UX and product designers start with the same salaries. They end up miles apart

UX designers and product designers have very similar jobs. They both arrange digital parts. They both use Figma more than other designers do. And, according to a recent Fast Company analysis of design job listings, they start out with pretty much the same entry-level salary, around $70,000 a year. But as their careers progress, those salaries diverge. Among job postings asking that a candidate have between four and five years of experience, the average salary offered for UX designers was about $123,720, while the salary for product designers was $149,850. By the time these types of designers reach more developed stages of their careers, requiring at least eight years of experience, UX designers are offered an average of about $153,920, while product designers can earn $197,579. That’s about 28% more for product designers. UX design vs. product design To understand what might be driving the discrepancy in salary between UX and product designers over the course of their careers, it is helpful to look at differences in the actual duties that each type of worker performs, and how their careers typically progress. A UX designer is responsible for the feel and flow of a product, e.g. the user experience, while a product designer oversees both visual elements of an app or website and what types of features it should even have to begin with. Alexander Benz, a UX designer, product manager, and CEO of Blikket, a design and development agency for DTC brands, explains that people who start out as UX designers tend to go on become UX managers, involved in the production of a product’s design system, or they become other kinds designers. But as product designers develop in their careers, they begin branching out into other parts of the business, interfacing with stakeholders from across the organization. “When you get into the product,” he says, “then you also have a bigger responsibility to . . . [take] in the ideas from stakeholders and manage more people in the whole process.” For example, while a UX designer might create a flowchart and visual style for a money transfer feature in a banking app, the product designer is closer to the metal, helping determine what components the app’s feature should actually contain—Does it save a list of past transfer recipients? Does it autocomplete input fields?—and so on, while considering the feature’s broader success metrics and technical constraints. “I think that is where the salary difference comes in.” UX designers everywhere Another factor that could be contributing to the salary discrepancy is supply. There are simply more UX designers today than product designers. This may be because UX design boot camps, such as General Assembly and Springboard, proliferated in the 2010s, when interest rates were low, capital was cheap, and a new startup was seemingly being born every minute. These young companies all needed tech-savvy designers on staff to create their wireframes and user journeys, and boot camps minted them. Boot camps are based on the notion that certain jobs require practicing and perfecting a mostly fungible set of best practices that can be deployed to any client. Boot camps are accessible, cheaper than college or graduate school, and have created hundreds of thousands of additional workers in their respective fields. But while there were many boot camp options for budding UX designers, no such counterpart emerged for product designers. There is no oversupply, Benz says. Instead, product designers occupy roles in their companies that are more difficult to delineate. Their jobs require technical and soft skills that take more than a few months to master. There is no crash-course curriculum in product design. More good news for product designers Product designers are enjoying an extra advantage right now. Because their jobs can’t be codified into a standard set of steps and principles, they are largely protected from LLMs. As language models become more sophisticated at performing junior- and, increasingly, senior-level coding tasks, they are threatening all sorts of jobs in tech. It’s the jobs that LLMs don’t understand that are arguably safest. In other words, the very qualities that make UX designers a target for easy boot camps also make them a target for AI. And the job description of a product designer—the fact that the role involves constant communication with individuals inside and outside an organization—means that it is relatively more protected from automation. For UX designers who might be looking for both a salary boost and a shovel to dig an anti-automation moat around their careers, it’s a great time to pivot. This article is part of Fast Company‘s continuing coverage of where the design jobs are, including this year’s comprehensive analysis of 170,000 job listings.

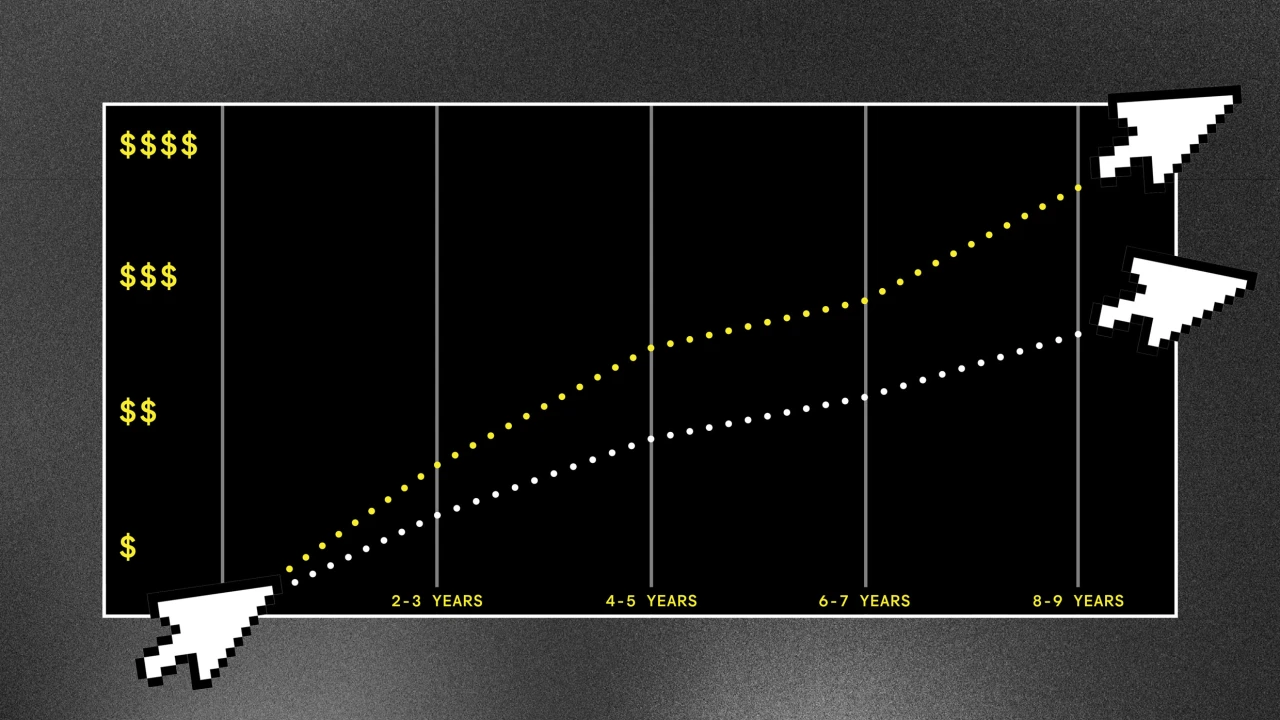

UX designers and product designers have very similar jobs. They both arrange digital parts. They both use Figma more than other designers do. And, according to a recent Fast Company analysis of design job listings, they start out with pretty much the same entry-level salary, around $70,000 a year.

But as their careers progress, those salaries diverge. Among job postings asking that a candidate have between four and five years of experience, the average salary offered for UX designers was about $123,720, while the salary for product designers was $149,850. By the time these types of designers reach more developed stages of their careers, requiring at least eight years of experience, UX designers are offered an average of about $153,920, while product designers can earn $197,579. That’s about 28% more for product designers.

UX design vs. product design

To understand what might be driving the discrepancy in salary between UX and product designers over the course of their careers, it is helpful to look at differences in the actual duties that each type of worker performs, and how their careers typically progress. A UX designer is responsible for the feel and flow of a product, e.g. the user experience, while a product designer oversees both visual elements of an app or website and what types of features it should even have to begin with.

Alexander Benz, a UX designer, product manager, and CEO of Blikket, a design and development agency for DTC brands, explains that people who start out as UX designers tend to go on become UX managers, involved in the production of a product’s design system, or they become other kinds designers. But as product designers develop in their careers, they begin branching out into other parts of the business, interfacing with stakeholders from across the organization.

“When you get into the product,” he says, “then you also have a bigger responsibility to . . . [take] in the ideas from stakeholders and manage more people in the whole process.” For example, while a UX designer might create a flowchart and visual style for a money transfer feature in a banking app, the product designer is closer to the metal, helping determine what components the app’s feature should actually contain—Does it save a list of past transfer recipients? Does it autocomplete input fields?—and so on, while considering the feature’s broader success metrics and technical constraints. “I think that is where the salary difference comes in.”

UX designers everywhere

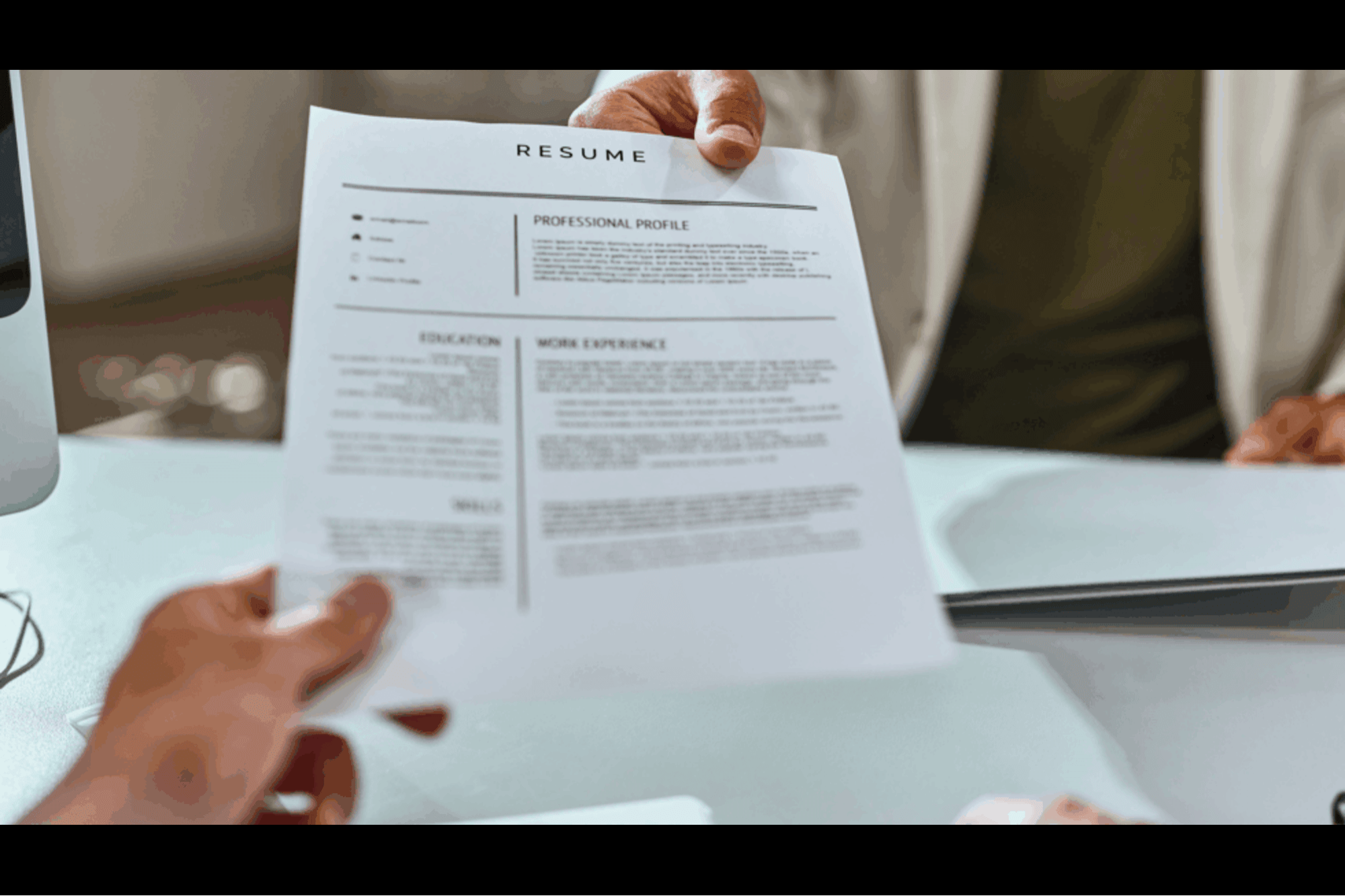

Another factor that could be contributing to the salary discrepancy is supply. There are simply more UX designers today than product designers. This may be because UX design boot camps, such as General Assembly and Springboard, proliferated in the 2010s, when interest rates were low, capital was cheap, and a new startup was seemingly being born every minute. These young companies all needed tech-savvy designers on staff to create their wireframes and user journeys, and boot camps minted them.

Boot camps are based on the notion that certain jobs require practicing and perfecting a mostly fungible set of best practices that can be deployed to any client. Boot camps are accessible, cheaper than college or graduate school, and have created hundreds of thousands of additional workers in their respective fields.

But while there were many boot camp options for budding UX designers, no such counterpart emerged for product designers. There is no oversupply, Benz says. Instead, product designers occupy roles in their companies that are more difficult to delineate. Their jobs require technical and soft skills that take more than a few months to master. There is no crash-course curriculum in product design.

More good news for product designers

Product designers are enjoying an extra advantage right now. Because their jobs can’t be codified into a standard set of steps and principles, they are largely protected from LLMs. As language models become more sophisticated at performing junior- and, increasingly, senior-level coding tasks, they are threatening all sorts of jobs in tech. It’s the jobs that LLMs don’t understand that are arguably safest.

In other words, the very qualities that make UX designers a target for easy boot camps also make them a target for AI. And the job description of a product designer—the fact that the role involves constant communication with individuals inside and outside an organization—means that it is relatively more protected from automation.

For UX designers who might be looking for both a salary boost and a shovel to dig an anti-automation moat around their careers, it’s a great time to pivot.

This article is part of Fast Company‘s continuing coverage of where the design jobs are, including this year’s comprehensive analysis of 170,000 job listings.

![Is ChatGPT Catching Google on Search Activity? [Infographic]](https://imgproxy.divecdn.com/RMnjJQs1A7VQFmqv9plBlcUp_5Xhm4P_hzsniPsfHiU/g:ce/rs:fit:770:435/Z3M6Ly9kaXZlc2l0ZS1zdG9yYWdlL2RpdmVpbWFnZS9kYWlseV9zZWFyY2hlc19pbmZvZ3JhcGhpYzIucG5n.webp)