Lessons from YouTube’s Extreme Makers

In 2006, a high school student from Ontario named James Hobson started posting to a new platform called YouTube. His early videos were meant for ... Read more The post Lessons from YouTube’s Extreme Makers appeared first on Cal Newport.

In 2006, a high school student from Ontario named James Hobson started posting to a new platform called YouTube. His early videos were meant for his friends, and focused on hobbies (like parkour) and silliness (like one clip in which he drinks a cup of raw eggs).

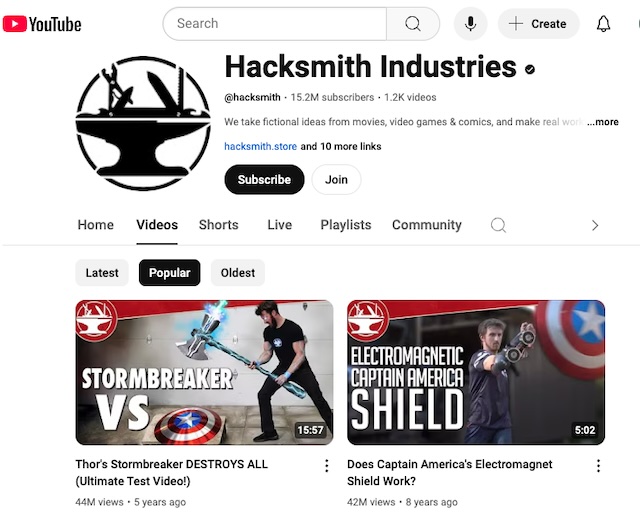

Hobson’s relationship with YouTube evolved in 2013. Now a trained engineer, he put his skills to work in crafting a pair of metal claws based on the Marvel character, Wolverine. The video was a hit. He then built a working version of the exoskeleton used by Matt Damon’s character in the movie Elysium. This was an even bigger hit. This idea of creating real life versions of props from comics and movies proved popular. Hobson quit his job to create these videos full-time, calling himself, “The Hacksmith.”

Around the same time that Hobson got started on YouTube, a young British plumber named Colin Furze also began experimenting with the platform. Like Hobson, he began by posting videos of his hobbies (like BMX tricks) and silliness (like a stunt in which tried to serve food to moving cars).

Furze’s relationship with YouTube evolved when he began posting record breaking attempts. The first in this informal series was his effort to create the world’s largest bonfire. (“I collected pallets for over a year.”) He drew attention from British media when he supercharged a mobility scooter to drive more than seventy miles per hour. This led to a brief stint as a co-host of a maker show called “Gadget Geeks” that aired on the then fledgling Sky TV. After that traditional media experience, he scored a hit on YouTube by attaching a jet engine to the back of a bicycle. He decided to fully commit to making a living on his own videos.

I wrote about Hobson and Furze in my most recent essay for The New Yorker, which was titled, “A Lesson in Creativity and Capitalism from Two Zany YouTubers.” What drew my attention to these characters, and provided the main focus for my article, is what happened after they decided to make posting videos their full-time jobs.

Hobson adopted a standard strategy from the media industry: he tried to grow as fast as possible. He moved from his garage to a leased warehouse, and then, when that lease ran out, he took on a multi-million dollar mortgage to buy an even larger warehouse. He soon had thirty employees and around a quarter million dollars a month in overhead.

Furze, by contrast, stayed small. He continued to film his videos in his home workshop and a nearby old barn. He worked almost entirely on his own, with the exception of sometimes having his wife help hold a camera, or his friend Rick come lend a hand when some extra strength was needed. Furze’s overhead was reduced to more or less the cost of materials. Everything else he earns he keeps.

Hobson and Furze’s opposite strategies provide a neat natural experiment in the economics of this quirky corner of YouTube. What were the results? In 2024, Hobson’s channel published twenty-five beautifully produced videos that attracted more than twenty-seven million total views. In the same period, Furze launched five solo-produced videos on his main channel that attracted eighteen million views. He also, however, maintained a second channel with behind-the-scenes footage that pushes his total views for the year to forty-three million, nearly double Hobson’s results.

As I write:

“Furze’s solo success is a quirky challenge to the traditional narrative that survival requires continually growing, and that a small number of well-financed winners eventually eat most of the economic pie. He demonstrates that in certain corners of the creative economy an individual with minimal overhead can work on select attention-catching projects and earn a generous upper-middle-class income. Beyond this relatively modest scale of activity, however, the returns on additional investment rapidly diminish. As Hobson’s experience suggests, there’s no obvious path for a D.I.Y. video creator to turn his channel into a multimillion-dollar empire, even if he wants to. Furze seems to be maxing out the financial potential of his medium by staying small.”

In my article, I go on to the explore the specific reasons why small works so well in this medium (hint: it has to do with maintaining an authentic personal connection with your audience). But what I want to emphasize here is my broader conclusion. I think these particular corners of YouTube, along with some related creator-focused Internet-based technologies, including emails newsletter and podcasts, are helping to carve out space for a relatively broad “creative middle class.”

As social media continues to falter and stumble in its role as a unifying cultural force, its model of people volunteering their creative labor in return for uncompensated attention is beginning to lose its appeal. Colin Furze is one among many who are revealing an alternative engagement with the online world; one in which it’s possible for someone with sufficient talent to make a good living with minimal investment and maximal flexibility.

As I conclude in my piece, it’s still really hard to succeed in this new creative economy. But at least there’s space now to do so. As I write:

“In our era of consolidation and polarization, many online spaces can seem dreary, toxic, addicting, or some combination of the three. As my colleague Kyle Chayka wrote in 2023, most of the Web just ‘isn’t fun anymore.’ In Furze, however, I sensed some of the optimism of the early Internet.”

Sounds good to me.

#####

In Other News…

For nearly two decades, my friend Adam Gilbert (featured here in a 2007 Study Hacks post) has run My Body Tutor, an immensely successful health and fitness app that is based on the simple but powerful idea of using online coaches to hold people accountable.

His team just launched a new platform called DoneDaily that brings this same coach-driven accountability to professional productivity. I’m mentioning it here because DoneDaily deploys a lot of ideas I talk about here and in my books — including, notably, multi-scale planning — but now combined with a dedicated coach who you check in with daily to make sure your plan makes sense and that you’re taking action.

Anyway, I thought this was one of those ideas that makes so much sense that it’s surprising it didn’t exist before. Indeed, it’s the type of thing I might have built on my own if I didn’t already have a bunch of jobs. So I’m glad Adam got there first and was happy, at his request, to help share it. Check it out!

(Note: I have an affiliate relationship with this site.)

The post Lessons from YouTube’s Extreme Makers appeared first on Cal Newport.

What's Your Reaction?

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)