WorkWhile, flexible labor platform, raises $23 million Series B

WorkWhile raised a $23 million Series B, Fortune has exclusively learned. Rethink Impact led the round.

At 16, Jarah Euston landed her first job at a Party City—on the better days, as the balloon person.

“It was my first job ever, and I blew up the balloons with the helium,” she said. “But the worst possible job you could have at Party City was called go-backs—take a shopping cart full of tchotchkes that parents didn’t actually want to buy and put them back on the pegboard. You have to find, say, where this Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle goody bag goes, and hang it back up.”

Euston, who grew up in Fresno, Calif, is now the CEO and cofounder of flexible labor platform WorkWhile. The startup, which she founded in 2019 after stints at Yahoo and Nexla, focuses on people working the “frontline,” hourly jobs that she says are the norm in places like Fresno.

“I want to build something for the people I grew up with, the people who work frontline jobs in Fresno,” she told Fortune. “And not just the people in Fresno, but the 80 million Americans working hourly jobs. It’s more than half of the U.S. labor force. And globally, 80% of all workers are working these types of jobs. So, how do we apply technology to improve their situation?”

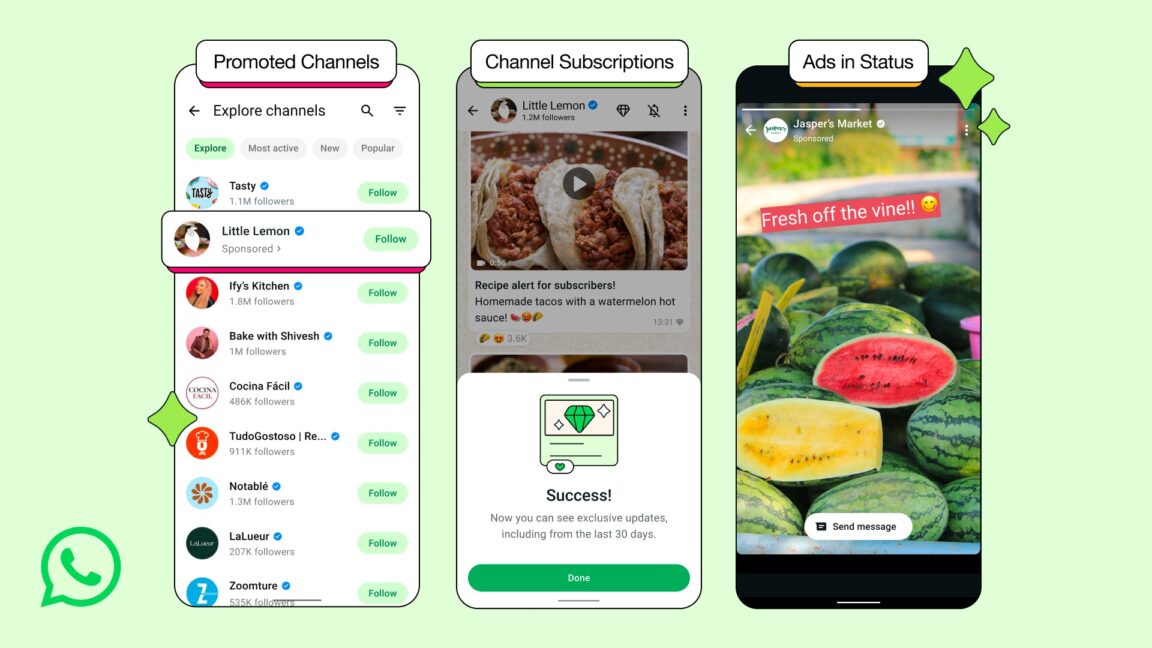

For Euston, part of the solution lay in flexibility—technology that sets up a marketplace where workers can be matched with temporary jobs, adjusting their roles, schedules, and locations to better shape and control their workweek. Six years in, the platform now serves over one million users and employs 63 people.

Now, the startup has raised a $23 million Series B, Fortune has exclusively learned. Rethink Impact led the round, with participation from returning investors Khosla Ventures and Reach Capital. Citi Impact Fund, GingerBread Capital, and Illumen Capital also invested. Simon Khalaf, ex-CEO of fintech Marqeta, also recently joined WorkWhile as COO. The startup has worked with vendors serving Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour, the Super Bowl, NASCAR, the NCAA Final Four, Comic-Con, Edible Arrangements, Thistle, and Worldpac.

WorkWhile’s rise signals that the gig economy is maturing—but many of its long-standing controversies remain. In 2024, the company became tangled in a familiar legal battle for gig companies: it was sued by the San Francisco City Attorney, who alleged WorkWhile had misclassified the workers on its platform as independent contractors, denying them the rights and benefits afforded to employees.

The case is part of the ongoing fallout from California’s Proposition 22, the 2020 ballot initiative that classified most gig workers as independent contractors. In December 2024, WorkWhile agreed to a partial $1 million settlement and committed to reclassifying its non-driver workers as employees. Litigation over the classification of delivery drivers, however, is still ongoing.

“Prop 22 is the law of the land and was upheld by the California Supreme Court, affirming this important right of drivers to work as independent contractors,” Euston added via email. “Our platform users have been very clear with us: they want flexibility. We respect our users’ right to work flexibly and will continue to advocate for it.”

Josh Queenan, a WorkWhile user the company connected me with, said he deeply values the flexibility the platform offers—and that it’s helped him transform his financial life. He told Fortune he earns an extra $5,000 to $6,000 a month, which he puts toward stock investments and is looking to use to buy investment property.

“If I want to cancel a shift, I just give a 24 hour notice, and press the cancel button,” said Queenan. “I have peace of mind, I know that somebody else is going to pick up the shift and that the company we work with isn’t going to be screwed. That’s a huge selling point for WorkWhile.”

For her part, Euston still regularly works shifts via WorkWhile.

“It keeps you up at night, I want to make sure workers on the platform feel they’re the center of WorkWhile,” she said. “That’s why we’re at a startup. The whole point is to help people earn a better living and live better lives. If we don’t put them front and center, that won’t happen. That’s why we try to work shifts.”

So, in some ways Euston’s Party City days are long gone, and in others they’re close—lots of the shifts she works are similar kinds of jobs. With one exception: last year, she took a gig at the Eras Tour last year.

“My job was crowd control,” Euston laughed. “I was telling people ‘you can’t dance on the chairs.’ And as the night went on, the moms got progressively more loosey goosey!”

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com