Forgotten Internet: UUCP

What’s Forgotten Internet? It is the story of parts of the Internet — or Internet precursors — that you might have forgotten about or maybe you missed out on them. …read more

What’s Forgotten Internet? It is the story of parts of the Internet — or Internet precursors — that you might have forgotten about or maybe you missed out on them. This time, we’re looking at Unix-to-Unix Copy, more commonly called UUCP. Developed in the late 1970s, UUCP was a solution for sending messages between systems that were not always connected together. It could also allow remote users to execute commands. By 1979, it was part of the 7th Edition of Unix.

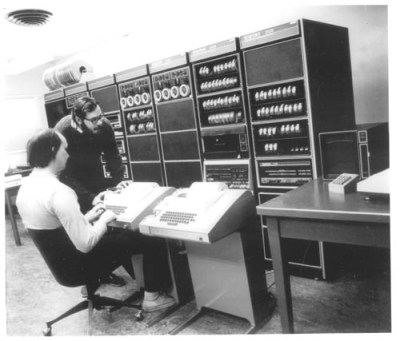

Operation was simple. Each computer in a UUCP network had a list of neighbor systems. Don’t forget, they weren’t connected, so instead of an IP address, each system had the other’s phone number to connect to a dial up modem. You also needed a login name and password. Almost certainly, by the way, those modems operated at 300 baud or less.

If a computer could dial out, when someone wanted to send something or do a remote execution, the UUCP system would call a neighboring computer. However, some systems couldn’t dial out, so it was also possible for a neighbor to call in and poll to see if there was anything you needed to do. Files would go from one system to another using a variety of protocols.

Under the Hood

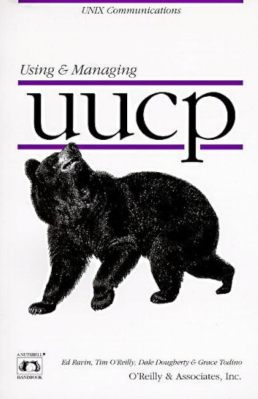

While UUCP was the name of the system (and UUCPNET the network of all computers reachable by UUCP), there were actually a few programs only one of which was named uucp. That program was the user’s interface to the system.

Other programs included uux for remote command execution, uucico which was the backend, and uustat which provided status information. Every hear of uuencode and uudecode? Those started here and were meant to convert binary to text and vice-versa, since you couldn’t be sure all the modems and computers could handle 8-bit data.

When uucico answers a call, it sends a Control+P along with a string indicating its host name. The caller responds with its own Control+P and host name, along with some options. If the caller isn’t recognized, the computer will hang up.

File Transfer

If the call continues, the caller can either send a file, request a file, send commands to execute, or ask for a hangup. Sending and receiving files or commands use g-protocol. Each packet was a Control+P, a number indicating packet size or type, a 16-bit checksum, the datatype, and a check digit for the header (the checksum didn’t cover the header).

The packet size was 1 to 8, corresponding to 32-4096 bytes. In practice, many small systems would only allow a value of 2, indicating 64 bytes. The size could also be 9 to indicate a control packet. There’s a lot of detail, but that’s the gist of it.

The g-protocol uses a sliding window system, which was innovative for its time and helpful, considering that systems often had long latencies between each other. In theory, a sender could have up to seven packets outstanding while sending data. In practice, many systems were fixed at a window size of three, which was not optimal for performance.

This led to the G-protocol (uppercase), which always used 4K packets with a window of three, and some implementations could do even better.

From the user’s perspective, you simply used the uucp command like the cp command but with a host name and exclamation point:

uucp enterprise!/usr/share/alist.txt alist.txt # copy alist.txt here from enterprise uucp request.txt starbase12!/usr/incoming/requests # copy request.txt to remote system starbase12.

You might also use uux to run a remote command and send it back to you. You could run local commands on remote files or vice versa using a similar syntax where ! is the local machine and kelvin! is a computer named kelvin that UUCP knows about.

Reading the Mail

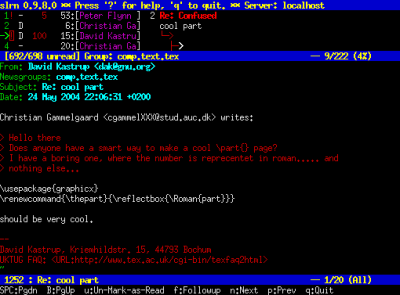

An important use of UUCP was early e-mail. Mail programs would cooperate with UUCP. UUCP E-mail addresses contain exclamation points (bangs) to identify the whole path to your machine. So, if you lived in New York and wanted to send an e-mail to Hackaday in California, it might require this address: NY4!east.node!center!west.node!CA8!Hackaday!alwilliams.

It was common, then, to provide your e-mail address relative to some “well-known” node like “…!west.node!CA8!Hackaday!alwilliams.” It was up to the sender to fill in the first part. Your mail would travel through each computer. There could easily be more than one path to …!Hackaday!alwilliams even from the same starting point and there would almost certainly be different paths from different starting hosts.

Usenet was also distributed this same way. Usenet deserves its own Forgotten Internet installment, but it was an early form of what we think of today as discussion groups.

Keep in mind that in both cases, UUCP didn’t know anything about machines more than one hop away. It was up to the mail program to understand that it was running on west.node and that it should then dial up the CA8 computer and transmit the message to it.

Versions

[Mike Lesk] at Bell Labs originally developed the code, and by 1978, there was a UUCP network of 82 Unix machines internal to Bell Labs. Around 1983, there was an AT&T rewrite known as HoneyDanBer UUCP, referencing the authors’ names, that fixed some bugs.

Then [Ian Lance Taylor] wrote a GPL version in 1991, often known as Taylor UUCP. It was flexible and could communicate with other versions of UUCP. It could also go faster when talking to another Taylor UUCP instance.

There were UUCP programs for MSDOS, CP/M, Mac OS, and VMS. Probably even more than that. It was a very popular program.

All Good Things

Of course, full-time connections to the Internet would be the beginning of the end for UUCP. Sure, you could use UUCP over a network connection instead of a dial-up modem, but why? Of course, your phone bill would definitely go down, but why use UUCP at all if you can just connect to the remote host?

In 2012, a Dutch Internet provider stopped offering UUCP to the 13 users it had left on the service. They claimed that they were likely the last surviving part of the UUCP world at that time.

Of course, you can grab your modem and set up your own UUCP setup like [Chartreuse Kitsune] did recently in the video below.

Times were different before the Internet. It is amazing that over a single lifetime, we’ve gone from 300 baud modems to over 1 petabit per second.

What's Your Reaction?

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)