Government borrowing binge could crowd out mortgages and business investment

U.S. Treasuries accounted for $28.3 trillion, or roughly 60%, of the country’s $46.9 trillion fixed-income market last year.

- Private investment could suffer as investors increasingly allocate funds to finance the government rather than firms and consumers, Apollo chief economist Torsten Sløk has warned. This phenomenon, known as crowding out, could become a bigger problem as the cost of servicing the $37 trillion national debt increases.

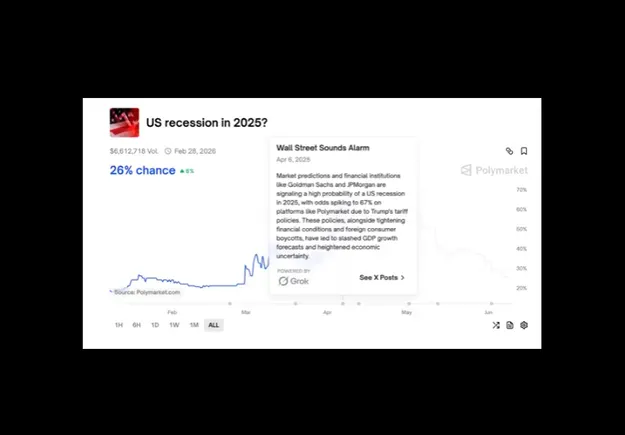

Wall Street seems increasingly antsy about how a ballooning federal deficit could weigh on both companies and consumers.

As the national debt grows faster, so does the pace of government borrowing—which could start to dominate credit markets. U.S. Treasuries accounted for $28.3 trillion, or roughly 60%, of the country’s $46.9 trillion fixed-income market at the end of 2024, according to the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association. Some believe the government binge is now competing with private companies and consumers for available dollars to borrow.

“This is not healthy,” Torsten Sløk, chief economist at private equity giant Apollo Global Management, wrote in a note on Sunday. “Half of credit issued in the economy should not be going to the government.”

That’s because private investment could suffer, Sløk explained, as investors allocate more and more of their funds to finance the government rather than firms and consumers. Borrowing costs rise with less loanable funds to go around, a phenomenon termed “crowding out.”

“The bottom line is that if the level of government debt were significantly lower,” Sløk wrote, “more dollars would be available for consumers to buy new cars and new houses, and for companies to build new factories.”

Jay Hatfield, the CEO of Infrastructure Capital Advisors, estimates this will reduce U.S. gross domestic product by $300 billion, or just over 1% of total GDP, based on the nearly $2 trillion deficit and assuming a 15% return on corporate investment after taxes.

“Deficit spending always crowds out private investment and hurts economic growth,” Hatfield, who manages ETFs and a series of hedge funds, told Fortune in a text message. “Particularly since it is impossible to cut politically post-[2008] recession as we have seen after the pandemic.”

Others aren’t sure if that is visible just yet. Corporate borrowing continues to grow at a fast pace, Matt Sheridan, lead portfolio manager of income strategies at AllianceBernstein, told Fortune. Mortgage lending has been sideways over the past five years, but that’s because homeowners don’t want to refinance at higher interest rates, not because banks don’t want to give them loans.

“We’re not seeing a lot of stress yet,” Sheridan said, “but it might be early days.”

Avoiding a ‘debt death spiral’

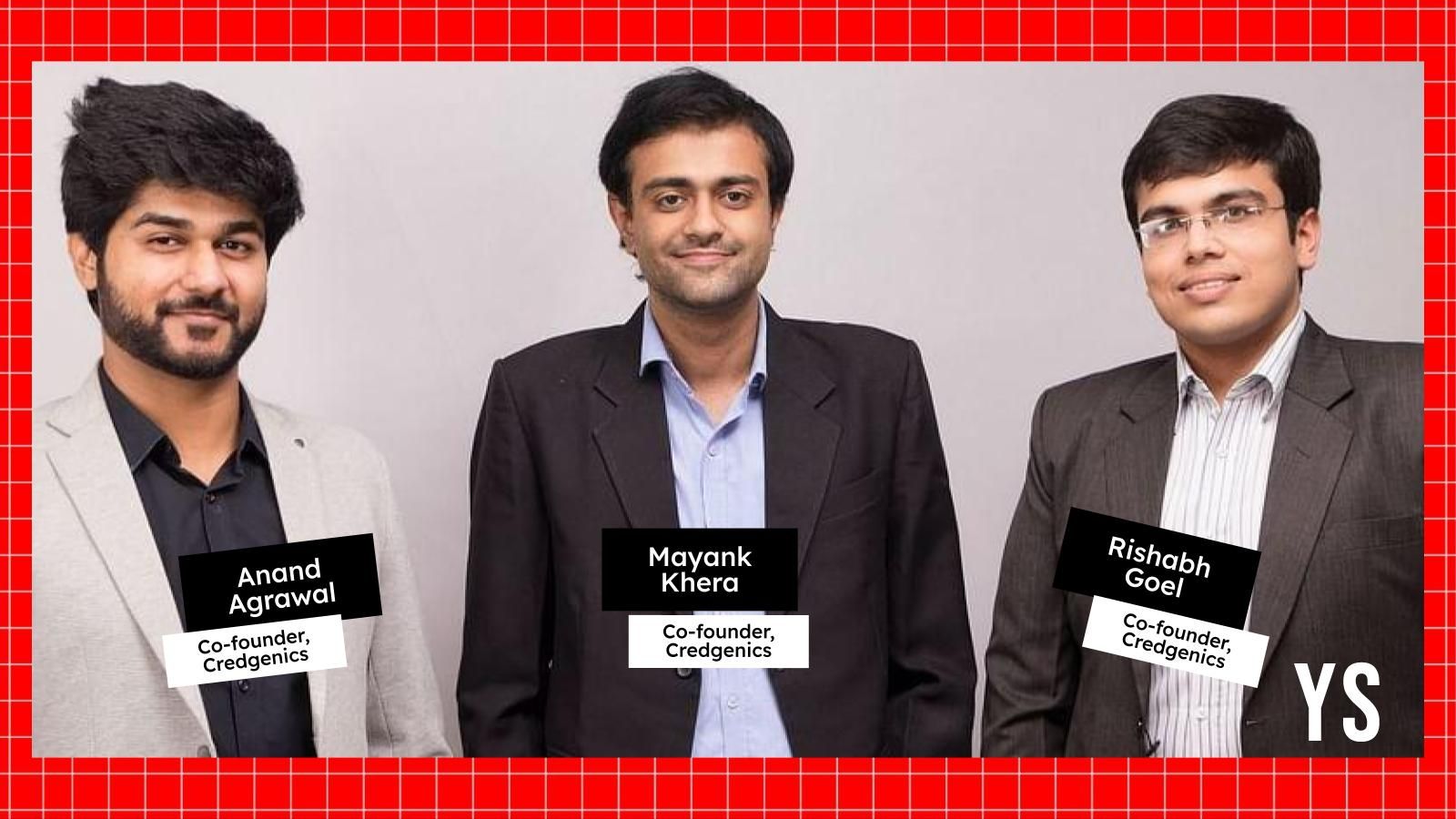

Few in finance, of course, are probably more famous for sounding the debt alarm than Ray Dalio. The billionaire founder of Bridgewater Associates, the world’s largest hedge fund, has long warned about the increasing costs of servicing the $37 trillion national debt.

Interest payments on the debt will crack $1 trillion this year, according to the Committee for a Responsible Budget, and only trails Social Security as a share of government spending.

As these payments get larger, it increasingly crowds out productive spending, Dalio recently told Fortune’s Diane Brady. Meanwhile, interest rates are pushed higher, weighing on markets and the economy, or the government “prints money” and buys debt to pay its bills, which causes inflation.

“You get both the central government and the central bank creating debt to pay for debt and you begin a spiral,” he said. “There are no easy answers.”

Recent turmoil in the bond market may put a spotlight on some of these big questions. Long-term yields remain elevated, partly because investors have priced out fewer interest rate cuts by the Federal Reserve, with strong “hard data” suggesting the economy remains resilient despite uncertainty introduced by President Donald Trump’s tariffs.

Investors might also be demanding a premium for holding U.S. debt because of growing fiscal concerns. Despite Elon Musk’s objections, Republicans are working to pass a “Big, Beautiful” spending bill, which the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office has estimated will increase deficits by $2.4 trillion over the next decade.

If borrowing costs remain high, companies might find it more difficult to finance themselves with long-term credit. So far this year, Sheridan said, firms are issuing fewer 30-year bonds and more intermediate-duration and floating-rate securities.

“So that crowding out effect might be starting to play out with where on the U.S. yield curve corporations want to borrow at,” he said.

More expensive lending, of course, may lead to more companies going under. Since 2022, when the Fed dramatically hiked rates to fight inflation, an annual study by Deutsche Bank has argued the global economy is slowly leaving an “ultra-low default world.”

“While we haven’t yet seen a cyclical spike in defaults—largely due to the avoidance of a U.S. recession—there are clear signs that higher-for-longer funding costs, especially in the U.S., are taking a toll,” Jim Reid, the bank’s global head of macro and thematic research, wrote in a note with colleagues Monday.

The pressure could keep building if Uncle Sam can’t stem its borrowing.

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com

![The Most Searched Things on Google [2025]](https://static.semrush.com/blog/uploads/media/f9/fa/f9fa0de3ace8fc5a4de79a35768e1c81/most-searched-keywords-google-sm.png)

![What Is a Landing Page? [+ Case Study & Tips]](https://static.semrush.com/blog/uploads/media/db/78/db785127bf273b61d1f4e52c95e42a49/what-is-a-landing-page-sm.png)