A Plea for Heroic Poets

History reminds us that the viciousness of authoritarianism only strengthens the artist’s hand.

Our fractured age’s greatest heroes are a far cry from Achilles. They fight not for glory but freedom, with weapons forged of pure moral steel. Consider the fatalistic courage of the late Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny. By the time he was poisoned in 2020 with a neurotoxin secretly applied to his underpants by Vladimir Putin’s agents, he’d suffered at least one previous chemical attack and been jailed by the regime more than 10 times. After five months of convalescence in Germany, Navalny returned to Moscow, where he was arrested at the airport and later imprisoned in a remote penal colony. He seemed undaunted by the prospect of death. “If they decide to kill me,” he said in the 2022 documentary film Navalny, “it means that we are incredibly strong.”

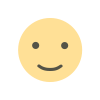

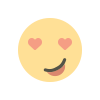

The supreme Soviet poet Osip Mandelstam, who fell afoul of the Bolsheviks shortly after the Russian Revolution of 1917, was Navalny’s equal in staking his life on publicly resisting ideological tyranny. Mandelstam sealed his fate in late 1933, when he composed verse that portrayed Stalin as a murderer with “cockroach whiskers” who “forges order after order like horseshoes, / hurling them at the groin, the forehead, the brow, the eye.” Brutally interrogated in Moscow’s Lubyanka prison in 1934, he was sent into exile, was rearrested in the spring of 1938, and died in a Gulag transit facility that winter.

In her memoir of those terrible years, Hope Against Hope, his wife, Nadezhda—whose name means “hope,” and who published a sequel, Hope Abandoned—writes that Mandelstam’s “destiny was hatched from character, like a butterfly from its chrysalis.” He attacked Stalin because he “did not want to die without stating in unambiguous terms what he thought was going on around us.” Mandelstam anticipated Navalny when he observed that “poetry is power” and is “respected only in this country—people are killed for it.” Both men died in Siberian prison camps at the age of 47—86 years apart.

[Read: A dissident is built different]

The power of Mandelstam’s poetry, a bell pealing in the muffle of a pea-soup fog, arises from the harmony of his words and actions. “The dominant theme in the whole of M.’s life and work,” Nadezhda writes, “was his insistence on the poet’s dignity, his position in society and his right to make himself heard.” Mandelstam’s speech was his deed. In 1918, he saved the life of an art historian targeted by the Cheka (the secret police), ignoring a pistol-brandishing Chekist’s warning that he’d be shot if he dared to interfere in the case. He later stopped the execution of five bank officials by sending to Nikolai Bukharin a volume of poems that the Central Committee member had helped him publish, accompanied by the message that “every line here is against what you are going to do.” Bukharin returned the favor by writing to Stalin in Mandelstam’s defense after his arrest in 1934. It’s hard to say what he appreciated more: Mandelstam’s adamant integrity or his poetry. While terrified artists mouthed the alien language of the state, Mandelstam’s verse sprang inexorably from some high and sacred ground that would not fall. He captures this almost physical necessity in his very short poem “Meteorite,” which describes an “exiled line” of poetry that, having fallen “from the heavens” and woken the earth, “couldn’t be anything else.”

It’s not that Soviet leaders disliked Mandelstam’s work. Genrikh Yagoda, the head of the secret police who, along with Bukharin, was condemned to death in the last show trial of old Bolsheviks in 1938, was so fond of Mandelstam’s Stalin poem that he learned it by heart. Nor, it seems, were leaders particularly hostile to him because he was a Jew: Official anti-Semitism in Stalin’s Russia didn’t hit full swing until 1952, when all of the prominent Yiddish writers and eight other Jews were executed on Stalin’s orders in what came to be known as the Night of the Murdered Poets. According to Nadezhda, Mandelstam’s real crime was his defiant confidence, his “usurpation of the right to words and thoughts that the ruling powers reserved exclusively to themselves.” Equally unforgivable was his inclination to “lay down the law, as a writer is supposed to”—that is, to pass unequivocal judgment on social realities, a consequence of his inability to “be indifferent to good and evil, and … [to] say that all that exists is rational” (a Communist dogma frequently invoked to excuse terror as historical necessity).

The viciousness of the totalitarian state only strengthened the poet’s hand. For while rulers who rely on terror lack authority—power that is rooted neither in coercion nor persuasion but is spontaneously recognized as legitimate, like that of a doctor on an airplane when a passenger falls ill—Mandelstam radiated it. This was not just because he was a generous and conscientious man who couldn’t keep a second pair of trousers (there was always someone more in need), and who blamed himself for leading into temptation whatever friend betrayed him after he recited his Stalin poem to a dozen people. His authority came from what Nadezhda calls “the absolute character” of his urge to be a source of truth for his fellow men, and his inability “to curb or silence himself by ‘stepping on the throat’ of his own song.” Above all, it came from the authenticity of his “inner voice.”

But what awakens that voice? For Mandelstam, poetry sprang from joy as much as from anger—and emerged in the manner that a musical phrase does. Like the Irish poet W. B. Yeats, Mandelstam composed by ear, uttering the same lines with minor variations over and over until they achieved their proper form. Watching him work must have been like listening to a songbird, one whose protective coloring couldn’t conceal its deepest feelings. Mandelstam, who called poetry the “yeast of the world,” suggests as much in his poem “The Cage”:

When the goldfinch like rising dough

suddenly moves, as a heart throbs,

anger peppers its clever cloak

and its nightcap blackens with rage.

The goldfish sings in a cage built from “a hundred bars of lies” and the plank on which he sings is “slanderous.” These are inhospitable conditions, but Nadezhda explains that he was reconciled with persecution and poverty by his “simple love of life.” For him, eternity was “tangibly present in every fleeting fraction of time, which he would gladly stop and thus make even more tangible.” He knew, in the words of the poet Anna Akhmatova, “from what trash poetry, quite unashamed, can grow,” turning into vibrant song the colorless prose of daily existence under the crushing weight of totalitarianism. This was the “drop of good” that “the merciless grip of the age” squeezed out of him. But the evil age could not forgive him for that good, and not just him: the feeling for poetry, which Mandelstam regarded as the definitive characteristic of the true intelligentsia, “went with the qualities of the mind which in our country doomed people to death.” Foremost among them was the dynamic strength of the individual who sings his inner freedom, as Mandelstam does in a 1935 poem that ends with the triumph of the poetic voice: “you could not stop my lips from moving.”

Courageous and authoritative individual voices are as urgently necessary today as they have ever been, not just in Russia but across the West. In Soviet fashion, the proponents of cultural Marxism seek consensus through intimidation, insisting, among other things, that “oppressors” have no right to an opinion about “oppressed” groups or individuals. Primary and secondary schools have for years spoon-fed students such ideological pap, damaging their capacity to appreciate any ideas not packaged in hackneyed phrases. In universities, professors expose intellectually susceptible undergraduates to popular partisan concepts, concepts as stale, in Orwell’s words, as “tea leaves blocking a sink.” These viral variants of recombinant Marxism—having in common a peculiarly enervated voice—have now spread throughout society by multiple vectors, including ubiquitous DEI training programs, to which 52 percent of U.S. workers have now been subjected. One new study suggests that these programs “increase the endorsement of the type of demonization and scapegoating characteristic of authoritarianism.”

[Read: Poetry is an act of hope]

Donald Trump’s reelection, among other cultural shifts, suggests that Americans have grown tired of progressive bullying. But if anything, technology poses a more insidious threat to the development of future Mandelstams than ideology. It’s not just that people prefer new iPhones to old books. I tell undergraduates who are laboring to improve their writing that their ultimate goal is the achievement of style: a voice so distinctive that readers will immediately recognize whose work they hold in their hands. But nearly four in 10 students admit to using programs such as ChatGPT to write their papers, and the actual rate of AI plagiarism is probably much higher. As this technology advances, few will be able to resist the temptation to outsource the greatest part of their thinking to machines.

This brings to mind the poets of ideology and algorithms that Nadezhda would have called “mechanical nightingales.” When a friend told the Mandelstams about a bird he’d seen that, on its owner’s signal, hopped out of its cage, sang, and then obediently returned to confinement, his precocious son remarked: “Just like a member of the Union of Writers.”

Too many writers and artists in the West sing the same potted tunes on demand, hopping from perch to scandalous plank. But unlike songbirds, poets and readers can learn from the dead, and they can refuse to be tamed by the forces of ideological conformity and technological brain-suck. That’s the spirit we need today. Let a hundred poets whose lips are still moving, heroes living or dead, leaven our days, and let them teach their life-affirming music to our young.

What's Your Reaction?

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)