The New Yorker features Robert Lang and the incineration of his origami

You heard it here first, folks, so the New Yorker was slow on the uptake (and they don’t have the photos and videos that I featured). At any rate, the new issue features the recent story of Robert Lang, master origami artist and reader, whose wildlife photographs have been featured here often (and there are … Continue reading The New Yorker features Robert Lang and the incineration of his origami

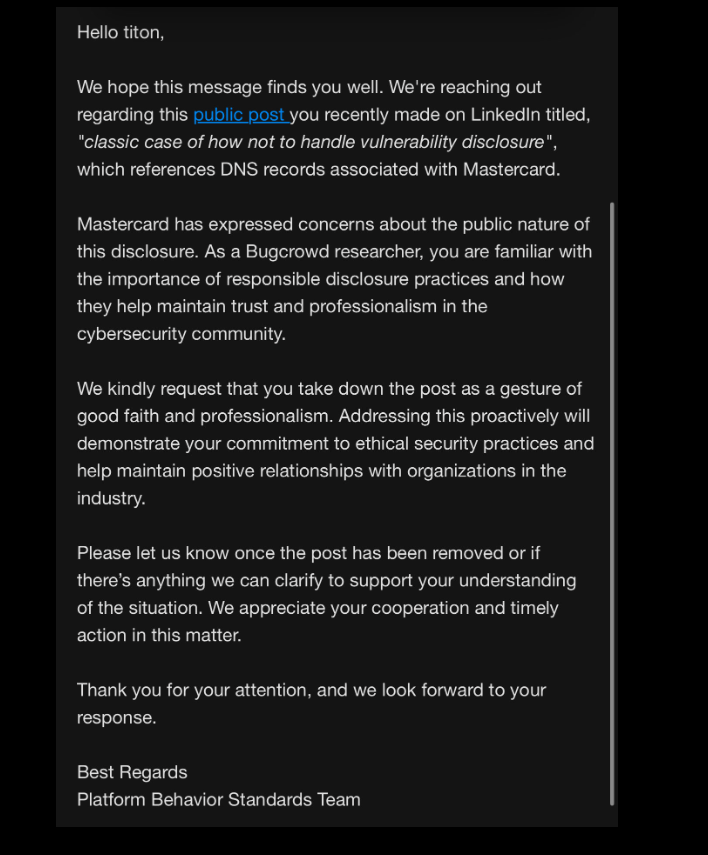

You heard it here first, folks, so the New Yorker was slow on the uptake (and they don’t have the photos and videos that I featured). At any rate, the new issue features the recent story of Robert Lang, master origami artist and reader, whose wildlife photographs have been featured here often (and there are more to come). If you don’t have a subscription, you can click on the NYer headline below and read the piece perhaps once, but otherwise I’ll give some excerpts from the story and add that a judicious inquiry might yield a pdf.

First, though, have a look at Robert’s origami page to see the incredible art he’s made. (I’ll wager he’s one of the ten best origami artists in the world.) As he told me, he lost virtually all of the art he had kept during the fire, which burned up his and his wife’s old home and studio, as well as a new home down the block. They have insurance and will rebuild. In the meantime, I told him that I still had an origami duck he folded for me, and he responded that it was probably one of the few surviving original Langs. It sits atop my computer, and here it is (it is another version of his “Duck Opus 11” on watercolor paper that you can see here).

And the story:

Here are some excerpts:

“The first thing you think of when you see your home engulfed in flames is, My world and future have changed,” Robert J. Lang, one of the world’s foremost origami artists and theorists, said recently. He was sitting in a small hotel room in Arcadia, California. The week prior, the house where he lived with his wife, Diane, had burned down when the Eaton Fire erupted and swept through Altadena, outside Los Angeles, with incredible speed, levelling entire neighborhoods. Robert’s studio, a separate property where he kept decades of his professional origami work—all highly flammable— along with research and personal artifacts, was also reduced to ash.

Diane walked in with their two dogs, Casey and Scout, who hopped onto the mattress and lay down. Diane, with no other place to sit in the room, joined them. “Two people offered their back yards for them to wander around in,” she said. “So, we were just in a back yard.”

The Langs had gone to sleep on a Monday night in their own bed. By Tuesday night, they were sleeping in their cars, with their many pets—the two dogs, two desert tortoises (Sal and Rhody), a Russian tortoise (Ivan), a snake (Sandy), and a tarantula (Nicki)—and the few things they could grab as they fled the inferno. The snake, tortoises, and tarantula were now being taken care of at the San Dimas Canyon Nature Center, rather than staying at the hotel. “Just to make my life simpler,” Diane, who works with the Eaton Canyon Nature Center, said.

In the early hours of Wednesday morning, Robert watched his studio burn from a nearby ridge. Then, at around 9 A.M., he and Diane learned that their home was destroyed. At sixty-three years old, Robert, who was profiled in this magazine in 2007, has been designing origami for most of his life; one of his early designs, in the seventies, was an origami Jimmy Carter. He used to be a physicist, working on things like semiconductor lasers, at places such as NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab, before he decided to devote his time fully to origami. The studio held much of his art, and all of his tools. The laser cutter he used to help make prototypes had melted. “It’s now a pile of metal,” he said. “A 3-D printer is now a pile of ash.” Rare paper, including fig-based paper from a tiny village in Mexico, had burned. He went on, “There were correspondence letters with other origami artists over the years that were a historical record for me and perhaps for others. And then my exhibition collection was there. The pieces I had in MoMA”—a large grizzly bear, a bull moose, and a fiddler crab, all folded between 2003 and 2007—“are gone.” As he evacuated, however, he was able to grab a single piece of art work, perhaps his most famous: a framed, fifteen-inch cuckoo clock folded into dazzling complexity from a single sheet of paper

. . . .Most of the Langs’ days now are spent on details. Dealing with insurance. Filing documents of everything lost. Texting with neighbors. Walking the dogs. Checking the weather for changes in wind. Monitoring evacuation zone updates from the Watch Duty app. And, mainly, finding a more stable place to live.

Robert’s phone rang. Their real-estate agent had a prospective rental apartment they could see that afternoon.

“Ask him about the dogs,” Diane said to Robert. She explained, “We’d founda place we liked—a good vibe. But the owner said he didn’t want dogs.”

Robert hung up. “They take dogs,” he said. “We can see it at 3 P.M.”

“It’ll probably be for two years,” Diane said. “But we’ll rebuild. We still have our land. We even have the floor plans.”

And they will rebuild on the site of their new home and of their original studio. It may take a couple of years, but, as I said in my previous post, the Langs are remarkably resilient and are just getting on with what they need to do.

As for the cuckoo clock he saved: here it is, reproduced with permission. You can see it and read about it here, but he adds:

This is the one I saved. There are four of them in existence (that I folded; lots of other people have followed the folding instructions to make their own versions). One of them was also in a fire that destroyed the owners’ apartment, but almost miraculously, it survived. He had a fourth-floor apartment in a building in which all the interior collapsed in the fire. After the fire, he was poking through the rubble in the basement, lifted a collapsed door that he recognized as his, and found the cuckoo clock, flattened, but unburnt. He sent it to me, and I spent some time restoring it (dampening, wiping off the ash that caked it, and re-folding/re-shaping it). I eventually got it back to its original appearance, though it still had bits of ash in crevices and smelled of smoke, but that just added to its character, and to my knowledge, it survives to this day.]

Here’s the first time I met Robert—at the Kent Presents meeting in Connecticut in August, 2018. (There’s a description here; sadly I’ve removed all photos from this site before January of last year because of copyright claims by stupid and venal firms, but there is a video of some origami that I’ve put below.) This photo shows part of Robert’s presentation, which was accompanied by slides of his artwork). Here Lang (left) talks to biology Nobel laureate Harold Varmus:

Here’s the video showing some of Robert’s origami:

What's Your Reaction?

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)