Shopify just killed UX design

Carl Rivera believes that in the artificial intelligence era, we don’t need the “UX” in UX designer. Last week, Rivera, chief design officer at Shopify, dropped the title at the e-commerce company, along with the title of content designer. His public announcement was met with some kudos and quite a bit of disagreement. “When I put it out online, you get a complete view of how the market looks and feels about change,” he says. “How our jobs and how work is changing in the AI era of technology is both extremely exciting, but it’s also so frightening.” For Rivera, dropping UX from job titles is about empowering humans in the face of AI. Instead of using his team to implement best UX practices, he’s asking them to lean in to what makes their skills unique: taste and intuition. “I want to get away from terms that make our craft more science than art. AI enables anyone to make things usable. Our job is to make them unforgettable,” Rivera said in his announcement. Scientists and engineers codified “user experience” as a discipline in the mid-’80s and ’90s after the success of the graphical user interface ushered in by the Macintosh. Since then, UX has developed predictable and replicable best practices—many of which have been consumed and replicated by AI at this point. Rivera argues that UX, as a discipline, has become a bounded box created to standardize the experience of technology. UX designers use these rules and play within that safe zone “because it feels good to quantify things,” he says. But he believes those same rules also push other people in the organization away from the creative process. The result of the current system are user experiences that rate, according to Rivera, a “7 out of 10.” They tick all the boxes, but they are ultimately forgettable. We just dropped UX as a title at @Shopify. Same for Content Design. If you design, you're a Designer. If you write, you're now a Writer. Simpler. Better. (1/3)— Carl Rivera (@postcarl) June 6, 2025 Shopify’s solution is to get rid of the UX moniker altogether, instead focusing on the human skills that can make a user experience extraordinary—not just good enough. To Rivera, taste, intuition, and breaking the rules might be humans’ last bastion in this age of cookie-cutter AI. “When things become so scientific, they don’t have a soul. You see that a product is well designed and it’s doing the things that it’s supposed to do, but there’s nothing about the product that you’re able to fall in love [with]. Because it’s exactly the thing it was supposed to be,” Rivera says. He believes his team’s job at Shopify is to create software that people want to come back to, time and time again—and only humans are capable of that. There was no UX science for those who invented UX I believe Rivera is right. Many of the leading minds behind the personal computing revolution didn’t think about experience through the lens of user experience design. People like Andy Hertzfeld, the chief software architect of the Macintosh, and Susan Kare, who was responsible for the Mac’s icons, crafted the experience through a vision to create the extraordinary. They didn’t call themselves UX designers, because at that point, the term didn’t exist. It was only later, after the Mac came out, that others codified what the original UX designers learned through intuition at Apple’s Human Interface Group (HIG). In the late ’80s, and especially in the ’90s, there was an explosion in the science of usability, led by people like Joy Mountford—who was brought in by Steve Jobs to start the HIG in 1986—and Jakob Nielsen and Don Norman—who made a business out of it with the Nielsen Norman Group, a consulting company for usability and UX certification in the ’90s. These scientists observed the outcome of human intuition and used focus groups, cameras tracking user motion, and quantitative and qualitative measurements to turn gut feelings (“Oh this feels good! That makes sense! This is fun! That sucks! Let’s go this way!”) generated by the Mac team into the science of UX. It was a necessary advancement at the time. But now we’re in a new technological age where all of that hard work and knowledge has been vacuumed up and processed, effectively becoming a textbook for AI. Now, it’s time for a new age of creative thinking. How does this look in real life? “We’ve been working on this change inside of the design team since I took over as CDO, and it really comes from this point of view I have that, in this new era of technology all of us are basically a 7-out-of-10 at every job in the market,” Rivera says. Rivera found that, if he looked at his team’s job descriptions and titles, so much of it was about how we try to turn subjective and aesthetic professions—like design and writing—into a science. “Everything is much easier when you’re, like, ‘Oh, the good is measurable.’ But what if that is not a fact, and it’s the opposite?” he asks. “What if we’re here to

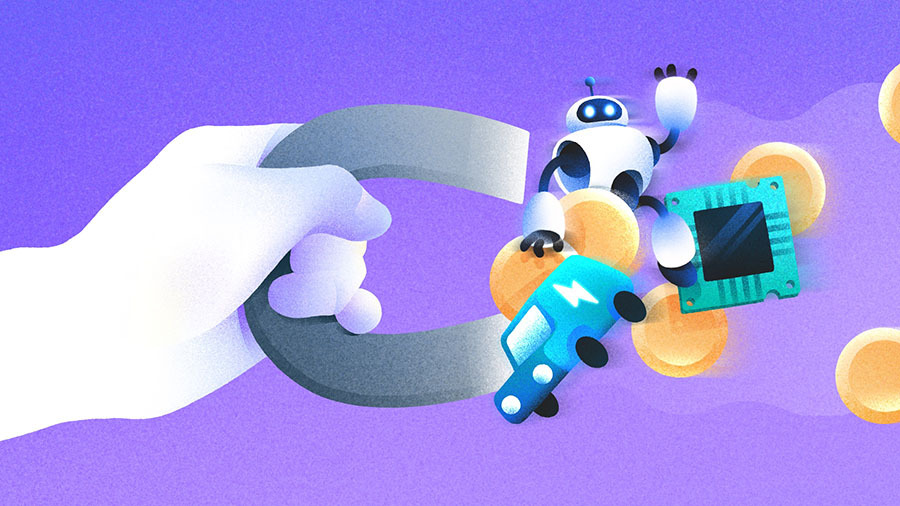

Carl Rivera believes that in the artificial intelligence era, we don’t need the “UX” in UX designer. Last week, Rivera, chief design officer at Shopify, dropped the title at the e-commerce company, along with the title of content designer.

His public announcement was met with some kudos and quite a bit of disagreement. “When I put it out online, you get a complete view of how the market looks and feels about change,” he says. “How our jobs and how work is changing in the AI era of technology is both extremely exciting, but it’s also so frightening.”

For Rivera, dropping UX from job titles is about empowering humans in the face of AI. Instead of using his team to implement best UX practices, he’s asking them to lean in to what makes their skills unique: taste and intuition. “I want to get away from terms that make our craft more science than art. AI enables anyone to make things usable. Our job is to make them unforgettable,” Rivera said in his announcement.

Scientists and engineers codified “user experience” as a discipline in the mid-’80s and ’90s after the success of the graphical user interface ushered in by the Macintosh. Since then, UX has developed predictable and replicable best practices—many of which have been consumed and replicated by AI at this point. Rivera argues that UX, as a discipline, has become a bounded box created to standardize the experience of technology. UX designers use these rules and play within that safe zone “because it feels good to quantify things,” he says.

But he believes those same rules also push other people in the organization away from the creative process. The result of the current system are user experiences that rate, according to Rivera, a “7 out of 10.” They tick all the boxes, but they are ultimately forgettable.

Shopify’s solution is to get rid of the UX moniker altogether, instead focusing on the human skills that can make a user experience extraordinary—not just good enough. To Rivera, taste, intuition, and breaking the rules might be humans’ last bastion in this age of cookie-cutter AI.

“When things become so scientific, they don’t have a soul. You see that a product is well designed and it’s doing the things that it’s supposed to do, but there’s nothing about the product that you’re able to fall in love [with]. Because it’s exactly the thing it was supposed to be,” Rivera says.

He believes his team’s job at Shopify is to create software that people want to come back to, time and time again—and only humans are capable of that.

There was no UX science for those who invented UX

I believe Rivera is right. Many of the leading minds behind the personal computing revolution didn’t think about experience through the lens of user experience design. People like Andy Hertzfeld, the chief software architect of the Macintosh, and Susan Kare, who was responsible for the Mac’s icons, crafted the experience through a vision to create the extraordinary. They didn’t call themselves UX designers, because at that point, the term didn’t exist. It was only later, after the Mac came out, that others codified what the original UX designers learned through intuition at Apple’s Human Interface Group (HIG).

In the late ’80s, and especially in the ’90s, there was an explosion in the science of usability, led by people like Joy Mountford—who was brought in by Steve Jobs to start the HIG in 1986—and Jakob Nielsen and Don Norman—who made a business out of it with the Nielsen Norman Group, a consulting company for usability and UX certification in the ’90s.

These scientists observed the outcome of human intuition and used focus groups, cameras tracking user motion, and quantitative and qualitative measurements to turn gut feelings (“Oh this feels good! That makes sense! This is fun! That sucks! Let’s go this way!”) generated by the Mac team into the science of UX. It was a necessary advancement at the time. But now we’re in a new technological age where all of that hard work and knowledge has been vacuumed up and processed, effectively becoming a textbook for AI. Now, it’s time for a new age of creative thinking.

How does this look in real life?

“We’ve been working on this change inside of the design team since I took over as CDO, and it really comes from this point of view I have that, in this new era of technology all of us are basically a 7-out-of-10 at every job in the market,” Rivera says.

Rivera found that, if he looked at his team’s job descriptions and titles, so much of it was about how we try to turn subjective and aesthetic professions—like design and writing—into a science.

“Everything is much easier when you’re, like, ‘Oh, the good is measurable.’ But what if that is not a fact, and it’s the opposite?” he asks. “What if we’re here to do this thing that’s intrinsically subjective, that’s unmeasurable?”

Dropping the UX from titles, Rivera says, is meant to get away from the idea that a job is a science, and back to the basics, where people can create truly special experiences. He believes that now, thanks to AI, good UX is something that is democratic and can belong to everyone in the organization. “But really great design, I think, is something that we uniquely hold and, as such, as designers, we are here to do,” he says.

Within Shopify, the reception has been overwhelmingly positive. Rivera believes that this is because, internally, the company has already come quite far on its journey of internalizing its shift toward a more AI-centric workplace where the technology can (and will) assume some of the rote tasks once given to human designers.

“It prompted a lot of great conversations, too,” he says. “Like, okay, if our job is changing this way, how does it change how I do my job and the craft that I need to hone? How do you hone and improve taste, or bring a point of view?”

Not everyone agrees with Rivera. While many UX designers have applauded his move, some believe it is a mistake. “Titles aren’t just labels. They reflect focus, craft, and expertise,” someone replied to him on X. Rivera argues the compression in the industry has been happening long before this point. UX, UI, and prototyping were all different jobs before AI started to shuffle things around.

Now designers can craft the entire story, from vision to execution. For Shopify, this is an opportunity, not a threat. Creativity and intuition are humans’ last bastion against the standardization enabled by AI. “If we’re heading into unknown territory,” Rivera says, “I can’t think of a better group to draw up a version of what this future can look like, and to explore the edges of technology and what is possible.”

![X Highlights Back-To-School Marketing Opportunities [Infographic]](https://imgproxy.divecdn.com/dM1TxaOzbLu_kb9YjLpd7P_E_B_FkFsuKp2uSGPS5i8/g:ce/rs:fit:770:435/Z3M6Ly9kaXZlc2l0ZS1zdG9yYWdlL2RpdmVpbWFnZS94X2JhY2tfdG9fc2Nob29sMi5wbmc=.webp)