A Professor and Pioneer in Artificial Intelligence: Vijay Chandru

Professor Vijay Chandru shares his storied career in academia and entrepreneurship, how to balance both sides of the AI coin, and how

Professor Chandru, born and raised in Chennai, attended Don Bosco Matriculation when he discovered a passion for mathematics. In what he terms as an “extraordinary pivot”, he left the familiarity of South India to pursue an Electrical Engineering degree at BITS Pilani in 1970. At the time, BITS Pilani and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) had a strong connection - one that would forge a new path in Professor Chandru’s life.

“We had visiting faculty from MIT and other parts of the world at BITS Pilani. In my final year, the director, who was very well connected, invited British theorist Anthony Stafford Beer who was one of the pioneers of cybernetics in the UK. It was remarkable. He gave us a few lectures on cybernetics, which was in some sense, one of the foundations of AI”, says Professor Chandru.

As a result, he packed his bags for the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), with cybernetics and systems engineering in his sights. Cybernetics - the study of control and communication in complex systems, such as living organisms, machines or social systems - left a deep impression on Professor Chandru. He completed his masters degree in systems engineering at UCLA, before completing his PhD at MIT - the birthplace of cybernetics.

“I didn't study AI formally. At the time we used to think of it as a branch within decision sciences. It was after I completed my PhD and started teaching at Purdue University, that I realised there was a lot of interest in manufacturing, robotics and automation. I then received a grant from the prestigious Hughes Aircraft Company to apply AI in engineering”, says Professor Chandru.

As he continued to work on flexible manufacturing systems, involving robots, he began to look at formal reasoning systems and computational logic. “For me, it was essentially a way to think about how to engineer and solve problems, and make systems more efficient.” he shared.

Professor Chandru then returned to India to take up a position at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) in the Computer Science and Automation department. Surrounded by extraordinary faculty, he was at the epicenter of machine learning in India. This team was responsible for foundational work in Machine Learning (ML) and neural networks. Professor Chandru recalls that one of his colleagues was instrumental in the development of the kernel method in support vector machines.

“All of this was around the mid 90s, when it occurred to us that the biological sciences were at the stage where they needed machine learning and AI-based methods. That slowly led us to look at problems in bioinformatics and genomics in particular, due to the Human Genome Project. Additionally, IISc was at the stage where the idea of professors starting companies was discussed by Mr. Ratan Tata,” he said.

Bridging the divide: Academia and entrepreneurship

Academics and entrepreneurs, on the surface, are often placed on two ends of the spectrum - based on differing goals, priorities and approaches. Knowledge creation battles it out with value creation, critical analysis with competition, and long-term impact with lightning-fast innovation. However, the two have also built symbiotic relationships, where academia provides the foundational knowledge, which entrepreneurs translate into action. Professor Chandru understands the complex relationship between the two, dubbing it the “Saraswathi-Lakshmi divide”.

He walks the delicate line between the two - drawing the best from each field. “Being an academic is actually the perfect training for being an entrepreneur. You can be someone who works as a professor and also think about building a business”, he says.

As an active research professor, Professor Chandru has maintained labs, received grants, pulled in funding, marketed his work, won awards and managed lab employees — all of which have honed his entrepreneurial skills. The difference between the two, he shares, is simply the speed at which it all happens.

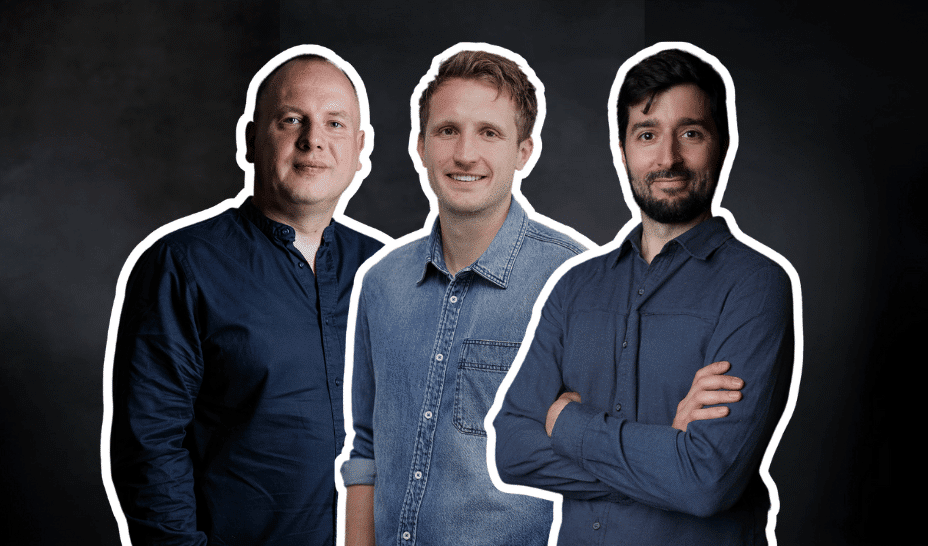

His move into the entrepreneurial arena was spurred by Ratan Tata, Former Chairperson, Tata Group, who was the president of the IISc court. Tata suggested that professors venture into entrepreneurship. So, Professor Chandru, along with his colleagues Ramesh Hariharan, Swami Manohar and V. Vinay stepped forward and volunteered to build businesses - Strand Genomics being one of them.

Setting up Strand: India’s first AI company

In the mid-90s, Professor Chandru and his colleagues at IISc were working on organising computational biology, more as an intellectual pursuit, when they realised that that biology was an important application area for computer science. IISc was well equipped to explore this endeavour, with its Molecular Biophysics Unit (MBU). At the time, the researchers at the unit required the integration of computer science, mathematics and statistics to parse and analyse biological data. As a result, Professor Chandru and his colleagues saw the value of evolving from technical experts who advised biologists to actively drive bioinformatics from a computer science perspective. As a result, Strand Genomics was born.

“The four of us (Chandru, Hariharan, Manohar and Vinay) stepped out and created Strand Lifesciences, which we initially called Strand Genomics. What was interesting, and what very few people know, is that it was India’s first AI company. The whole premise of Strand was that biological sciences were entering the fourth paradigm - data driven science. And so we need a whole new set of tools for that purpose”, he shares.

Strand Genomics (hereafter referred to as Strand) was one of the few biotech companies that was started and powered by computer scientists at the time. Supported by a thriving consulting practice at the university, Strand didn’t require seed capital, instead leapfrogging to series A funding — where they received funds from Ascent Capital, followed by a second investor Westbridge Capital Partner. The next big break in Strand history was its success in Japan.

“Our work in Japan got noticed, because we were taking market share from American companies, so California-based companies like Agilient and Illumina approached us and became partners. We didn’t have to build a sales network. Everything happened through our channel partners, who would connect us with research labs around the world, while we would build the software from Bangalore. We became a thriving bioinformatics shop, building products and improving AI methodologies” he says.

In 2012, the founders of Strand decided to pivot the company from a pure informatics company to working in genomics. At the time, they leveraged a new technology called Next Generation Sequencing (NGS), which allows for the swift and cost effective sequencing of vast amounts of DNA or RNA. This enabled Strand’s scientists to sequence large parts of the genome or even the entire genome, which is roughly 3 billion letters long. They would take 30 copies of the DNA (around 100 billion letters), sequence it by chopping it into small pieces, get shorter sequences and then assemble it, allowing them to understand genes on a deeper level, identify genetic variations and study how organisms evolve.

The entire process was powered by GPUs. The company also used algorithms to great effect to predict the gaps in sequencing, minimise errors and accelerate the assembly of full genome sequences. “To this day, Strand is probably unique in that the entire informatics stack for handling genome sequencing analytics and reporting is all done in-house. It allowed us complete control over informatics”, says Professor Chandru.

Working with the clinical samples of cancer patients and those with genetic disorders, it became a mission of the company to unravel the mysteries of mutations that lead to disease. The work, Professor Chandru shares, is driven by precision. Geneticists often swim in a vast ocean of data, while trying to zero in on the smallest changes. He cites the example of sickle cell anemia, which is caused by the ‘flip’ of a single DNA base pair to illustrate the delicate nature of Strand’s and other geneticists' work.

In 2016, when Professor Chandru was facing retirement in academics, he decided to step back as chairman, bequeathing the role of CEO to Strand’s CTO Ramesh Hariharan. He stayed on as a Board Member and Chair of the Science Advisory Board.

Strand was acquired by Reliance Group in 2021, and is continuing its mission to democratise genomics.

AWS and Strand: a collaboration in compliance

Strand and Amazon Web Services (AWS), have, over the years, created an increasingly intertwined partnership. The life sciences company has leveraged AWS’ cloud computing infrastructure in order to enhance its genomics software and services. The partnership with AWS allows Strand to complete several bioinformatics tasks, such as data processing, analysis and interpretation, as well as streamlining workflows for large-scale genomic analysis.

When discussing the ethical concerns of leveraging AI in life sciences, healthcare and medicine, Professor Chandru acknowledged his gratitude to the tech giant, sharing that it was one of the first cloud systems that was HIPAA compliant.

AI and healthcare - achieving a greater standard of care

AI is going to be very important for healthcare, Professor Chandru stressed. He believes that ASHA (Accredited Social Health Activists) and community workers will be empowered by AI to deliver an increased standard of care to patients. He observed that physicians, too, have also progressed when it comes to using AI, leveraging it for radiology, pathology and imaging.

AI is also having a profound impact on surgeons like Professor Chandru’s daughter who is a pediatric neurologist. He spoke about the use of robotics in surgeries calling it a phenomenal practice. He admits that there will be challenges as AI embeds itself deeper into healthcare practices, but maintains an optimistic outlook of the future.

“There are always challenges as technology progresses. But, I think I'm very excited about the convergence of AI, biology, bioengineering, and new materials… that is the future, which has been called Superconvergence by Metzl”, he says referencing the book Superconvergence where geopolitical commentator, OneShared.World founder and author Jamie Metzl discusses how AI, genome sequencing, gene editing and other groundbreaking technologies are transforming human lives, the planet and our future. The book discusses how these rapidly evolving and interconnected technologies will have a profound impact on health, food supply, global economies and much more.

Continuing in this vein, Professor Chandru shares that at the moment the planet is struggling, burdened by climate change, environmental damage, food security, increasing healthcare challenges and much more. The solution will be in the convergence of technologies like AI.

The Indian AI landscape: On the path to open datasets

When it comes to India’s AI roadmap, Professor Chandru advises that the focus should be data driven, and that experts should concentrate on developing deep learning capabilities and AI methodologies.

“We need to be curating our own data. I believe that this is one of the key reasons that has slowed down India’s AI capabilities. If we want to catch up, we, as a culture, should put together high-quality, curated and annotated data which can then be leveraged for a variety of functions”, says Professor Chandru.

Professor Chandru believes that India continues to be in the early stages of becoming an AI-driven nation. While he believes that the financial services industry has created deep inroads into their data with AI, the healthcare and medical sectors need to invest in creating data assets and then make that available for further ideation and innovation.

When he is not juggling his roles as a teacher, mentor, founder, researcher and advisor, Dr. Chandru is a sports enthusiast, and speaks fondly of enjoying cricket since his school days.

![The Most Searched Things on Google [2025]](https://static.semrush.com/blog/uploads/media/f9/fa/f9fa0de3ace8fc5a4de79a35768e1c81/most-searched-keywords-google-sm.png)

![What Is a Landing Page? [+ Case Study & Tips]](https://static.semrush.com/blog/uploads/media/db/78/db785127bf273b61d1f4e52c95e42a49/what-is-a-landing-page-sm.png)