Innovative parks aren’t just bold urban design—they lower the temperature in cities

Cities, and those who live in them, are clamoring for more green space, and the benefits parks, trees, and recreation areas provide. The Trust for Public Land’s annual ParkScore report found nearly a quarter of Americans in the 100 largest cities don’t live within a 10-minute walk of a park or greenspace. While few cities have acres and acres of space to transform into parkland, they do have opportunities to create new types of urban parks, such as elevated parks, pocket parks fashioned from vacant lots, rails-to-trails projects or capping highways to create new greenspaces. New research, including exclusive project analysis for Fast Company, finds that these projects have a significant cooling impact, showcasing how these kinds of infrastructure interventions can provide some of the densest parts of urban America with much-needed cooling. A study conducted by Climate Central on behalf of the High Line found that New York City’s iconic linear park offers unique cooling and shading benefits, in addition to the social and environmental benefits of adding parkspace. High Line, NYC [Photo: Max Harlynking/Unsplash] “We always had a suspicion that we can also make our community more healthier and livable, and we wanted data around it,” says Alan van Capelle, Executive Director of Friends of the High Line, Researchers started by tracking the urban heat island intensity (UHII) of the areas surrounding the High Line in Manhattan. This measurement captures the additional heat created in urban environments by buildings and pavement, as well as density. Some neighborhoods near the High Line exhibited a 12.9°F UHII, among the highest temperatures Climate Central has found after analyzing 65 U.S. cities. But the park–via the obvious shading impact from the structure itself, but even more importantly, from the additional shading, transpiration and overall cooling benefits of so many additional trees and plants–cut the UHII to just 4.7°F along many stretches of the park, creating an eight degree cooling impact. There was variance along the High Line, with areas that are primarily rocks and shrub exhibiting a less pronounced cooling impact, underscoring how it’s not just shading that makes the difference. And it’s not exactly news that parks provide cooling benefits to cities. But evidence that adaptive reuse parks in the midst of cities can achieve such pronounced temperature differences suggest that they can be an important tool for urban cooling. High Line, NYC [Photo: Polina Rytova/Unsplash Climate Central found that other such parks exhibit similar impacts. In exclusive research for Fast Company, Jennifer Brady, senior data analyst for Climate Central, applied existing data and research to a number of newer urban parks across the country and found similar cooling impacts. Chicago’s 606, an elevated rails-to-trails project on the city’s near northwest side, may cool the adjacent neighborhoods 6°F to 8°F, depending on the precise build type and density. Klyde Warren Park in Dallas, which caps a highway adjacent to downtown and runs through one of the city’s hottest neighborhoods, yields approximately 4°F to 6°F cooler temperatures. The Lafitte Greenway in New Orleans and Railroad Park in Birmingham, Alabama, both located in relatively cooler parts of their respective cities, still cool adjoining areas by 4°F. Chicago, 606 Trail [Photo: Shep McAllister/Unsplash The design of these parks–including shade structures, shading impact with bridges and overhangs, and of course plants and tree cover–can make a big difference, said Brady. It also helps that much of this kind of abandoned industrial infrastructure–composed of cement and old buildings–adds to the heat, so simply removing them reduces urban heat gain. But it also shows that targeting particular dense areas with the most pronounced heat island effect can be done, and make a dramatic change. There’s always been a strong case to transform vacant lots and leftover lots in areas without park access, both from a recreation and health angle as well as public safety. Adding cooling and climate resilience to the list should make an even stronger case for more investment in these kinds of industrial reuse park projects. Klyde Warren Park, Dallas. [Photo: TrongNguyen/iStock Editorial/Getty Images Plus] Last year, the nation’s 100 largest cities invested a record $12.2 billion in parks; steering more of that funding towards these types of projects can have serious resilience impacts in an era of heightened climate change. Van Capelle said there’s currently 49 other such reuse park projects taking place across North America that are part of the High Line Network, an advocacy group for these kinds of greenspace projects. He sees the heat island mitigation impact as just another reason to advocate for and invest in these projects. “Being able to step out of your apartment and go into a cool location, being able to know

Cities, and those who live in them, are clamoring for more green space, and the benefits parks, trees, and recreation areas provide. The Trust for Public Land’s annual ParkScore report found nearly a quarter of Americans in the 100 largest cities don’t live within a 10-minute walk of a park or greenspace.

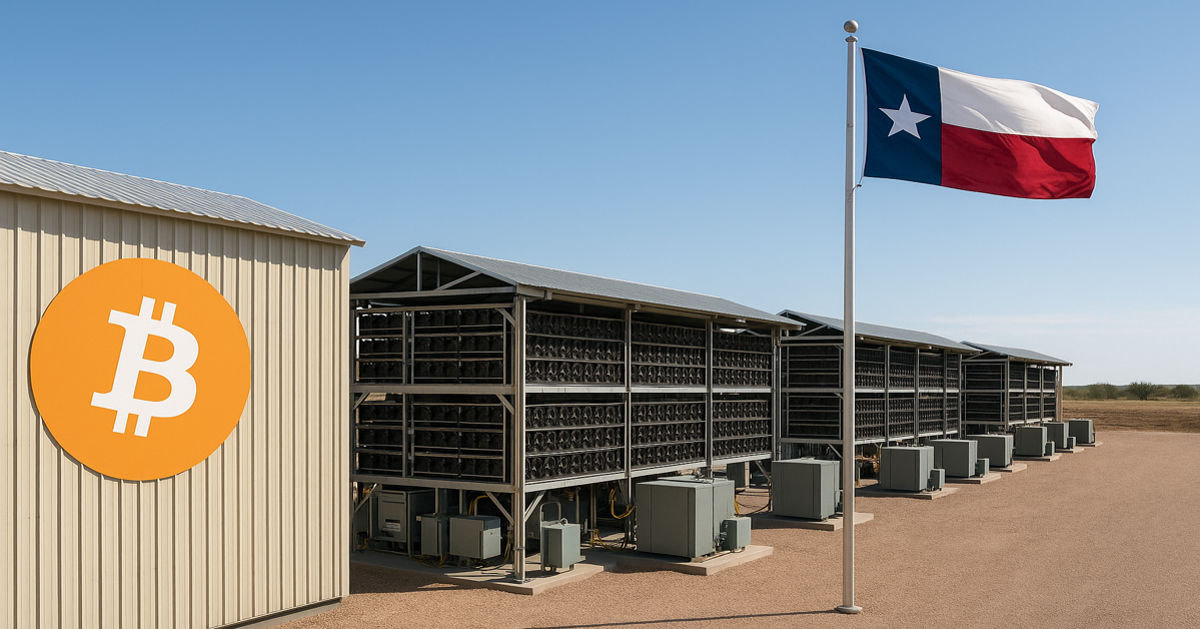

While few cities have acres and acres of space to transform into parkland, they do have opportunities to create new types of urban parks, such as elevated parks, pocket parks fashioned from vacant lots, rails-to-trails projects or capping highways to create new greenspaces. New research, including exclusive project analysis for Fast Company, finds that these projects have a significant cooling impact, showcasing how these kinds of infrastructure interventions can provide some of the densest parts of urban America with much-needed cooling.

A study conducted by Climate Central on behalf of the High Line found that New York City’s iconic linear park offers unique cooling and shading benefits, in addition to the social and environmental benefits of adding parkspace.

“We always had a suspicion that we can also make our community more healthier and livable, and we wanted data around it,” says Alan van Capelle, Executive Director of Friends of the High Line,

Researchers started by tracking the urban heat island intensity (UHII) of the areas surrounding the High Line in Manhattan. This measurement captures the additional heat created in urban environments by buildings and pavement, as well as density. Some neighborhoods near the High Line exhibited a 12.9°F UHII, among the highest temperatures Climate Central has found after analyzing 65 U.S. cities.

But the park–via the obvious shading impact from the structure itself, but even more importantly, from the additional shading, transpiration and overall cooling benefits of so many additional trees and plants–cut the UHII to just 4.7°F along many stretches of the park, creating an eight degree cooling impact.

There was variance along the High Line, with areas that are primarily rocks and shrub exhibiting a less pronounced cooling impact, underscoring how it’s not just shading that makes the difference. And it’s not exactly news that parks provide cooling benefits to cities. But evidence that adaptive reuse parks in the midst of cities can achieve such pronounced temperature differences suggest that they can be an important tool for urban cooling.

Climate Central found that other such parks exhibit similar impacts. In exclusive research for Fast Company, Jennifer Brady, senior data analyst for Climate Central, applied existing data and research to a number of newer urban parks across the country and found similar cooling impacts.

Chicago’s 606, an elevated rails-to-trails project on the city’s near northwest side, may cool the adjacent neighborhoods 6°F to 8°F, depending on the precise build type and density. Klyde Warren Park in Dallas, which caps a highway adjacent to downtown and runs through one of the city’s hottest neighborhoods, yields approximately 4°F to 6°F cooler temperatures.

The Lafitte Greenway in New Orleans and Railroad Park in Birmingham, Alabama, both located in relatively cooler parts of their respective cities, still cool adjoining areas by 4°F.

The design of these parks–including shade structures, shading impact with bridges and overhangs, and of course plants and tree cover–can make a big difference, said Brady. It also helps that much of this kind of abandoned industrial infrastructure–composed of cement and old buildings–adds to the heat, so simply removing them reduces urban heat gain.

But it also shows that targeting particular dense areas with the most pronounced heat island effect can be done, and make a dramatic change. There’s always been a strong case to transform vacant lots and leftover lots in areas without park access, both from a recreation and health angle as well as public safety. Adding cooling and climate resilience to the list should make an even stronger case for more investment in these kinds of industrial reuse park projects.

Last year, the nation’s 100 largest cities invested a record $12.2 billion in parks; steering more of that funding towards these types of projects can have serious resilience impacts in an era of heightened climate change.

Van Capelle said there’s currently 49 other such reuse park projects taking place across North America that are part of the High Line Network, an advocacy group for these kinds of greenspace projects. He sees the heat island mitigation impact as just another reason to advocate for and invest in these projects.

“Being able to step out of your apartment and go into a cool location, being able to know that in the summertime, when the city can become uncomfortable, there’s a place like the High Line that runs along a number of neighborhoods is vitally important,” said van Capelle.

![Is ChatGPT Catching Google on Search Activity? [Infographic]](https://imgproxy.divecdn.com/RMnjJQs1A7VQFmqv9plBlcUp_5Xhm4P_hzsniPsfHiU/g:ce/rs:fit:770:435/Z3M6Ly9kaXZlc2l0ZS1zdG9yYWdlL2RpdmVpbWFnZS9kYWlseV9zZWFyY2hlc19pbmZvZ3JhcGhpYzIucG5n.webp)