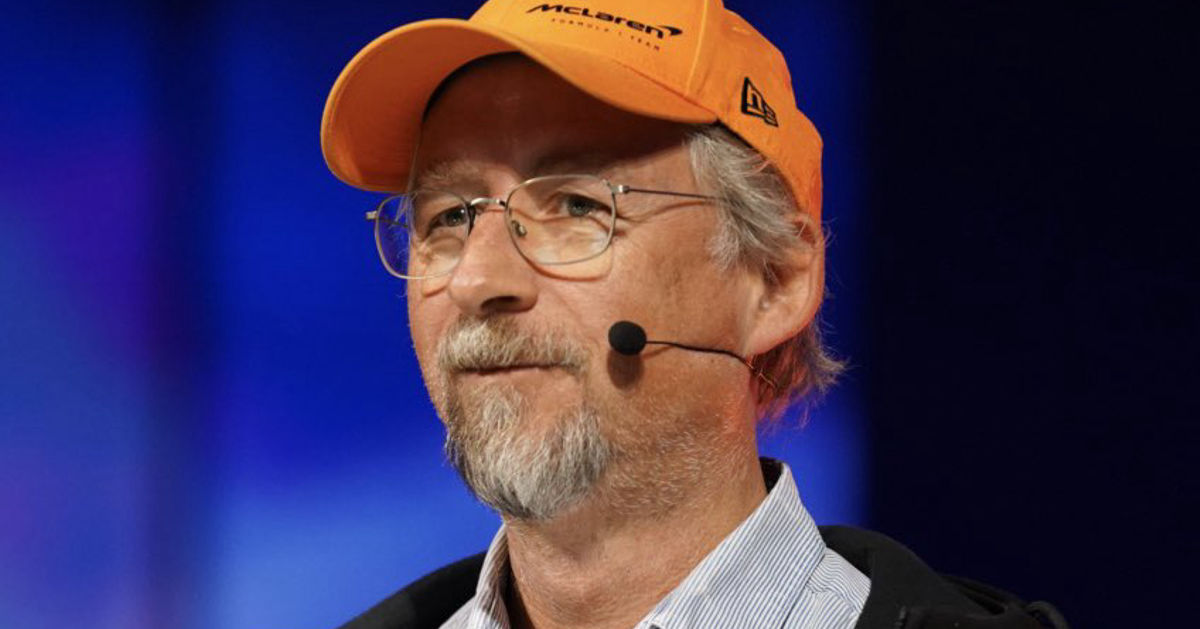

The CEO giving Keurig Dr Pepper a massive energy jolt

Tim Cofer has helped power Dr Pepper past Pepsi and is building the industry’s most aggressive, creative player.

It’s a cloudy afternoon in late March in Burlington, Mass., the Boston suburb that’s the site of co-headquarters for Keurig Dr Pepper. CEO Tim Cofer—who’s just dropped off his suitcase after arriving from KDP’s second home base in Frisco, Texas, near Dallas—is guiding Fortune through the glass-framed modern office building which contains a warren of showrooms. One displays all 16 flavors of Dr Pepper, another shows a panoply of new energy drinks; walking down the hall we visit a gallery arraying dozens of Keurig models, from the K-Mini for dorm rooms to a business-size brewer at over $1,000.

Between extolling the products in each room, the super-salesman describes the promise of this world of liquids, where he’s never worked before, and his mission for KDP. Cofer is instilling the élan of a scrappy underdog in this old-line corporation of 29,000 employees. “We’re hungry, we like to disrupt; this is a challenger culture where we play offense, not defense,” he explains, while standing before a neon-rainbow rack of cans. “There’s a real sweet spot where a company’s large enough to bring the scale in investment and distribution to win in a big way, but keeps the mindset of being nimble, aggressive, and continually dissatisfied with the status quo,” he says.

It’s what motivated Cofer to woo the 38-year-old entrepreneur who founded the popular energy drink Ghost, and in October strike a $1.65 billion deal to acquire the brand. The caffeine-like high of the Ghost tie-up exemplifies the jolt Cofer’s delivering to make KDP an increasingly formidable challenger to the long-ruling kings of beverage, Coca-Cola and PepsiCo. Since joining KDP first as COO in November of 2023, then as CEO in April of last year, Cofer’s been adding fast-growing, high-margin new offerings, from energy and sports hydration drinks to refreshers to ready-to-quaff iced coffees, while simultaneously supercharging the 140-year old flagship Dr Pepper as a top pick for the Instagram generation. Thanks largely to snazzy marketing that’s enticed the quicksilver Gen Y and Gen Z demographic, classic Dr Pepper has raced from a distant third just a few years back to surpass regular Pepsi as the second-bestselling soft drink in North America behind Coke.

In fact, KDP itself—like its signature non-cola—is a one-of-a-kind concoction, the product of a highly experimental blending of businesses. It’s the sole big marketer to combine huge franchises in both hot and cold beverages. That union happened in mid-2018 via the $18.7 billion merger of Dr Pepper Snapple and coffee maker Keurig Green Mountain, making KDP by far the most diversified enterprise in nonalcoholic or “refreshment” beverages with over 125 brands where it’s an owner, investor, or distributor.

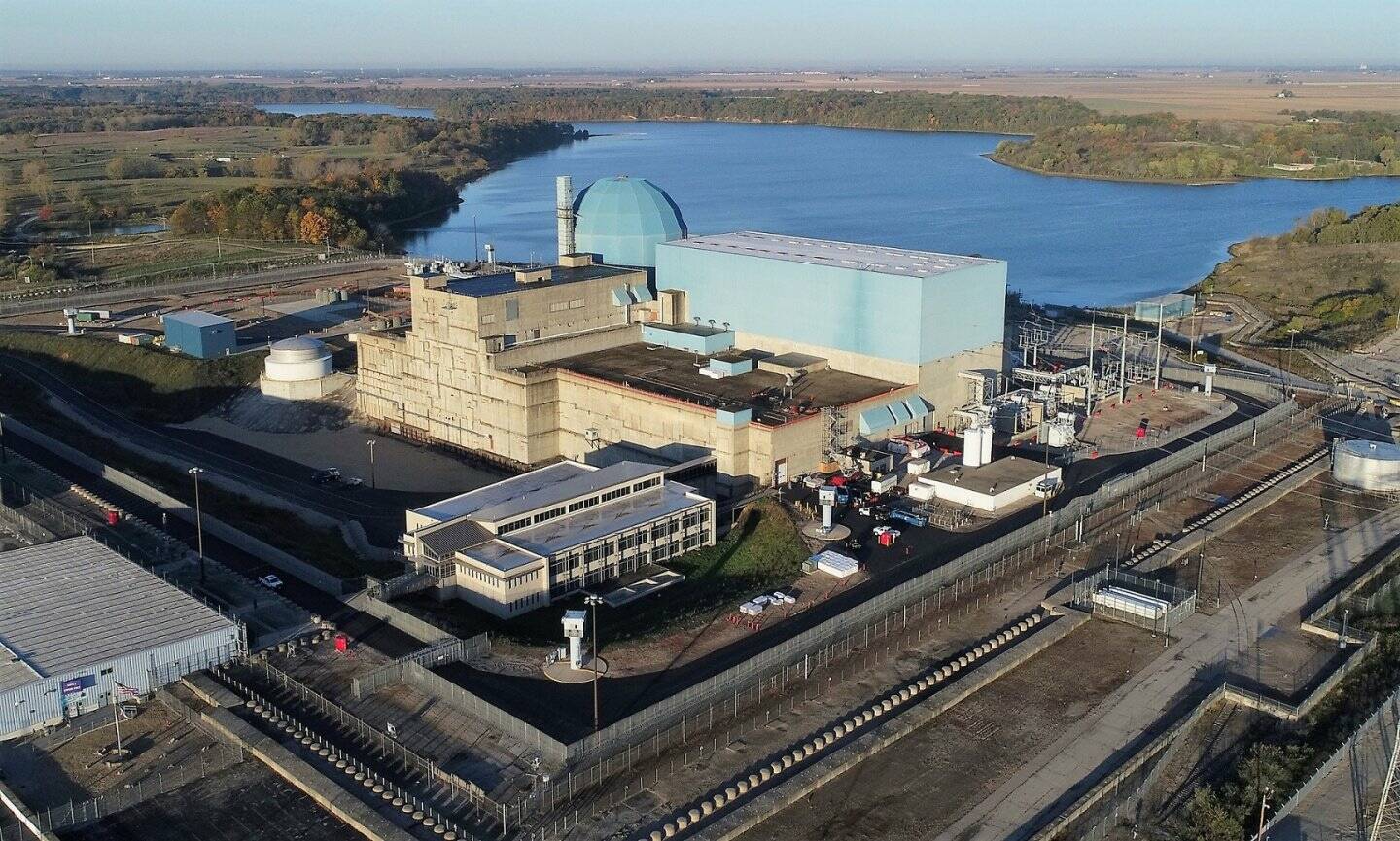

The mating proved a giant success during the pandemic. As the crisis began, then-CEO Bob Gamgort, now KDP’s chairman, brilliantly exploited data flowing from home coffee makers wired to data centers, deploying AI to foresee a spike in demand for coffee and bedrock soft drink brands in the sudden switch to the stay-at-home economy. Gamgort ramped up production of Dr Pepper, Canada Dry, and K-Cups, and secured big shipments of cans from Mexico well before rivals saw the wave building. But since 2022, KDP’s coffee sales have flattened, pressured by a sharp rise in the cost of the raw beans that raised the price of K-Cup pods and pushed folks toward instant brands and making their own. “Now, their crown jewel is beverage, and their problem child is coffee,” notes Connor Rattigan, an analyst at global data provider Consumer Edge.

To lift KDP to Coke-and Pepsi-level profitability, Cofer needs to perform the tough, dual task of making high-margin hits on the supercompetitive soft drink side, while reheating coffee. He’s got big plans for both.

Though little-known for such an important CEO, Cofer spent a long pre-KDP career hopping the globe while recharging and merging many of the most celebrated brands in consumer packaged goods. The C-suite prized Cofer’s knack for engineering quick turnarounds, and cycled him through jobs relatively quickly. He would typically put sales on the fast track, then get the call to move on.

Cofer grew up in White Bear Lake, Minn., on the outskirts of Minneapolis/St. Paul, that’s renowned as a summer resort for angling largemouth bass, and whose namesake Mark Twain described as “lovely sheet of water.” His father started as a line foreman at a 3M ceramics plant, and rose to become a marketing SVP for overhead projectors. The romance of big business captured Tim around age 7, when he’d join his dad on Saturdays for a drive to 3M’s headquarters in St. Paul. “It instilled upon me the importance of work ethic, because my father would be the only one there. I loved walking around staring at the big desks and big offices. I became fascinated by the prototypes for the newest 3M Thermo-Fax copying machines, and would copy their design in pencil,” he recalls. On the trip home, he’d quiz his father about 3M’s organizational structure and workings of its chain of command.

As a student at St. Olaf College near home, Cofer got his first job as the “arms and legs” of a local research agency. He’d visit grocery stores, clipboard in hand, count the “facings” of Honey Nut Cheerios, Lucky Charms, and other General Mills cereals on the shelves, and record the posted prices, at $2.85 an hour. “I soon figured out that I didn’t want to be recording the data, I wanted to be on the other side, using the data to build a brand,” he recalls. In 1992, he finished his MBA as valedictorian from the University of Minnesota’s Carlson School of Management, majoring in marketing, and took a job in Minneapolis at Kraft Foods’ cold-cuts purveyor Oscar Mayer. “I was assistant brand manager for deli meats, maybe not the sexiest of jobs,” he avows. “But I was brand passionate, and it was great foundational learning.”

In 2003, Cofer got his first break when Kraft handed him his introductory general manager role, and control of his own P&L, as chief of the European chocolate franchise that marketed such feted brands as Milka and Toblerone. Cofer relocated to London and set about instituting a dramatic restructuring mandated by headquarters: shifting authority from country managers who previously exercised full control of their businesses to the “regional” level led by Cofer, who took the new position as European VP of chocolate. “This disempowered the country chiefs,” says Ingeborg Gasser-Kriss, Cofer’s innovation chief for Europe. “A newly formed region category team was not something the country heads wanted.” To win Gasser-Kriss’s confidence, Cofer took her on a long walk, for a heart-to-heart talk, on Vienna’s famed Ringstrasse encircling the city’s historical center, rich in baroque architecture.

That was followed by a tour visiting all two dozen country leaders, says Gasser-Kriss. “Tim presented business plans to all of the country teams, and we had dinner with them. He told them, ‘Look, I want us all to agree that if something doesn’t touch the region as a whole, you’ll have all the freedom you need. But if a decision has to be made at the region category, it goes with the region.”

In 2010, Kraft CEO Irene Rosenfeld, Cofer’s mentor, engineered the purchase of British chocolate-maker Cadbury for $19.6 billion in one of the largest food industry transactions ever. She immediately sent Cofer—whom she’d recalled from London in 2007 to first head Oscar Mayer then the Kraft pizza business—to Zurich, to oversee the integration of Kraft and Cadbury chocolate franchises worldwide. The Cadbury deal started as a hostile takeover. “Cadbury was an icon of Britishness from the 1800s,” says Cofer. “They fought the takeover in the business community and the court of public opinion.” Adds Gasser-Kriss, “Cadbury’s proud team called us ‘the American plastic cheese company,’ that’s how much they liked us at the start.”

Rosenfeld had promised big synergies between the two companies to justify the deal’s high price. “Tim had to navigate through rough waters, a lot of people were nervous,” says Rosenfeld. “He had to tell people on both sides they didn’t have jobs in the organization.” Once again, it was Cofer’s expertise in tough-minded diplomacy that won the day. Essential to his success was an unlikely partnership he forged with the figure heading chocolate at Cadbury, Bharat Puri. “Two more different people you couldn’t imagine,” recalls Gasser-Kriss. “Bharat was the life of the party, had a great sense of humor, and loved jokes. Tim was a brain person. On the continuum from sincerity to fun he was much on the sincerity side. One time he showed up at an all-day meeting unshaven, without a jacket and tie, and everybody applauded. Bharat told him, ‘You need to relax!’” Gasser-Kriss greatly admired how Cofer put his deep analytical abilities to work when questioning herself and other lieutenants on their project proposals that needed his approval, sans intimidation. “He would always put his finger on the weak spot,” and that made us better, she remembers. “He was like a precision drone in spotting things that could go wrong.”

Puri recalls that despite their odd-couple chasm in personality, he and Cofer joined hands on the right strategy for merging the best of both Kraft and Cadbury to create the powerhouse in chocolate that’s thriving to this day under Mondelez. Puri, who’s now managing director of Indian consumer and specialty chemicals outfit Pidilite, told Fortune that, at the start of their partnership, Cofer “was too much head and not enough heart. He would tend to be formal and shy.” Gasser-Kriss credits the gregarious Puri with helping Cofer develop a bigger public persona. “They learned new sets of behaviors from each other,” she says. “It wasn’t that Tim was introverted, but he developed an engaging, compelling manner in the town hall mode, and may owe that to Bharat’s example.” For Gasser-Kriss, Cofer showed all and sundry his affection for his brands by naming his beloved Maltese Shih Tzu Toblerone.

A stint in Asia troubleshooting Mondelez’s business (and overseeing the wildly successful launch of Oreo Thins) and a return to the U.S. in 2017 as head of North America under Rosenfeld, then CEO at Mondelez, had Cofer set up as the leading internal candidate to succeed her. Instead, the board awarded the prize to Belgian executive Dirk Van de Put, who’d headed McCain Foods of Canada, the world’s largest producer of frozen french fries and potato specialties. “While I was disappointed, it turned out to be a learning experience working with Dirk,” he says. Inside Mondelez, Cofer created a venture capital group called SnackFutures that proved a forerunner to the stance he’s taking at KDP. The new group backed quirky entrepreneurs to commercialize such innovations as vegan chocolates and plant-based cookies, and made Mondelez a preferred partner for young, hot brands on the rise, presaging Cofer’s purchase of Ghost. To measure what tastes would sell, Cofer insisted on junking the old system that relied on questionnaires and focus groups. Instead, he deployed pop-up stands at schools and farmers’ markets to conduct on-the-spot taste tests for moms dropping off their kids and health-conscious shoppers cruising the fruit and veggie booths.

Most of all, Cofer claims that he benefited richly by watching the divergent styles of Rosenfeld and Van de Put. “From them, I learned the importance of situational leadership,” he relates. “With Dirk, it was the high-level attention to detail. Irene was a master of playing the strategic chessboard, who engineered the Cadbury acquisition, which paved the way for the split from Kraft. I was able to study both styles, and choose times when it’s better to bring a high level of intensity, or to step back and examine the big strategic picture.”

Away from the office, Cofer’s a big tennis and skiing fan. In both sports, it’s been both a family and a worldwide affair. Tim’s two sons, now in their twenties, were captains of their high school tennis teams, and his wife, Jodi, is also an avid player. Cofer’s approach on the court will probably surprise no one. “I play aggressive,” he says. “I play offense, not defense. I like to rush the net,” not recklessly, he avows, but behind deep, strong approach shots. Sitting on the baseline, hitting everything back, is the antithesis of Tim’s game plan for walking off the winner. The family has visited each of the four Grand Slam tournaments in New York, Melbourne, Paris, and London. They have also globe-trotted on skis, taking to the slopes in places as far-flung as Sweden, Japan, and the Czech Republic. In music, Cofer loves classic rock—rap not so much—and his hero is fellow Minnesotan Bob Dylan, whose vinyl discs entranced him as a teen in the ’70s, and whom he’ll fly halfway across the U.S. to catch in concert.

Cofer plays the showman big-time on his video series, Taste Test With Tim, posted on the KDP website. On the episodes running around eight minutes each, he and a guest—either an insider, usually a marketing or an R&D exec, or a KDP beverage partner—sample a new offering. On the shows, Cofer rhapsodizes like a coffee and soft drink sommelier, praising “the toasted coconut notes and creamy notes” of Dr Pepper Creamy Coconut, or the “clean, smooth finish” and “caramel notes” found in a blend of Green Mountain Coffee. Cofer finished one entry by joyously recapping the KDP advertising mantra, “Brew the Love,” exhorting, “We’re brewin’ the love, baby!”

In 1885—one year before the birth of Coca-Cola—a pharmacy operator in Waco, Texas, famously mixed 23 syrups from his adjoining soda fountain in an experiment to re-create the drugstore’s aroma. The tangy blend was Dr Pepper. For many decades, the brand was chiefly a regional favorite in the Southwest. But in 1963, a pivotal legal decision declaring that Dr Pepper isn’t a cola helped take it nationwide. That landmark ruling enabled Dr Pepper to win deals where the network of Coke “Red” and Pepsi “Blue” regional bottlers produced and distributed the brand in sundry markets. Over the years, Dr Pepper established its own “Maroon” system of bottlers and distributors that now cover 80% of the U.S. But Dr Pepper is still blended and shipped by Coke and Pepsi franchises in many parts of the nation. A major advantage from KDP’s continuing cooperation with the two behemoths: Dr Pepper is served in restaurants and fast-food outlets where either Coke or Pepsi are the exclusive offerings. McDonald’s is Coke-only for cola, and Taco Bell is Pepsi only; diners can push the dark red Dr Pepper button at both.

KDP’s nameplate prospers greatly from its role as the leading sponsor of college football. This will be the seventh season it’s been airing ads conjuring a fantasy suburb dubbed “Fansville” whose twin obsessions are the college gridiron and Dr Pepper. Babies emerge from the womb wearing football jerseys and sports caps. Parents bawl out their kids for hiding soccer magazines under their mattresses. Retired football star turned actor Brian Bosworth plays a sheriff chugging Dr Pepper from a quart bottle. Cofer’s so all in on “Fansville” that in December he appeared on one of his Taste Test With Tim episodes shown on YouTube at the SEC championships festooned in a Dr Pepper–labeled football jersey, declaring, “What’s more classic than home-gating and tailgating!”

The trend toward ever zanier mixtures entered a new dimension with an explosion in “dirty soda.” Such beverages gained major traction in the Mormon community, where folks who are barred by their religion from drinking alcohol or hot drinks except herbal tea took to social media announcing that they were having great fun slurping these custom bubblies at drive-in chains Swig and Sonic. In the Hulu reality series The Secret Lives of Mormon Wives, which aired last year, the players lauded dirty soda forays as “my Mormon crack” and “kind of our vice.” A big hit at Swig: “Naughty & Nice,” a swirling mix of Dr Pepper, English toffee syrup, and half-and-half. By 2023, videos of youngsters touting their outlandish dirty soda recipes abounded on TikTok and Instagram. And a top choice as a canvas for this explosion in wild culinary self-expression was Dr Pepper.

First to pounce was KDP. “We realized we were in a zeitgeist moment that offered a rare opportunity to capitalize on a new cultural idea,” says Cofer. The first step came in early 2024 when marketing people at KDP huddled with the folks at Nestlé promoting its nondairy creamer Coffee Mate. Together, they crafted the first mainstream product merging the worlds of coffee creamer and soda, a pairing that was all the rage across social media. Their brainchild was Dirty Soda Coconut Lime Flavor Liquid Creamer, featuring the Dr Pepper logo on the bottle headlined by “Mix with.” “I approved the idea right away,” says Cofer.

In May 2024, KDP introduced the first mass-market dirty soft drink in a can, Dr Pepper Creamy Coconut, which proved to be KDP’s most successful limited-time offering ever. On Feb. 5, KDP followed up by launching another new flavor, this one a perennial named Dr Pepper Blackberry, which, according to analyst Rattigan, is contributing to Dr Pepper’s recent gains on Pepsi and Coke.

But despite the surge, KDP’s profitability lags well behind that of Coke and Pepsi. Accounting expert Jack Ciesielski uses a yardstick called Cash Operating Return on Assets to assess how well companies are deploying all the capital awarded them by shareholders, excluding the effects of taxes and leverage. Last year, Coke and Pepsi registered COROA of 11.5% and 13.1%, respectively. For KDP, the figure was a relatively undistinguished 5.3%.

Still, that shortfall is an opportunity. Cofer points out that total refreshment drink volume nationwide grows around 1% annually, tracking population. The key to putting the fizz in earnings: achieving a richer mix—selling a higher portion of offerings that generate extra dollars per can and bottle. Hence, he’s counting on the big move into the premium territory of energy, sports hydration, ready-to-drink coffee, and refreshers to lift margins, while deploying gridiron marketing and catchy new flavors in KDP’s classic brands to grab share from rivals.

And finally, he’s betting that the launch of K-Rounds will invigorate the lagging coffee business. Unlike the K-Cups that encase the pre-brewed coffee in plastic capsules, K-Rounds are super-densely-packed mounds of ground beans that don’t have packaging; they come in a plant-based coating. Folks will pop the K-Rounds into a new Keurig coffee maker called the Alta. “Remember, Keurigs today are in 45 million homes. We’re the preeminent system, but we’re willing to reprogram ourselves to provide this totally new product,” Cofer intones. “What’s really exciting is that we’re willing to disrupt ourselves.” For decades, Tim Cofer worked for established giants of consumer packaged goods. But as a leader he’s proving himself to be the un-cola of CEOs—and the giants had better take note.

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com

.png)