This startup wants to make more climate-friendly metal in the US

A California-based company called Magrathea just turned on a new electrolyzer that can make magnesium metal from seawater. The technology has the potential to produce the material, which is used in vehicles and defense applications, with net-zero greenhouse-gas emissions. Magnesium is an incredibly light metal, and it’s used for parts in cars and planes, as…

A California-based company called Magrathea just turned on a new electrolyzer that can make magnesium metal from seawater. The technology has the potential to produce the material, which is used in vehicles and defense applications, with net-zero greenhouse-gas emissions.

Magnesium is an incredibly light metal, and it’s used for parts in cars and planes, as well as in aluminum alloys like those in vehicles. The metal is also used in defense and industrial applications, including the production processes for steel and titanium.

Today, China dominates production of magnesium, and the most common method generates a lot of the emissions that cause climate change. If Magrathea can scale up its process, it could help provide an alternative source of the metal and clean up industries that rely on it, including automotive manufacturing.

The star of Magrathea’s process is an electrolyzer, a device that uses electricity to split a material into its constituent elements. Using an electrolyzer in magnesium production isn’t new, but Magrathea’s approach represents an update. “We really modernized it and brought it into the 21st century,” says Alex Grant, Magrathea’s cofounder and CEO.

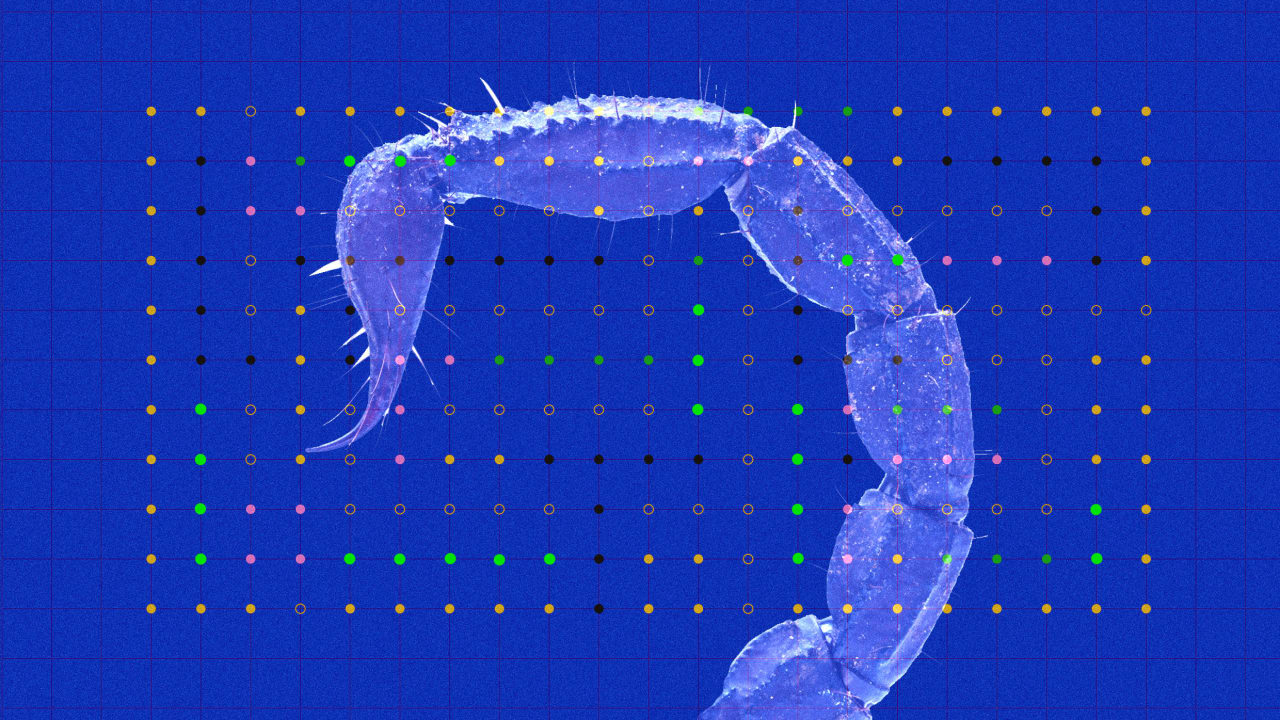

The whole process starts with salty water. There are small amounts of magnesium in seawater, as well as in salt lakes and groundwater. (In seawater, the concentration is about 1,300 parts per million, so magnesium makes up about 0.1% of seawater by weight.) If you take that seawater or brine and clean it up, concentrate it, and dry it out, you get a solid magnesium chloride salt.

Magrathea takes that salt (which it currently buys from Cargill) and puts it into the electrolyzer. The device reaches temperatures of about 700 °C (almost 1,300 °F) and runs electricity through the molten salt to split the magnesium from the chlorine, forming magnesium metal.

Typically, running an electrolyzer in this process would require a steady source of electricity. The temperature is generally kept just high enough to maintain the salt in a molten state. Allowing it to cool down too much would allow it to solidify, messing up the process and potentially damaging the equipment. Heating it up more than necessary would just waste energy.

Magrathea’s approach builds in flexibility. Basically, the company runs its electrolyzer about 100 °C higher than is necessary to keep the molten salt a liquid. It then uses the extra heat in inventive ways, including to dry out the magnesium salt that eventually goes into the reactor. This preparation can be done intermittently, so the company can take in electricity when it’s cheaper or when more renewables are available, cutting costs and emissions. In addition, the process will make a co-product, called magnesium oxide, that can be used to trap carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, helping to cancel out the remaining carbon pollution.

The result could be a production process with net-zero emissions, according to an independent life cycle assessment completed in January. While it likely won’t reach this bar at first, the potential is there for a much more climate-friendly process than what’s used in the industry today, Grant says.

Breaking into magnesium production won’t be simple, says Simon Jowitt, director of the Nevada Bureau of Mines and of the Center for Research in Economic Geology at the University of Nevada, Reno.

China produces roughly 95% of the global supply as of 2024, according to data from the US Geological Survey. This dominant position means companies there can flood the market with cheap metal, making it difficult for others to compete. “The economics of all this is uncertain,” Jowitt says.

The US has some trade protections in place, including an anti-dumping duty, but newer players with alternative processes can still face obstacles. US Magnesium, a company based in Utah, was the only company making magnesium in the US in recent years, but it shut down production in 2022 after equipment failures and a history of environmental concerns.

Magrathea plans to start building a demonstration plant in Utah in late 2025 or early 2026, which will have a capacity of roughly 1,000 tons per year and should be running in 2027. In February the company announced that it signed an agreement with a major automaker, though it declined to share its name on the record. The automaker pre-purchased material from the demonstration plant and will incorporate it into existing products.

After the demonstration plant is running, the next step would be to build a commercial plant with a larger capacity of around 50,000 tons annually.