AI companies are throwing big money at newly-minted PhDs, sparking fears of an academic ‘brain drain’

This is possibly problematic for academia.

Larry Birnbaum, a professor of computer science at Northwestern University was recruiting a promising PhD to become a graduate researcher. Simultaneously, Google was wooing the student. And when he visited the tech giant’s campus in Mountain View, California, the company slated him to chat with its cofounder and CEO Sergey Brin and Sundar Pichai, who are collectively worth about $140 billion and command over 183,000 employees.

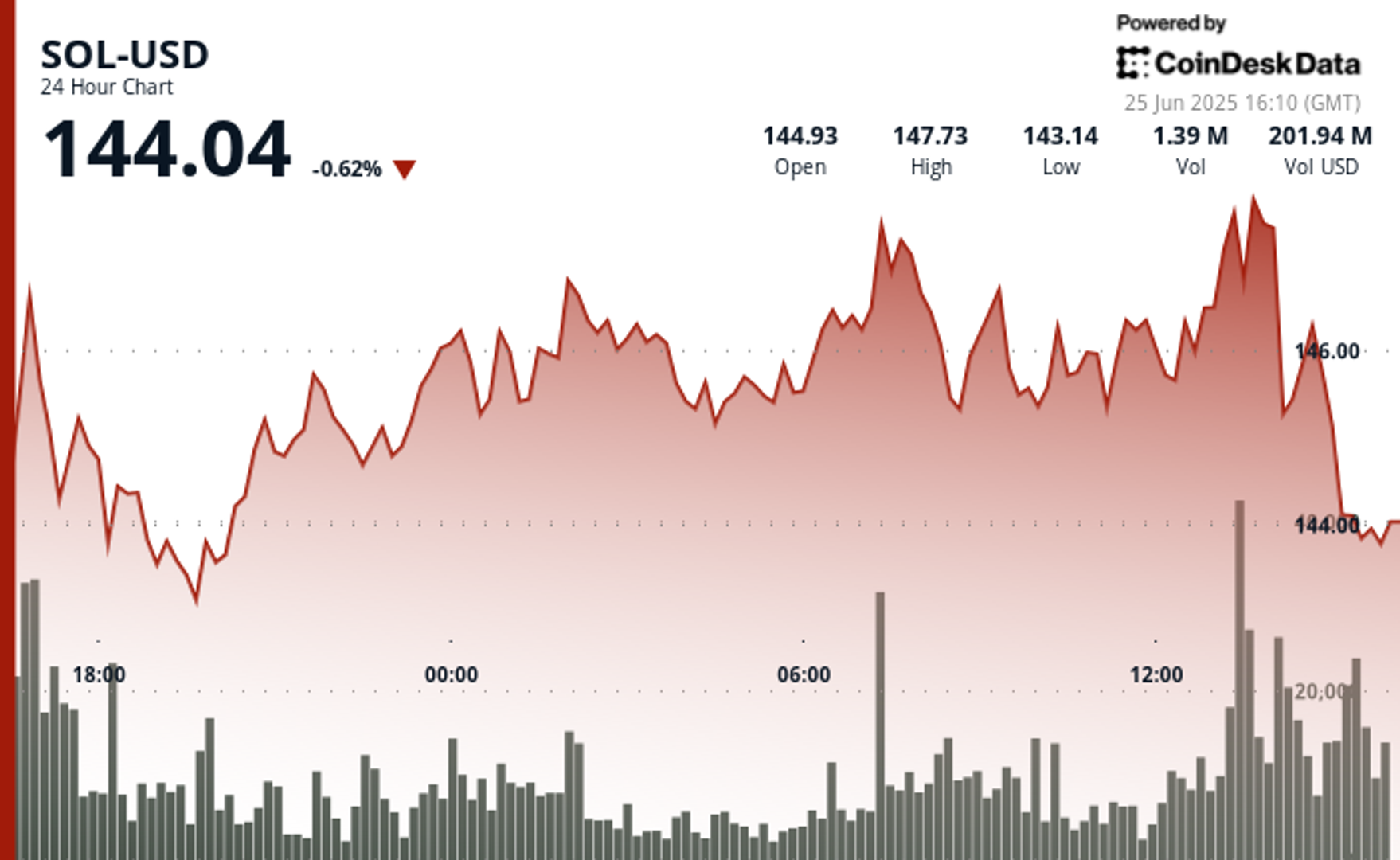

“How are we going to compete with that?” Birnbaum asks, noting that PhDs in corporate research roles can make as much as five-times professorial salaries, which average $155,000 annually. “That’s the environment that every chair of computer science has to cope with right now.”

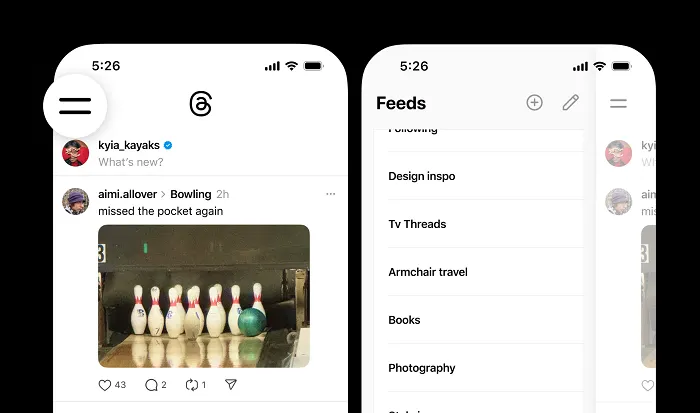

Though Birnbaum says these recruitment scenarios have been “happening for a while,” the phenomena has reportedly worsened as salaries across the industry have been sky-rocketing. The trend recently became headline news after reports surfaced of Meta offering to pay some highly-experienced AI researchers between seven- and nine-figure salaries. Those offers—coupled with the strong demand for leaders to propel AI applications—may be helping to pull up the salary levels of even newly-minted PhDs. Even though some of these graduates have no professional experience, they are being offered the types of comma-filled levels traditionally reserved for director- and executive-level talent.

Some academics fear a ‘brain drain’

Engineering professors and department chairs at Johns Hopkins, University of Chicago, Northwestern and New York York University interviewed by Fortune are divided on whether these lucrative offers lead to a “brain drain” from academic labs.

The brain drain camp believes this phenomena depletes the ranks of academic AI departments, which still do important research and which also are responsible for training the next generation of PhD students. At the private labs, the AI researchers help juice big tech’s bottom line while providing, in these critics’ view, no public benefit. The unconcerned argue that academia is a thriving component of this booming labor market.

Anasse Bari, a professor of computer science and director of the predictive analytics and AI research lab at New York University, says that the corporate opportunities available to AI-focused academics is “significantly” affecting academia. “My general theory is that If we want a responsible future for AI, we must first invest in a solid AI education that upholds these values, cultivating thoughtful AI practitioners, researchers, and educators who will carry this mission forward,” he wrote to Fortune via email, emphasizing that despite receiving “many” offers for industry-side work, his NYU commitments take precedence.

In the days before ChatGPT, top AI researchers were in high-demand, just as today. But many of the top corporate AI labs, such as OpenAI, Google DeepMind, and Meta’s FAIR (Fundamental AI Research), would allow established academics to keep their university appointments, at least part-time. This would allow them to continue to teach and train graduate students, while also conducting research for the tech companies.

While some professors say that there’s been no change to how frequently corporate labs and universities are able to reach these dual corporate-academic appointments, others disagree. NYU’s Bari says this model has declined due to “intense talent competition, with companies offering over millions of dollars for full-time commitment which outpaces university resources and shifts focus to proprietary innovation.”

Commitment to their faculty appointments remained true for all academics Fortune interviewed for this story. But professors like Henry Hoffman, who chairs the University of Chicago’s Department of Computer Science, has watched his PhD students get courted by tech companies since he began his professorship in 2013.

“The biggest thing to me is the salaries,” he says. He mentions a star student with zero professional experience who recently dropped out of the UChicago PhD program to accept a “high six-figure” offer from ByteDance. “When students can get the kind of job they want [as students], there’s no reason to force them to keep going.”

While PhDs thrive, undergard computer science grads struggle

The job market for computer science and engineering PhDs who study AI is a stark contrast to the one faced by undergraduate computer engineers. This degree-level polarization exists because many of those with bachelor degrees in computer science would traditionally find jobs as coders. But LLMs are now writing large portions of code at many companies, including Microsoft and Salesforce. Meanwhile, most AI-relevant PhD students have their pick of frothy jobs–in academia, tech and finance. These graduates are courted by the private sector because their training propels AI and machine learning applications, which, in turn, can increase revenue opportunities for model makers.

There were 4,854 people who graduated with AI-relevant PhDs in mathematics and computer science, per year across U.S. universities, according to 2022 data. This number has increased significantly–by about 20%–since 2014. These PhDs’ post-graduate employment rate is greater than those graduating with bachelor degrees in similar fields. And in 2023, 70% of AI-relevant PhDs took private sector jobs post-grad, a huge increase from two decades ago when just 20% of these grads accepted corporate work, per MIT.

Make no mistake: PhDs in AI, computer science, applied mathematics and related fields have always had lucrative opportunities available after graduation. Until now, one of the most financially-rewarding paths was quantitative research at hedge funds: all-in compensation for PhDs fresh out of school can climb to $1 million-plus in these roles. It’s a compelling pitch, especially for students who’ve spent up to seven years living off meager stipends of about $40,000 a year.

The all-but-assured path to prosperity has made relevant PhD programs in computer science and math extremely popular. AI and machine learning are the most popular disciplines among engineering PhDs, according to a 2023 Computing Research Association survey. UChicago computer science department chair Hoffman says that PhD admissions applications have surged by about 12% in the last few years alone, pressuring him and his colleagues to hire new faculty to increase enrollment and meet the demand.

Applications to AI PhD programs are on the rise

Though Trump’s federal funding cuts to universities have significant impacts on research in many departments, they may be less pertinent to those working on AI-related projects. This is partially because some of this research is funded by corporations. Google, for example, is collaborating with the University of Chicago to research trustworthy AI.

That dichotomy probably underscores Johns Hopkins University’s decision to open its Data Science and AI Institute: a $2 billion five-year effort to enroll 750 PhD students in engineering disciplines and hire over 100 new tenure-track faculty members, making it one of the largest PhD programs in the country.

“Despite the dreary mood elsewhere, the AI and data science area at Hopkins is rosy,” says Anton Dahbura, the executive director of Johns Hopkins’ Information Security Institute and co-director of Institute for Assured Autonomy, likely referring to his University’s cut of 2,000 workers after it lost $800 million in federal funding earlier this year. Dahbura supports this argument by noting that Hopkins received “hundreds” of applications for professor positions in its Data Science and AI Institute.

For some, the reasons to remain in academia are ethical.

Luís Amaral, a computer science professor at Northwestern, is “really concerned” that AI companies have overhyped the capabilities of their large language models and that their strategies will breed catastrophic societal implications, including environmental destruction. He says about OpenAI leadership, “If I’m a smart person, I actually know how bad the team was.”

Because most corporate labs are largely focused on LLM- and transformer-based approaches, if these methods ultimately fall short of the hype, there could be a reckoning for the industry. “Academic labs are among the few places actively exploring alternative AI architectures beyond LLMs and transformers,” says NYU’s Bari, who is researching creative applications for AI using a model based on birds’ intelligence. “In this corporate-dominated landscape, academia’s role as a hub for non-mainstream experimentation has likely become more important.”

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com

![What Is a Markup Language? [+ 7 Examples]](https://static.semrush.com/blog/uploads/media/82/c8/82c85ebca40c95d539cf4b766c9b98f8/markup-language-sm.png)