Humans have irreversibly changed the planet. These photos prove it

On the second and third floors of New York City’s International Center of Photography (ICP), a collection of over 40 years worth of Edward Burtnysky’s vision of industrial, human impact on the planet will be displayed throughout the summer. It’s Burtnysky’s first solo, NYC institutional exhibition show in over 20 years, and is more or less—an ode to his life’s work. [Photo: courtesy International Center of Photography] From some of his earliest work in the 80s as a student on the upper level, to his newer, larger scaled work on the lower, each piece represents the development of human industry through a ‘concerned photography’ lens. [Photo: courtesy International Center of Photography] “All the work kind of pokes around into those zones of globalism and as well as the need for materials, and looking at our population growth,” Burtynysky says. “I was born in 1955 when the world population was under 3 billion people and now we’re over 8 billion. I kind of knew then that we were talking about a human population explosion.” Mines #13, Inco – Abandoned Mine Shaft, Crean Hill Mine, Sudbury, Ontario, Canada, 1984 [Photo: © Edward Burtynsky, courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York] While studying photography in 1981, Burtynsky was working in “big industry” to put himself through school. There, he said he decided to focus on big industries like oil and cobalt mining, and define them through photography. Regardless of place or subject, he says he wanted to focus on one continuous idea— our impact on the world. Breezewood, Pennsylvania, USA, 2008 [Photo: © Edward Burtynsky, courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York] The works range in location and anthropogenic effect. From large, aerial views of chain restaurants and gas companies on the outskirts of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to up-close portraits of recycling workers in China, Burtynsky’s work is meant to feel human and appear visually cinematic. [Photo: courtesy International Center of Photography] According to David Campany, ICP’s creative director and curator of the show, these photos are not the kind meant to be viewed on a smartphone. “I think when you go to the cinema, you’re part of a slightly more collective consciousness, and I think it’s the same when people stand and look at big images,” Campany says. [Photo: courtesy International Center of Photography] The larger scale allows the viewer to get lost in the details within the bigger picture, like being able to look at dusty orange landscapes with sleek lines—but backing up and realizing it’s a commercial road in the middle of the desert. The show brings together around 70 images of Burtynsky’s work, and create a “survey of the last 45 years” of environmental impact. In turn, it makes people look closely at the negative human effect and how each image is interconnected to the larger idea. “You might look at that picture of a mine in the Democratic Republic of Congo in Central Africa and think that’s got nothing to do with me, but 70% of the world’s cobalt currently comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo,” Campany says. “And when you put your hand in your pocket [and feel for your smartphone], you’ve suddenly got a very intimate connection with that image on the wall.” Although there’s no specific method or direction to view or engage with the work, each piece is generally meant to hold “equal value” when it comes to lighting and subject matter importance. Burtynsky refers to this as the “democratic distribution of light and space.” For him, it allows the viewer to “fall into the surface” of the image itself. [Photo: courtesy International Center of Photography] “In 1981, which was my student work, I was looking at our relationship with nature containing nature, controlling nature, greenhouses,and large industrial farms,” Burtynsky says. “Even back then, I realized farming was our biggest impact in the planet, and it’s kind of makes sense to have a farming as a central image for the exhibition.” Despite the works spanning decades of his travels and anthropogenic view, they are all embedded with what he says is a sense of aesthetic, wonder, and impact. Shipbreaking #49, Chittagong, Bangladesh, 2001 [Photo: © Edward Burtynsky, courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York] “Shipbreaking work was some of the most incredible locations I’ve ever photographed and experienced,” Burtynsky says. “It still stands as one of the most crazy experiences of my life. The pictures that came out of that were sort of wild, and [the one you see when] you come out of the elevator where you see all the men—it’s like being greeted by the other world that deals with our shit.” In addition to Burtynsky’s show, ICP is also showing Panjereh, meaning “window” in Farsi, from Iranian-American artist Sheida Soleimani. The exhibition emphasizes her Ghostwriter series, where she “explores her parents’ experiences of political exile and migration”

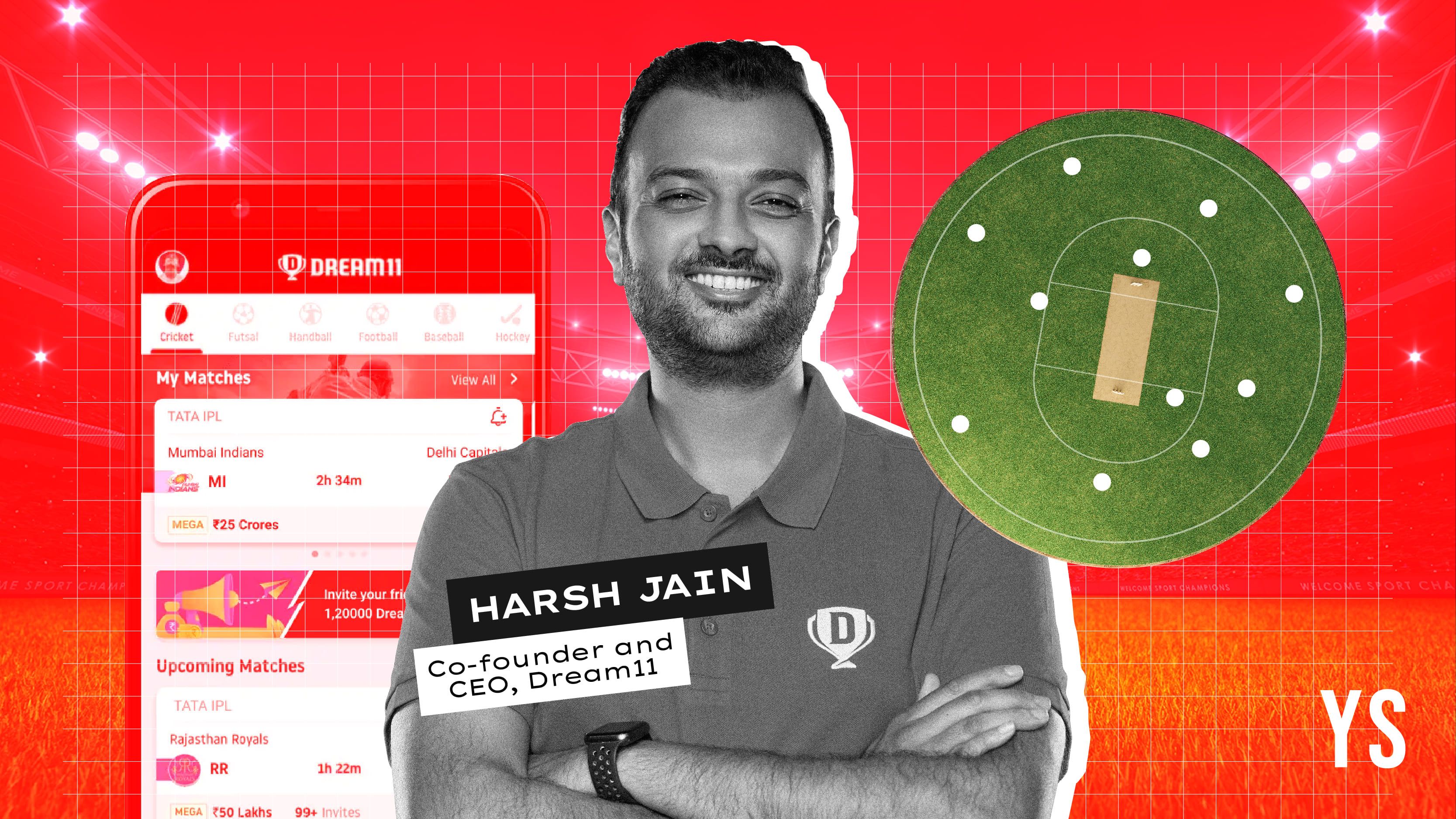

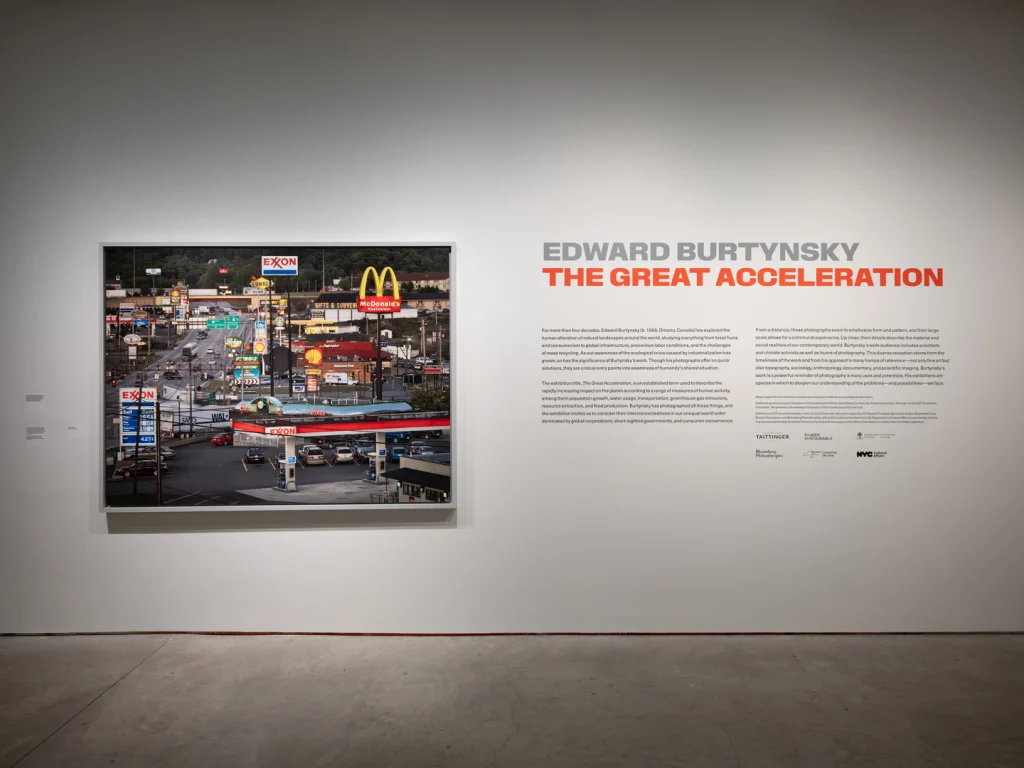

On the second and third floors of New York City’s International Center of Photography (ICP), a collection of over 40 years worth of Edward Burtnysky’s vision of industrial, human impact on the planet will be displayed throughout the summer.

It’s Burtnysky’s first solo, NYC institutional exhibition show in over 20 years, and is more or less—an ode to his life’s work.

From some of his earliest work in the 80s as a student on the upper level, to his newer, larger scaled work on the lower, each piece represents the development of human industry through a ‘concerned photography’ lens.

“All the work kind of pokes around into those zones of globalism and as well as the need for materials, and looking at our population growth,” Burtynysky says. “I was born in 1955 when the world population was under 3 billion people and now we’re over 8 billion. I kind of knew then that we were talking about a human population explosion.”

While studying photography in 1981, Burtynsky was working in “big industry” to put himself through school. There, he said he decided to focus on big industries like oil and cobalt mining, and define them through photography. Regardless of place or subject, he says he wanted to focus on one continuous idea— our impact on the world.

The works range in location and anthropogenic effect. From large, aerial views of chain restaurants and gas companies on the outskirts of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to up-close portraits of recycling workers in China, Burtynsky’s work is meant to feel human and appear visually cinematic.

According to David Campany, ICP’s creative director and curator of the show, these photos are not the kind meant to be viewed on a smartphone.

“I think when you go to the cinema, you’re part of a slightly more collective consciousness, and I think it’s the same when people stand and look at big images,” Campany says.

The larger scale allows the viewer to get lost in the details within the bigger picture, like being able to look at dusty orange landscapes with sleek lines—but backing up and realizing it’s a commercial road in the middle of the desert. The show brings together around 70 images of Burtynsky’s work, and create a “survey of the last 45 years” of environmental impact. In turn, it makes people look closely at the negative human effect and how each image is interconnected to the larger idea.

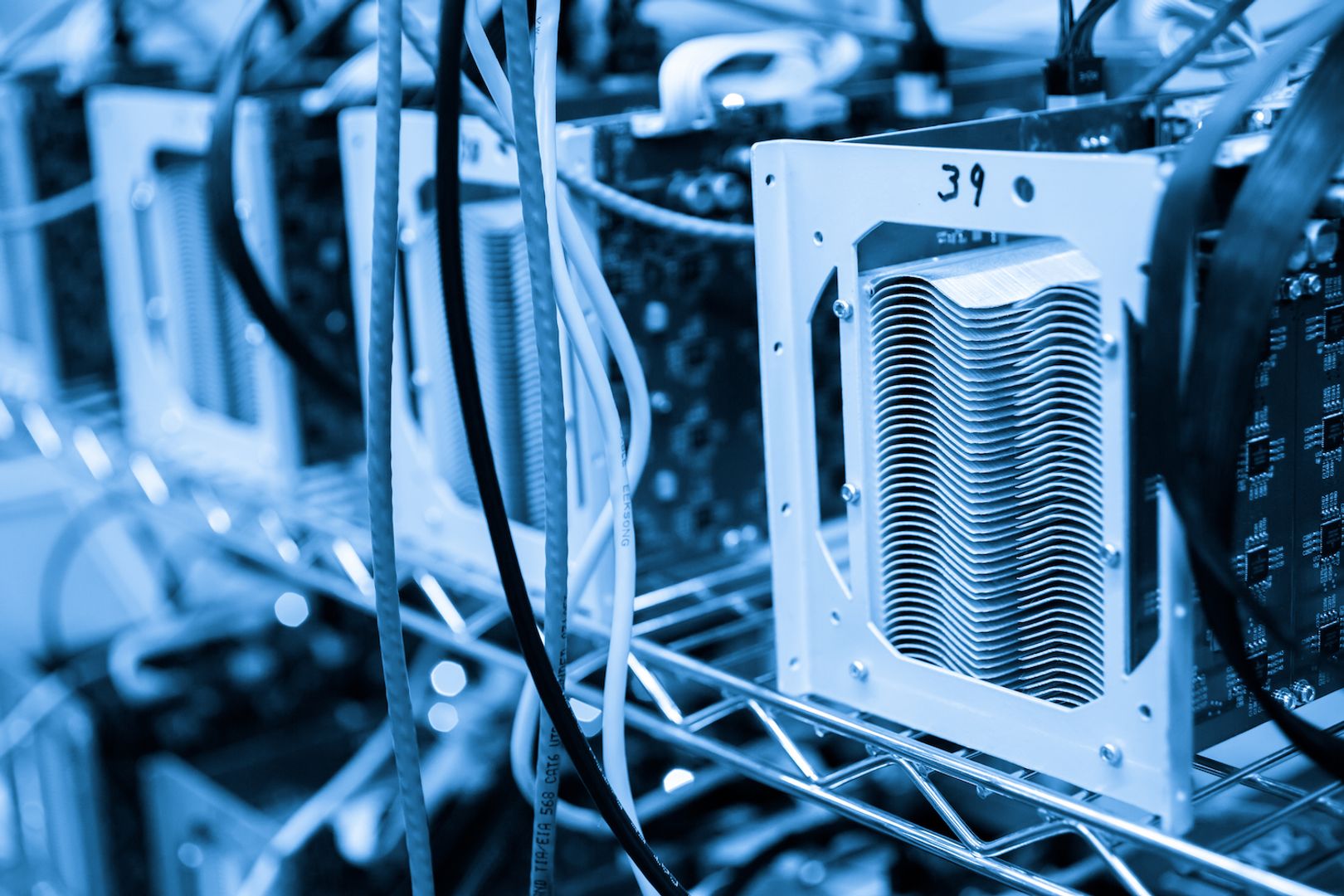

“You might look at that picture of a mine in the Democratic Republic of Congo in Central Africa and think that’s got nothing to do with me, but 70% of the world’s cobalt currently comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo,” Campany says. “And when you put your hand in your pocket [and feel for your smartphone], you’ve suddenly got a very intimate connection with that image on the wall.”

Although there’s no specific method or direction to view or engage with the work, each piece is generally meant to hold “equal value” when it comes to lighting and subject matter importance.

Burtynsky refers to this as the “democratic distribution of light and space.” For him, it allows the viewer to “fall into the surface” of the image itself.

“In 1981, which was my student work, I was looking at our relationship with nature containing nature, controlling nature, greenhouses,and large industrial farms,” Burtynsky says. “Even back then, I realized farming was our biggest impact in the planet, and it’s kind of makes sense to have a farming as a central image for the exhibition.”

Despite the works spanning decades of his travels and anthropogenic view, they are all embedded with what he says is a sense of aesthetic, wonder, and impact.

“Shipbreaking work was some of the most incredible locations I’ve ever photographed and experienced,” Burtynsky says. “It still stands as one of the most crazy experiences of my life. The pictures that came out of that were sort of wild, and [the one you see when] you come out of the elevator where you see all the men—it’s like being greeted by the other world that deals with our shit.”

In addition to Burtynsky’s show, ICP is also showing Panjereh, meaning “window” in Farsi, from Iranian-American artist Sheida Soleimani. The exhibition emphasizes her Ghostwriter series, where she “explores her parents’ experiences of political exile and migration” through layered, magically surreal pieces. Both exhibits can be viewed simultaneously at the ICP. from June 19 until September 28.

![How Social Platforms Measure Video Views [Infographic]](https://imgproxy.divecdn.com/AncxHXS242CT-kDlEkGZi7uQ2k70-ebTAh7Lm14QKb8/g:ce/rs:fit:770:435/Z3M6Ly9kaXZlc2l0ZS1zdG9yYWdlL2RpdmVpbWFnZS9ob3dfcGxhdGZvcm1zX21lYXN1cmVfdmlld3MucG5n.webp)

![How Google’s AI Mode Compares to Traditional Search and Other LLMs [AI Mode Study]](https://static.semrush.com/blog/uploads/media/86/bc/86bc4d96d5a34c3f6b460a21004c39e2/f673b8608d38f1e4be0316c4621f2df0/how-google-s-ai-mode-compares-to-traditional-search-and-other-llms-ai-mode-study-sm.png)