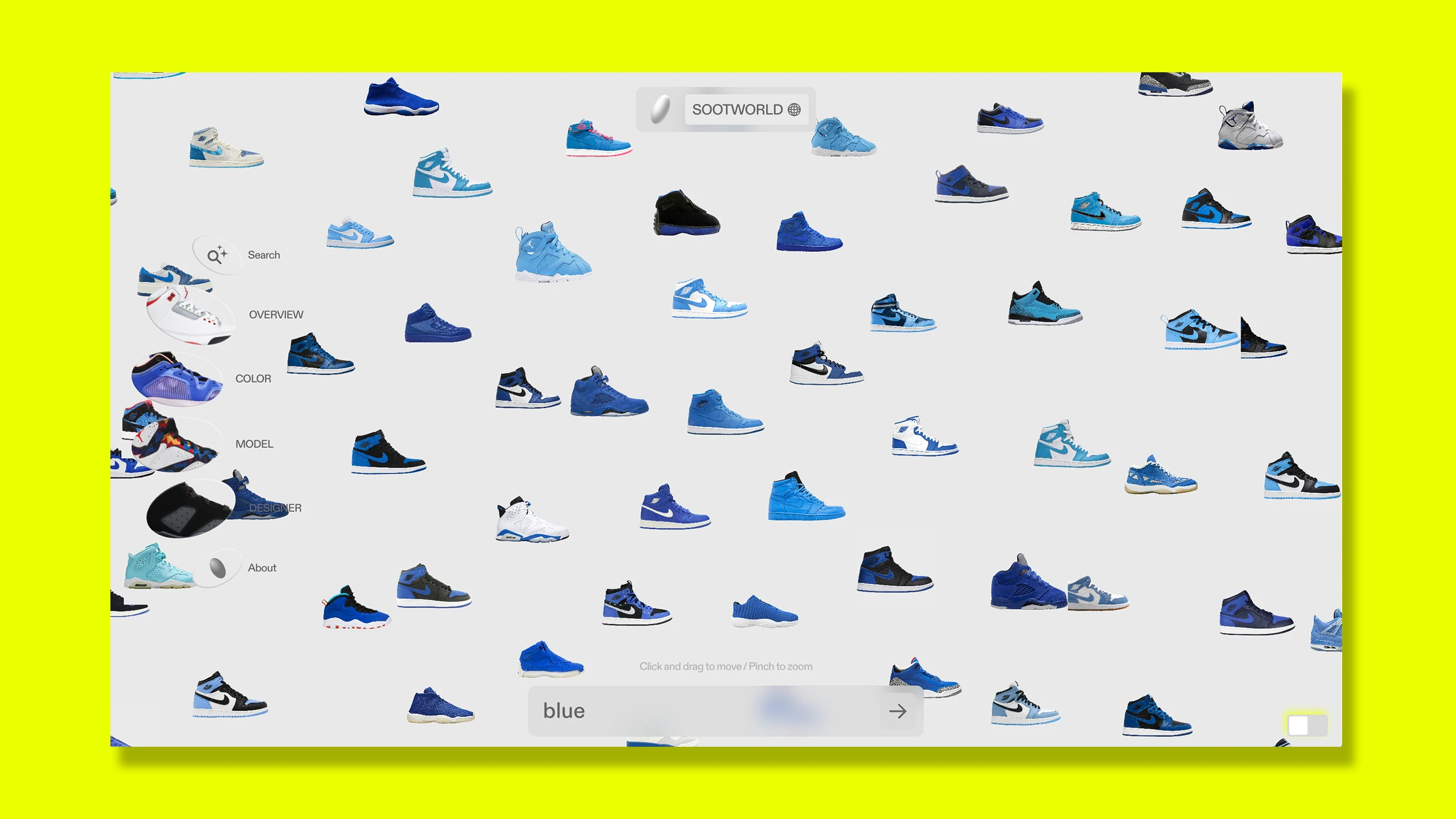

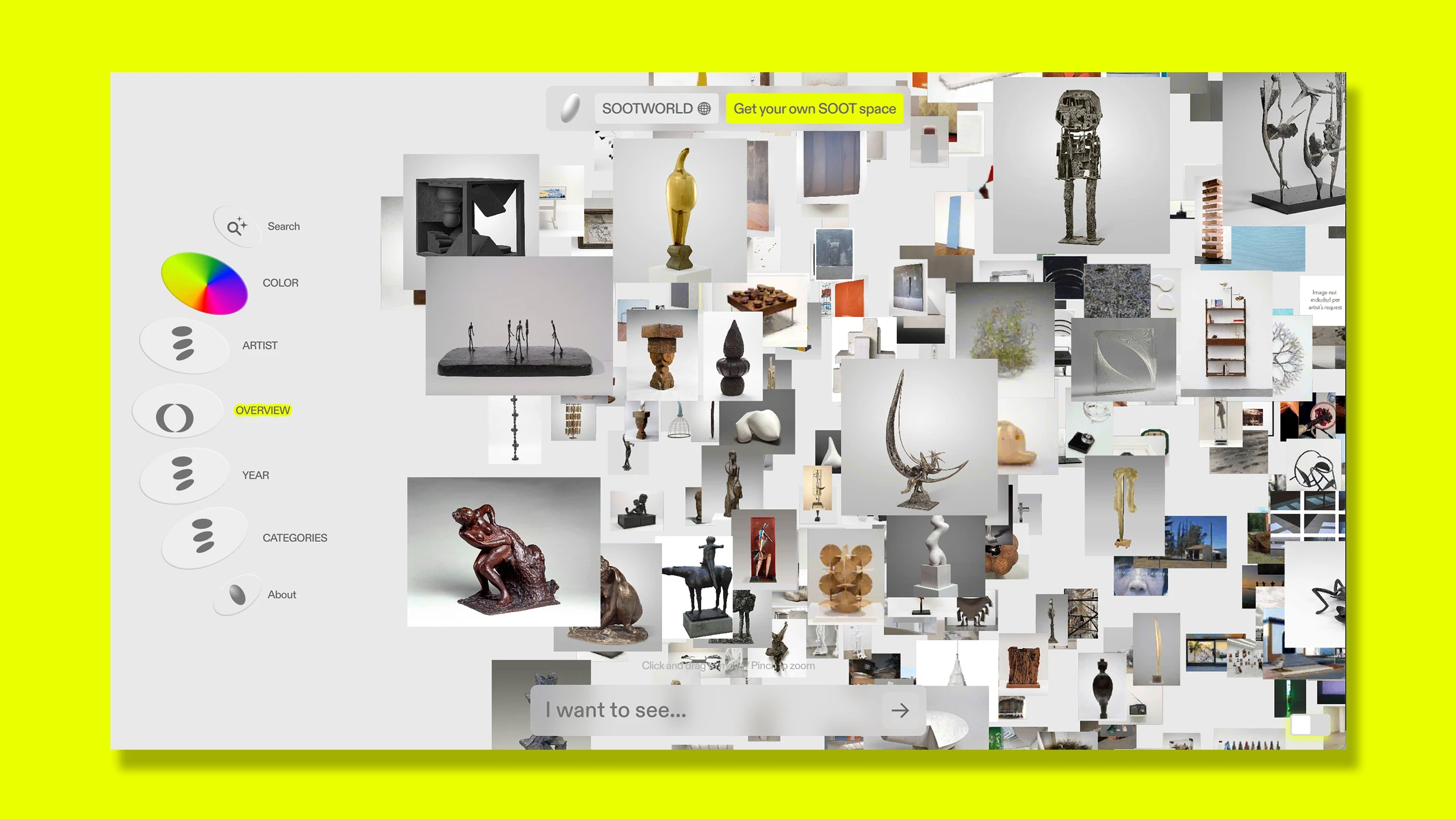

Soot is a visual catalog that’s in many ways reminiscent of Pinterest, Behance, or even Instagram. But with $7.7 million in funding, its team is focused less on building the next social network than challenging the status quo of creative UX. Instead of showing just one image or a few images at a time, Soot displays hundreds to thousands of images on your screen at once, allowing you to mainline loosely sorted visual information.

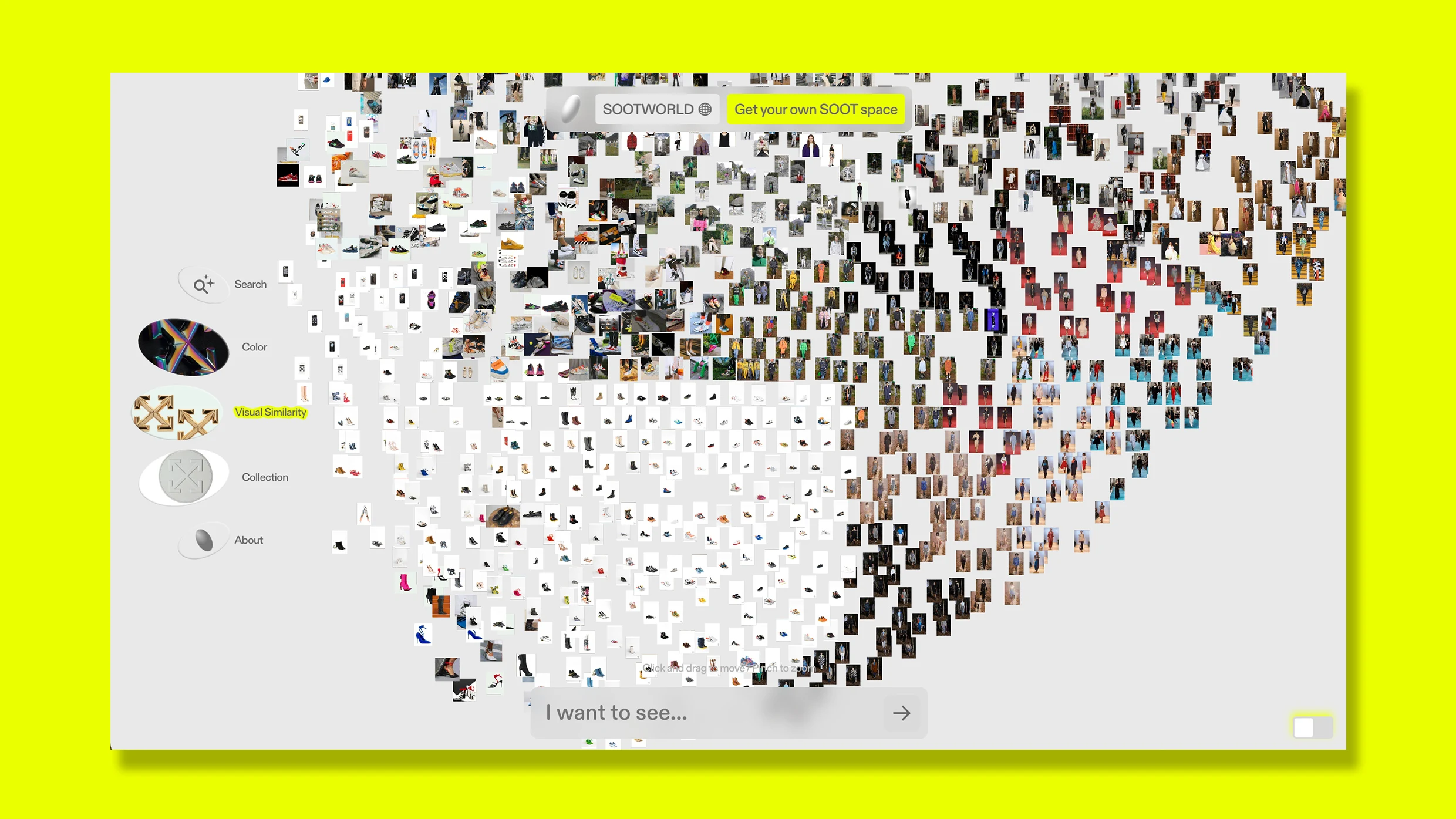

Built upon open-source AI and data viz technologies, Soot sorts and organizes images by visual similarity, or by metadata like an artist’s name. The spacing is intentionally organic rather than overly rigid, so that what you’re looking at becomes a resolved shape instead of a grid. And what you’re left with is less a feed or website than it is a digital painter’s palette, or a vast mood board of visual inspiration for you to wade through with your cursor.

In this sense, the premise of Soot is perhaps more philosophical than directly practical. “It’s 2025, and we’re still surfing in the vertical linear scroll. [People] look at the feed as the upper limit of what we can do,” says Soot cofounder Jake Harper.

Harper believes that the file structures of the Macintosh share the same logic with the scroll of TikTok or Instagram. These are linear organizational views optimized to show you one thing buried under another at a time. The folders and subfolders that inhabit our desktop interfaces force us to inefficiently dig for information and can devolve from discovery to compulsion.

“Instead of having information in a scroll, you could see from structures that [pool] like a well that’s not as insidious as the feeds,” he says. “A lot of the negative impact of computers is inherent to the geometries of the interface.”

An exploratory interface

Harper began his career designing as a sound artist with Soundwalk Collective, before making his way to the self-driving car company Zoox (acquired by Amazon) to lead the expression and communication of robotic vehicles. His cofounder, Mary Nally, is the founder of Drop Everything, a creative retreat taking part every two years on the tiny Irish island of Inis Oírr.

Soot is organized into invite-only personal spaces, and then everything from the service combines onto a site called Soot World. That includes 4 million pieces of media at the moment, from its 25,000 users in a private beta. Each Soot space can be built from media sourced in all sorts of ways, from direct uploading to copy and pasting URLs from YouTube or a social media account. Monthly subscriptions will be available for individuals, and also companies, as the service scales.

But what about the Soot experience itself?

A tour through the Guggenheim’s catalog demonstrates how the interface sings. Drag around, and you’ll see the groupings of impressionists like Monet abutting geometrically focused futurists like Gino Severini, before arriving at the dynamic explosions of Wassily Kandinsky. In terms of art history, you can tap into each piece to see its name, year, and provenance, revealing that it’s all a bit of a blender. But zoomed out visually, Soot creates a gradient vibe that just makes sense.

“I remember the first time I saw all my own artwork in Soot,” Harper says. “It was like, damn, seeing things from 15 years ago—a rejected student project next to something I made a week ago. It was a really weird experience.”

The interface is fascinating in that it demonstrates just how low a lift our single image feeds are in an era when we all have supercomputers in our pockets. The fact that I can mouse over thousands of images through my browser, without my aging Macbook cursing at me through the fan, is a most certain demonstration that our computers are able to do a lot more than we ask of them these days.

Zooming in and out in Soot with my trackwheel is instantaneous. And the entire school of images (they do self-organize almost like fish) moves with a satisfying inertia.

That said, in my own observations, I found that I was really only focusing on one image at a time. Soot didn’t open some new capacity in my brain. But seeing these interrelated ideas in my peripheral vision still seemed meaningful. And being able to explore a swatch of images in X, Y, and Z space felt more like true exploration than the whims of the algorithm.

I am curious to see where Soot goes next, and can only imagine how we might begin to push the norms of UX as ideas like this leave the web browser and entire spaces like VR. I honestly don’t know if the next 20 years of visual interface looks more like this, or more like the conventions in the 20 years we’ve had before. But I do think that, in the era of AI and seemingly limitless processing, we need more experimentation rather than less. We need to stretch what we think might be possible before we settle for what’s worked so far.

“We’re not fully there yet. Right now we’re in our GPT2 era,” says Harper, alluding to the moment before OpenAI went mainstream. “The core users love it, but it’s not ready for mass-market adoption.”

![[Weekly funding roundup May 31-June 6] VC inflow continues to remain stable](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/2/220356402d6d11e9aa979329348d4c3e/WeeklyFundingRoundupNewLogo1-1739546168054.jpg)