The Sharpie story: Inside a brand so strong that Starbucks is now depending on it

Mere weeks into his new role as CEO of Starbucks, Brian Niccol joined an earnings call with investors and trumpeted an iconic brand. But it wasn’t Starbucks. “Bringing the Sharpies back to our baristas,” Niccol declared last October, will “give them the opportunity to put that additional human touch on every coffee experience” by writing each customer’s name or an inspiring note on their cup. “We’re tracking down the Sharpies,” Niccol later told CNBC, estimating the company would need about 200,000 of them. The comments drew attention—Starbucks even followed up with a TV ad featuring baristas jotting on cups—but in a way, they revealed more about Sharpie than they did about the coffee giant. Sharpie defines a category. It’s simultaneously universal and personal, instantly recognizable, and ubiquitous. It’s such a strong brand, in fact, that Starbucks, a global juggernaut with a market cap of more than $100 billion, is in effect leaning on it for support. Yet when the CNBC hosts mused that maybe it was time to go long on whoever makes Sharpies, they weren’t certain which company that was—3M, maybe?—until they looked it up. It’s Newell Brands, the Atlanta-based conglomerate behind Rubbermaid, Mr. Coffee, and Oster appliances. Sharpie is part of a suite of “learning and development” brands that includes Paper Mate, Elmer’s, Expo, and Prismacolor, which is the company’s most profitable division, says Kris Malkoski, the segment’s CEO. Nobody at Sharpie knew the Starbucks announcement was coming. “We were totally psyched!” says Gina Lázaro, vice president of brand marketing for Newell’s writing segment, who recalls being bombarded with congratulatory messages from within the company and without. Newell CEO Chris Peterson even reached out to Niccol to say thanks. The real significance to Sharpie wasn’t the wholesale order. A five-pack of Sharpies runs about $5 at Walmart; at that price, 200,000 markers would work out to $200,000, not exactly a game changer for a company like Newell, with 2024 revenue of $7.6 billion. It was the free, and highly complimentary, publicity. “It’s amazing when a fantastic brand calls out your brand by name,” Lázaro says. [Photo: Heami Lee; prop stylist: Christine Keely] Not that Sharpie doesn’t market itself. Newell advertises the marker brand’s vast spectrum of products and colors across digital and social media, in stores, and at events such as SXSW and Comic-Con. And the brand promptly chimed in on Instagram to amplify Starbucks’s endorsement; it also sent its promotional Sharpie Bus to a nearby Starbucks in Atlanta to give out markers. But Sharpie, like a crafty Zelig, just has a way of quietly turning up. Artists rely on the markers. Actors and athletes sign autographs with them. Their scent has inspired perfume (“Love the smell of permanent markers?” reads the marketing copy for “Sharpie,” by Wicked Good) and candles. Stephen Colbert has made a running gag of sniffing them. When President Trump drew on a map to offer his unsubstantiated take on a hurricane’s potential path, well, that became #sharpiegate. Trump, who uses Sharpies for all official business and has boasted about having them custom-made, isn’t even the first president to endorse Sharpie: George W. Bush was a fan, too. With its familiar script logo and unflashy form factor, Sharpie’s core attribute is “dependability,” says Paola Antonelli, senior architecture and design curator and director of research and development at the Museum of Modern Art. “You can trust a Sharpie to do exactly what it says it’ll do, without trying to wow you with any special effects,” she says, distilling its appeal into three words: “Consistent, definitive, indelible.” Dependability might not be the sexiest brand attribute, but it sure seems to work. The company says that it has sold an estimated 21 billion Sharpie markers worldwide over the past 60 years, and nearly five billion over the past decade alone. In a 2024 survey commissioned by the brand, respondents said they owned, on average, about seven Sharpies, and that at any given moment there was one within 10 feet. Three in four said that the markers made them more creative. [Photo: Sharpie] “It sits right in the middle of that Venn diagram of office supply and art supply,” says Austin Kleon, the artist and writer of illustrated books such as the New York Times bestseller Steal Like an Artist. “I’ve joked for years that I use them because you can steal them from any office supply cabinet.” It’s been about 40,000 years since our ancestors figured out how to leave expressive marks on cave walls, kicking off centuries of design and technology improvements in tools for handmade communication. Ballpoint pens, first patented in 1888, became the epitome of a mass writing tool. The felt-tip, introduced in 1910, had more versatility. A “permanent” version, the Magic Marker—which used quick-drying ink that worked on glass, metal, and plastic—was invented

Mere weeks into his new role as CEO of Starbucks, Brian Niccol joined an earnings call with investors and trumpeted an iconic brand. But it wasn’t Starbucks.

“Bringing the Sharpies back to our baristas,” Niccol declared last October, will “give them the opportunity to put that additional human touch on every coffee experience” by writing each customer’s name or an inspiring note on their cup. “We’re tracking down the Sharpies,” Niccol later told CNBC, estimating the company would need about 200,000 of them.

The comments drew attention—Starbucks even followed up with a TV ad featuring baristas jotting on cups—but in a way, they revealed more about Sharpie than they did about the coffee giant. Sharpie defines a category. It’s simultaneously universal and personal, instantly recognizable, and ubiquitous. It’s such a strong brand, in fact, that Starbucks, a global juggernaut with a market cap of more than $100 billion, is in effect leaning on it for support.

Yet when the CNBC hosts mused that maybe it was time to go long on whoever makes Sharpies, they weren’t certain which company that was—3M, maybe?—until they looked it up. It’s Newell Brands, the Atlanta-based conglomerate behind Rubbermaid, Mr. Coffee, and Oster appliances. Sharpie is part of a suite of “learning and development” brands that includes Paper Mate, Elmer’s, Expo, and Prismacolor, which is the company’s most profitable division, says Kris Malkoski, the segment’s CEO.

Nobody at Sharpie knew the Starbucks announcement was coming. “We were totally psyched!” says Gina Lázaro, vice president of brand marketing for Newell’s writing segment, who recalls being bombarded with congratulatory messages from within the company and without. Newell CEO Chris Peterson even reached out to Niccol to say thanks.

The real significance to Sharpie wasn’t the wholesale order. A five-pack of Sharpies runs about $5 at Walmart; at that price, 200,000 markers would work out to $200,000, not exactly a game changer for a company like Newell, with 2024 revenue of $7.6 billion. It was the free, and highly complimentary, publicity. “It’s amazing when a fantastic brand calls out your brand by name,” Lázaro says.

Not that Sharpie doesn’t market itself. Newell advertises the marker brand’s vast spectrum of products and colors across digital and social media, in stores, and at events such as SXSW and Comic-Con. And the brand promptly chimed in on Instagram to amplify Starbucks’s endorsement; it also sent its promotional Sharpie Bus to a nearby Starbucks in Atlanta to give out markers.

But Sharpie, like a crafty Zelig, just has a way of quietly turning up. Artists rely on the markers. Actors and athletes sign autographs with them. Their scent has inspired perfume (“Love the smell of permanent markers?” reads the marketing copy for “Sharpie,” by Wicked Good) and candles. Stephen Colbert has made a running gag of sniffing them. When President Trump drew on a map to offer his unsubstantiated take on a hurricane’s potential path, well, that became #sharpiegate. Trump, who uses Sharpies for all official business and has boasted about having them custom-made, isn’t even the first president to endorse Sharpie: George W. Bush was a fan, too.

With its familiar script logo and unflashy form factor, Sharpie’s core attribute is “dependability,” says Paola Antonelli, senior architecture and design curator and director of research and development at the Museum of Modern Art. “You can trust a Sharpie to do exactly what it says it’ll do, without trying to wow you with any special effects,” she says, distilling its appeal into three words: “Consistent, definitive, indelible.”

Dependability might not be the sexiest brand attribute, but it sure seems to work. The company says that it has sold an estimated 21 billion Sharpie markers worldwide over the past 60 years, and nearly five billion over the past decade alone. In a 2024 survey commissioned by the brand, respondents said they owned, on average, about seven Sharpies, and that at any given moment there was one within 10 feet. Three in four said that the markers made them more creative.

“It sits right in the middle of that Venn diagram of office supply and art supply,” says Austin Kleon, the artist and writer of illustrated books such as the New York Times bestseller Steal Like an Artist. “I’ve joked for years that I use them because you can steal them from any office supply cabinet.”

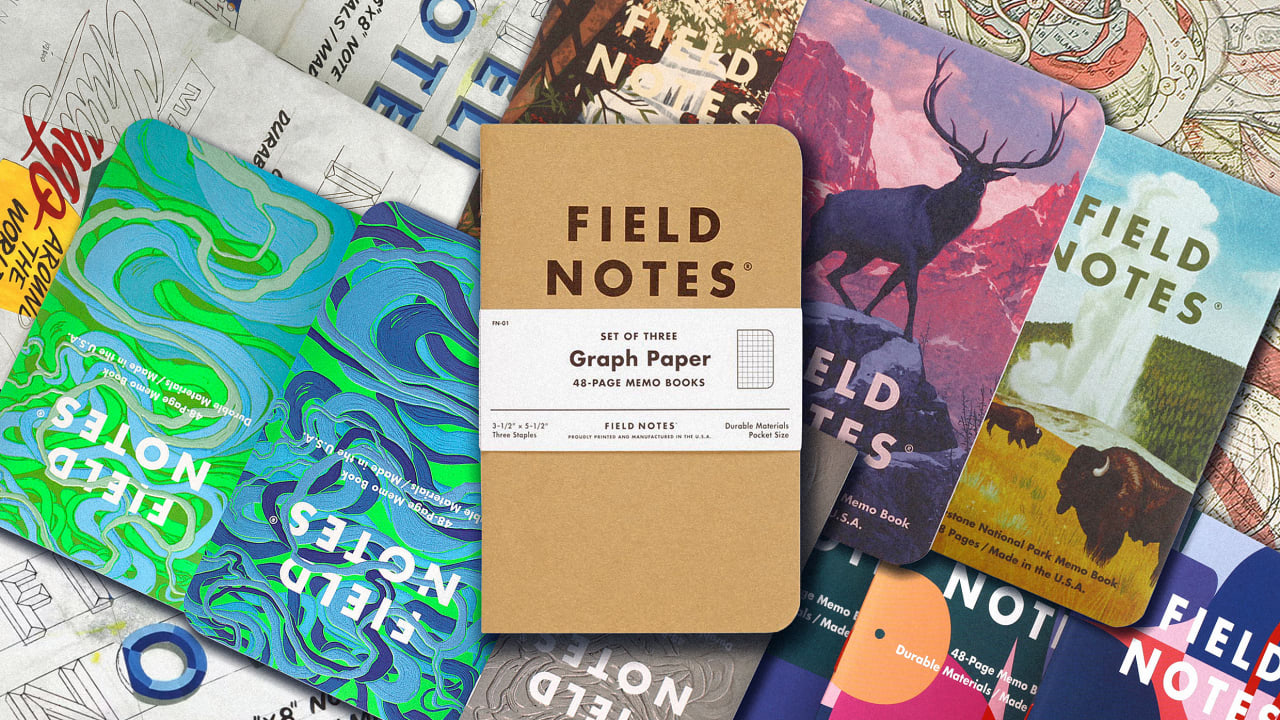

It’s been about 40,000 years since our ancestors figured out how to leave expressive marks on cave walls, kicking off centuries of design and technology improvements in tools for handmade communication. Ballpoint pens, first patented in 1888, became the epitome of a mass writing tool. The felt-tip, introduced in 1910, had more versatility. A “permanent” version, the Magic Marker—which used quick-drying ink that worked on glass, metal, and plastic—was invented by entrepreneur Sidney Rosenthal in 1952. It proved popular both on the factory floor and in the kitchen drawer. But its fat tip yielded much cruder marks than a regular pen, limiting its use. It took a nearly century-old American company to figure out a solution.

Sanford Ink Co. started out in 1857 as an ink and glue manufacturer in Worcester, Massachusetts. It moved to Chicago, narrowed its focus, and became a successful ink manufacturer—Norman Rockwell illustrated an ad marking its 70th birthday in 1927. But by the 1960s, the market for ink for fountain pens was dwindling, leading Sanford to create its own writing instrument. The first-ever “pen style” permanent marker, with a slimmer barrel and a tip made from extruded acrylic fibers that came to a sharp point, debuted in 1964. It was called the Sharpie Fine Point.

In a precocious influencer-courting move, Sharpie sent some markers to Johnny Carson, who loved them and mentioned them on The Tonight Show. This, according to Sharpie lore, evolved into a sponsorship with NBC and endorsements from such other personalities as Jack Paar and Hugh Downs.

It wasn’t until the 1990s that Sharpie’s story got colorful again, after Newell acquired Sanford in 1992. Newell absorbed Sharpie and the dry-erase marker brand Expo, then smartly decided to expand the Sharpie line when big-box retailers like Staples and Office Depot were on the ascent.

Five new Sharpie marker styles debuted between 1997 and 2002, along with the first new colors in decades, including aqua, berry, turquoise, and lime. The brand’s first TV campaign aired in the late 1990s, emphasizing the many ways to use a Sharpie. Small packaging tweaks allowed the product to fit into a range of retail settings; Sharpie ended up everywhere from Costco to Tractor Supply Co. to Blick Art Materials. Sharpie started making self-expression part of its core brand message.

At the same time, the brand owed a good piece of its growth to a parallel phenomenon that probably wasn’t in its business plan: the rise of celebrity culture and the memorabilia market. Sharpie became “an essential part” of autograph signings, notes Sharpie’s Lázaro. The markers work on jerseys, footballs, baseballs, and bats, making them “the writing instrument of choice” for fan interaction, she says. The company introduced the Sharpie Autograph Pen in 1992—“the first and only made just for getting and giving autographs.”

Connecting the Sharpie to autograph seeking did the brand a favor, creating a link between an everyday quotidian tool that sits in a kitchen drawer or supply closet and something more rarefied and aspirational. The association with sports stars, in particular, emerged as a primary Sharpie branding strategy. The company lined up endorsement deals and ads with golfer Arnold Palmer, Nascar drivers including Kurt Busch, and, later, soccer superstar David Beckham. The brand currently promotes a “Rookie of the Year” initiative, highlighting top college football players poised to Sharpie-sign more autographs and NFL contracts.

But the moments that gave Sharpie its biggest brand boosts continued to be those in which it was an accessory in someone else’s spotlight. A memorable example: San Francisco 49ers star receiver Terrell Owens catching a touchdown pass in 2002—then pulling a Sharpie from his sock, signing the ball, and handing it to his financial adviser in the stands. The stunt prompted the NFL to institute a rule against players bringing “foreign objects” onto the field. It became a legendary end-zone celebration, with Sharpie playing a discrete yet vital role.

More recently, Sharpie has highlighted its connection to another constituency: creators. Its most recent new products, S-Gel pens and water-based paint pens called Sharpie Creative Markers, are aimed explicitly at this cohort. As part of its “World Is Your Canvas” campaign, the brand recruited Reddit cofounder Alexis Ohanian and Blavity cofounder Morgan DeBaun in 2023 to promote the S-Gel pens; last year, the Sharpie Bus visited New York’s Gov Ball, San Diego Comic-Con, Miami’s Art Basel, and other festivals, giving out hundreds of packs of Creative Markers to help people “uncap creativity.”

Sharpie’s creative audience has been core to its success all along. Timothy Goodman, an artist and designer, and author of the graphic memoir I Always Think It’s Forever, remembers adopting the Sharpie largely because there were just a lot of them around. But he says that the decisiveness of a permanent marker fit well with his playful, there-are-no-mistakes style, and he used Sharpie paint pens to create a mural for the Ace Hotel in New York that gave his early career a boost; later, he published the book Sharpie Art Workshop, full of Sharpie-centric projects by him and other artists.

Artists are picky consumers, finicky about their tools (Goodman’s work these days involves thicker-nibbed Molotow paint markers and Montana markers and spray paint). Yet for many, that classic Sharpie becomes a mainstay. Portland, Oregon–based artist Jason Sturgill started using one while working as a designer at Nike. It’s “ridiculous,” he says, “how many tools I have in this space, and I still just have a bucket of Sharpies and that’s kind of my go-to. My drawing is very simple—I try to not have a lot of detail. So it’s easy for me to wield.”

Kate Bingaman-Burt, an artist and professor of graphic design at Portland State University, uses Sharpies for zine-making workshops, where “that confident line” emboldens students—and photocopies well. For many, the flagship Sharpie functions as a gateway drug, leading to an interest in a wider range of creative tools that, increasingly, Sharpie itself provides. (Bingaman-Burt is a fan of the new Creative Markers.)

In “design thinking” workshops, Allan Chochinov, founder of the School of Visual Arts’ Products of Design program, distributes classic Sharpies and Post-it Notes, because the combination of those two tools—an unforgiving marker and limited space to mark—forces action and concision. “It’s like permission,” he says. “It frees you up to not worry about your skills” and still get on with the messy and imperfect process of creating.

Which isn’t to say that every idea will be a gem, let alone every autograph, executive order—or personalized coffee-cup message. Starbucks really did order a “significant” number of Sharpies, says Lázaro, though she declines to say whether it was actually 200,000, and in Starbucks’s earnings call in late January, CEO Niccol cited the company’s reintroduction of “handwritten notes on cups to better connect with customers” as a pillar of the company’s effort to “reestablish Starbucks as the community coffeehouse.”

That said, sales at Starbucks are still down year over year, and some of its customers reportedly find the mandated return of the “human touch”—via written names and well wishes—to feel a bit forced, even cringey. You can’t blame the Sharpie Fine Point marker for that. It may be a powerful tool, but what it expresses is still up to the user.